1. Evolution of Marxism in IR

2. Basic Assumptions of Marxist Approach

3. Traditions of Marxism

4. Marx Internationalized: from Imperialism to World System Theory

5. World System Theory

5.1. 1.Immanuel Wallerstein

5.1.1. Key features:

5.1.2. Dependency Theory

5.2. 2. Johan Galtung and His Structural Theory of Imperialism

6. Neo-Marxism

6.1. 1. Gramscianism

6.1.1. Robert Cox analysis of World Order

6.2. 2. Critical Theory

6.3. 1. Herbert Marcuse concept of One Dimensional Man

6.4. 2. Habermas on Legitimation Crisis

6.5. Critical Security Studies

7. Marxist View of State in IR

7.1. 1.Instrumentalist Marxism

7.2. 2.Structuralist Marxism

8. Post-Marxism/New Marxism

9. Evaluation

10. Conclusion

Hey champs! you’re in the right place. I know how overwhelming exams can feel—books piling up, last-minute panic, and everything seems messy. I’ve been there too, coming from the same college and background as you, so I completely understand how stressful this time can be.

That’s why I joined Examopedia—to help solve the common problems students face and provide content that’s clear, reliable, and easy to understand. Here, you’ll find notes, examples, scholars, and free flashcards which are updated & revised to make your prep smoother and less stressful.

You’re not alone in this journey, and your feedback helps us improve every day at Examopedia.

Forever grateful ♥

Janvi Singhi

Give Your Feedback!!

Topic – Marxism Approach (Notes)

Subject – Political Science

(International Relations)

Table of Contents

Evolution of Marxism in IR

- Marxism entered International Relations as a critique of mainstream theories like Realism and Liberalism, which were seen as ignoring the economic foundations of world politics.

- Its roots lie in Karl Marx’s analysis of capitalism, especially the idea that economic structures determine political and social relations, including those between states.

- Class struggle, a central Marxist concept, was extended to the international level—interpreting global politics as shaped by relations between the capitalist core and the exploited periphery.

- Marxism’s inclusion in IR was influenced by post-1945 debates on development, imperialism, and dependency, as scholars began to apply Marxist ideas to North–South inequalities.

- The Cold War context further popularized Marxist perspectives, as the Soviet Union’s ideology positioned Marxism as a rival framework for understanding global order.

- However, Marxist theory has struggled to establish a strong foothold in International Relations (IR).

- Most Marxist discussion in IR has been narrowly focused on imperialism and tends toward one-sided interpretations of international phenomena.

- Its emphasis on economic factors has not fully explained political, ideological, and security issues, which are core concerns of IR.

- Consequently, Marxism has faced difficulty in carving a niche among mainstream IR theories.

- Karl Marx did not develop a dedicated theory of international relations, but his works with Engels—such as the Communist Manifesto (1848) and Das Capital (1867)—contain references to:

- Wars and conflict

- Proletarian internationalism

- World revolution

- Global expansion of capitalism leading to revolutionary socio-economic transformation

- Later thinkers like Lenin, Stalin, Mao, and other communist scholars adapted and expanded Marx’s ideas to explain contemporary international events in the light of changing historical and global contexts.

- These adaptations reflect an effort to use Marxist principles to interpret the dynamics of world politics, even though a comprehensive Marxist IR theory remained elusive.

- In the 1960s and 1970s, Marxism became formally recognized in IR through the rise of critical and neo-Marxist schools, which questioned the state-centric and power-politics assumptions of Realism.

- These scholars emphasized the role of economic exploitation, global class relations, and structural dependency in shaping international outcomes.

- The entry of Marxism into IR thus marked a shift from political and military analyses to economic and structural explanations of world order.

- With the end of the Cold War and the global triumph of free-market capitalism, it was widely believed that Marxism had reached its end and could be relegated to the dustbin of history.

- The collapse of the Soviet Union and the failure of the so-called “great experiment” were seen as proof that Marxist ideas led to a historical dead end, while liberal capitalism was heralded as the inevitable future.

- Although Communist parties continued to rule in China, Vietnam, and Cuba, they no longer posed a challenge to global capitalist hegemony. In fact, these regimes themselves began to adopt market-oriented reforms, mimicking many of the core features of capitalist societies to sustain their political legitimacy.

- Despite this apparent demise, Marxist thought has refused to disappear. Instead, it has experienced a renaissance in recent decades, driven primarily by two major developments.

- First, the collapse of the Soviet bloc freed Marxism from its association with the failures of Marxism-Leninism. The oppressive nature of Stalinism and the authoritarianism of Soviet regimes had discredited Marxism as a liberating philosophy. The end of the USSR thus allowed a re-evaluation of Marx’s ideas independent of the practices of those states that had claimed to represent him.

- This “clean slate” made it possible to appreciate Marx’s work without defending the vanguard party, democratic centralism, or command economies—concepts which do not actually appear in Marx’s original writings but were later distortions by Leninist state ideologies.

- Second, Marx’s theoretical analysis of capitalism continues to hold immense explanatory power. His insights into capitalism as a mode of production, its internal contradictions, and its crisis tendencies remain remarkably relevant in the 21st century.

