1. Evolution of Realism in IR

2. Core Assumptions of Realism

3. Classical Realism

3.1. Political Realism

3.1.1.1. Ε.Η.Carr and Realism

3.1.2. 2.Morgenthau and Realism

4. Neorealism

4.1. Structural Realism

4.1.1. 1. Defensive Realism

4.1.2. 2. Offensive Realism

5. Neoclassical Realism

5.1 Schelling and Strategic Realism

6. Criticism

7. Conclusion

Hey champs! you’re in the right place. I know how overwhelming exams can feel—books piling up, last-minute panic, and everything seems messy. I’ve been there too, coming from the same college and background as you, so I completely understand how stressful this time can be.

That’s why I joined Examopedia—to help solve the common problems students face and provide content that’s clear, reliable, and easy to understand. Here, you’ll find notes, examples, scholars, and free flashcards which are updated & revised to make your prep smoother and less stressful.

You’re not alone in this journey, and your feedback helps us improve every day at Examopedia.

Forever grateful ♥

Janvi Singhi

Give Your Feedback!!

Topic – Realism Approach (Notes)

Subject – Political Science

(International Relations)

Table of Contents

Evolution of Realism in IR

- The story of Realism begins with the inter-war period (1919–39), when idealists/utopian writers focused on understanding the causes of war to prevent it.

- Realists criticized the idealists for ignoring power, overestimating human rationality, assuming shared national interests, and being overly optimistic about avoiding war.

- The outbreak of the Second World War (1939) confirmed the inadequacy of the idealist approach, leading to the rise of Realism.

- A new approach, based on the timeless insights of Realism, replaced the discredited idealist approach.

- Histories of International Relations describe a Great Debate in the late 1930s and early 1940s between inter-war idealists and a new generation of realist writers, including E. H. Carr, Hans J. Morgenthau, and Reinhold Niebuhr, who emphasized the ubiquity of power and the competitive nature of politics among nations.

- The standard account is that realists emerged victorious, and much of the subsequent development in International Relations is, in many respects, a footnote to Realism.

- Initially, Realism needed to define itself against the alleged ‘idealist’ position.

- From 1939 to the present, leading theorists and policy-makers have continued to view the world through realist lenses, focusing on interests rather than ideology, seeking peace through strength, and recognizing that great powers can coexist even with antithetical values and beliefs.

- Realism offers a ‘manual’ for maximizing the interests of the state in a hostile environment, explaining its dominance in the study of world politics and why alternative perspectives must engage with and attempt to go beyond it.

- Post-World War II, Realism influenced American leaders, teaching them to focus on interests over ideology, peace through strength, and coexistence of great powers despite conflicting values.

- The theory of Realism after the Second World War rests on a classical tradition of thought, tracing back to figures like Thucydides, Niccolo Machiavelli, Thomas Hobbes, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

- These thinkers, associated with raison d’état (reason of state), provide maxims to leaders on conducting foreign affairs to ensure the security of the state.

- Historian Friedrich Meinecke defines raison d’état as the fundamental principle of international conduct, instructing statesmen to preserve the health and strength of the state.

- The state, as the key actor, must pursue power, and state survival requires rational calculation of actions in a hostile environment.

- Realists assert that state survival can never be guaranteed, and the use of force, including war, is a legitimate instrument of statecraft.

- The assumption that the state is the principal actor and that the international environment is perilous defines the essential core of Realism.

- Classical and modern realists are concerned with the role of morals and ethics in international politics, remaining skeptical of universal moral principles.

- Realists warn state leaders against sacrificing self-interest for indeterminate ethical conduct, emphasizing that survival requires distancing from traditional morality, which values caution, piety, and the greater good.

- Machiavelli argued that adhering to traditional principles could be harmful for state leaders; instead, leaders must follow a morality of political necessity and prudence.

- Raison d’état suggests a dual moral standard: one for individual citizens and a different one for the state in external relations, justifying acts like cheating, lying, or killing that would be unacceptable domestically.

- Realists contend that the state itself represents a moral force, as it enables the ethical political community domestically; thus, preserving the state becomes a moral duty.

- There is a significant continuity between classical realism and modern variants, with three core elements—statism, survival, and self-help—present in both Thucydides and Kenneth Waltz.

- Realism identifies the group as the fundamental unit of political analysis. Historically, it was the polis or city-state, but since the Peace of Westphalia (1648), the sovereign state is the principal actor.

- The state-centric assumption of Realism emphasizes the state as the legitimate representative of the collective will, enabling it to exercise authority domestically, while the international arena is characterized by anarchy, meaning the absence of a central authority.

- Realists draw a sharp distinction between domestic and international politics, highlighting that international politics is a struggle for power with outcomes qualitatively different from domestic politics.

- The structure of international politics is anarchic, with sovereign states as the highest authority, whereas domestic politics is hierarchical.

- Under anarchy, the first priority for leaders is to ensure state survival, as it cannot be guaranteed; historical examples, such as Poland, illustrate the consequences of failing to survive.

- Power is crucial, traditionally defined in military strategic terms, and the promotion of national interest is an iron law of necessity for all states.

- Self-help is central in an anarchic system, where each state is responsible for its own security and well-being, without relying on other states or international institutions like the UN.

- States can augment power capabilities, for instance through a military build-up, but smaller states may need to use the balance of power mechanism, forming alliances to preserve independence.

- The balance of power seeks an equilibrium, preventing domination by any single state or coalition; the Cold War alliances of NATO and the Warsaw Pact exemplify this mechanism.

- The peaceful conclusion of the Cold War surprised many realists, highlighting the limits of realist predictions in accounting for developments like regional integration, humanitarian intervention, and the rise of non-state actors.

- Critics argue that Realism fails to explain intra-state wars, regional integration, security communities, and the decline of the state relative to transnational actors.

- Despite criticisms, Realism resurged in the 1980s as structural realism (neo-realism), demonstrating its resilience and the claim that its laws of international politics remain true across time and space.

- Realists maintain that political conditions may change, but the world continues to operate according to the logic of Realism.

- Realist IR theory is valid at all times, as the basic facts of world politics never change, according to most realists.

- There is an important distinction between classical realism and social science realism.

- Classical realism is a ‘traditional’ approach to IR, normative, and focuses on core political values: national security and state survival.

- Classical realist thought has been evident in many historical periods, from ancient Greece to the present.

- Strategic and structural realism is largely a scientific approach, mostly American in origin, and has been the most prominent IR theory in the United States, home to the largest number of IR scholars in the world.

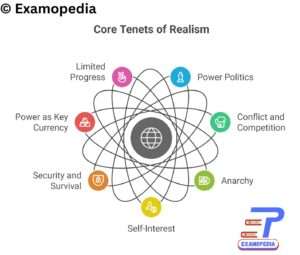

Core Assumptions of Realism

According to Peu Ghosh, the basic assumptions of Realism are:

-

- The international system is anarchic, with no central authority or world government above states.

- Sovereign states are the principal actors in international politics.

- States act as rational and unitary actors, guided primarily by their own national interests.

- National security and survival are the primary national interests of every state.

- To ensure their security, states strive to increase power—the ultimate means of survival.

- Power and capabilities determine the relations among states and shape the global order.

- National interest, defined in terms of national power, guides every action of the state in international relations.

- Realism begins with a pessimistic view of human nature. Human beings are self-interested, competitive, and driven by a desire to dominate others. This tendency is universal, as all humans seek advantage and fear subordination. Hans Morgenthau described this as the “will to power,” stating that “Politics is a struggle for power over men… power is its immediate goal.” Thinkers like Thucydides, Machiavelli, and Hobbes shared this belief that politics—especially international politics—is rooted in the struggle for power.

- Because of this human condition, the international system is anarchic, meaning no higher authority exists above states. Each state must rely on self-help for survival, creating a conflictual environment where states compete for power and security in a world filled with uncertainty.

- The state is the central and sovereign actor in this anarchic world. While all states are formally equal, in practice power is unevenly distributed, leading to a hierarchy dominated by great powers. Other actors—such as individuals, IGOs, NGOs, and MNCs—play only secondary roles in shaping international politics.

- The national interest and survival of the state are the fundamental goals of foreign policy. The raison d’état (reason of state) justifies any action necessary for national security, even if it violates moral or legal norms. As Hobbes argued, without strong state authority, life would be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

- Power is the central concept in Realism. Politics and power are inseparable—“all politics is power politics.” States seek power not merely to expand but primarily to secure themselves and deter threats in an anarchic world. Power is both relative (measured against others) and relational (dependent on interactions).

- Since no global authority guarantees safety, states operate in a self-help system. This results in the security dilemma, where one state’s attempt to increase its security (e.g., military buildup) makes others feel insecure, prompting an arms race or conflict escalation.

- Given human nature, anarchy, and competition for power, conflict and war are inevitable features of international politics. War is viewed as a legitimate instrument for resolving disputes. Peace is temporary and fragile, maintained only through balance of power or deterrence.

- Realists are skeptical of international morality, law, and institutions. States comply with treaties or norms only when they align with their interests. There are no binding moral obligations between sovereign states. As Machiavelli argued in The Prince, the true duty of a ruler is not moral virtue but the preservation and advancement of the state.

- Realists reject the liberal notion of progress in international politics. Since human nature and anarchy remain constant, rivalry, conflict, and war persist throughout history. Hence, history follows a cyclical pattern, not a progressive one.

- The normative core of Realism lies in the responsibility of leaders to ensure the security and survival of their states. This duty overrides moral or legal considerations, prioritizing national interest, territorial integrity, and the preservation of a distinct way of life over universal ideals.

- To sum up, Realism portrays international politics as an arena of power, conflict, and competition among self-interested states, operating in an anarchic system, where security and survival are the ultimate goals, power is the key currency, and progress is limited by unchanging human nature.

International Relations Membership Required

You must be a International Relations member to access this content.