- The penetration of market logic into all spheres of life has only confirmed Marx’s claim that capitalism is both dynamic and inherently unstable. Events like the 1987 stock-market crash and the Asian financial crisis of the 1990s illustrate the recurring crises that Marx identified as structural features of capitalism itself.

- While liberal theorists maintain that markets naturally tend toward equilibrium and stability, Marx argued that crises are inevitable outcomes of capitalist contradictions—particularly the tension between capital accumulation and social inequality.

- In the field of international relations, Marxism offers a distinct and deeper perspective compared to Realism and Liberalism. Whereas these mainstream theories focus on states, power, and institutions, Marxism seeks to uncover the underlying structures of the global capitalist system that shape and constrain state behavior.

- For Marxists, world events—wars, treaties, aid operations—are not isolated acts of statecraft but manifestations of capitalist power relations and the imperatives of global production and profit.

- This analysis is discomforting because it exposes how global capitalism perpetuates inequality, ensuring that wealth and power remain concentrated among a few while the majority remain impoverished and exploited.

- Marx’s famous dictum captures this reality: “Accumulation of wealth at one pole is, therefore, at the same time accumulation of misery, agony of toil, slavery, ignorance, brutality at the opposite pole.”

- Hence, the revival of Marxist thought stems from its continued analytical relevance in explaining crises, inequalities, and power hierarchies in the modern capitalist world—phenomena that mainstream theories fail to address adequately.

- The study of historical materialism and its contemporary offshoots thus remains vital for understanding the hidden structures and contradictions of global politics.

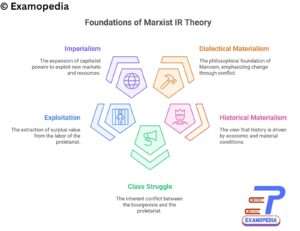

Basic Assumptions of Marxist Approach

The Marxist theory in International Relations would be difficult to understand without a basic idea of Marxism. Broadly speaking, the writings of Karl Marx and his friend Frederick Engels constitute the basic premises of Marxism. Later on, the views of socialist leaders like Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, Mao Zhe Dong and several academicians and scholars were added to the Marxist political philosophy. The neo-Marxists have also added fresh dimensions to Marxist ideology to make it academically more rich, time-worthy, and relevant in today’s world. The following are a few basic tenets of Marxist political philosophy, as developed by Marx and Engels:

- All these theorists share with Marx the view that the social world should be analyzed as a totality. The division of the social world into history, philosophy, economics, political science, sociology, international relations, etc., is arbitrary and unhelpful.

- Economic or materialistic determination provides a clue to understand international relations.

- The Marxist idea of dialectical materialism holds the view that change is inevitable in nature and in society, and changes must be qualitative rather than merely quantitative.

- The Marxist view of historical materialism argues that in all hitherto existing societies (except primitive communism) there were class divisions among people based on their relations to property and means of production; and changes always took place through class struggles (clash of interests of opposing classes).

- Classes are mainly economic groupings of people based on their relation to the production process in the society. Thus, those who own the means of production belong to one class, and those who do not own belong to another class.

- Although class divisions existed in all societies except in case of primitive communism, antagonism among classes reached its peak in the capitalist society, which ultimately was divided into two classes: the capitalists (the owning class) and the proletariat (the non-owning class).

- Excessive production and profit motive of the capitalists led to severe exploitation of the proletariat in the capitalist society. Unable to bear such extreme exploitation, the proletariat consolidates as a class on the basis of economic, political, and ideological similarities, and wages a class struggle against the capitalists. In this class struggle, the proletariat wins and establishes, gradually, the socialist society which is free of classes and class divisions.

- The state was created by the owning class to safeguard its interests and to oppress the non-owning class through different mechanisms, such as the police. Therefore, the state, in Marxist view, served the interests of the owning class and became a tool for oppression. When class division ends in the socialist society, the state will have no role to play in the society, and therefore, will ‘wither away’.

- Proletariats all over the world are exploited, and therefore share common interests. They are not bound by national borders or national interests, because their agony everywhere in the world is the same—they are exploited to the tilt by the capitalists. The proletarian revolution is, therefore, international in character.

- Economic issues in the society constitute the base in Marxist political philosophy; every other aspect, such as politics, culture, education, or religion, remain at the super-structural level, dependent on economic factors (the base).

- Marx did not advocate that analysts remain detached or neutral; he emphasized that “philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point, however, is to change it.”

- He was committed to emancipation and sought to develop understanding to overthrow the prevailing order and replace it with a communist society, in which wage labour and private property are abolished and social relations transformed.

Professor Arun Bose provides insights into the Marxist view of international politics. According to him, the basic framework of international politics includes four basic tenets.

- Proletarian Internationalism: The essence of proletarian internationalism is contained in the Communist Manifesto, which ends with the call: “workers of the world unite”. The ideal of proletarian revolution includes:

- The word proletariat has a common interest, independent of all nationality.

- Working men have no country since the proletariat of each country must first acquire political supremacy and constitute itself as a nation; it is itself national.

- United action by the proletariat is one of the first conditions for the emancipation of the proletariat.

- In proportion, as the exploitation of one individual by another is put to an end, similarly, the exploitation of one nation by another will also be put to an end, and thus, hostility of one nation by another will come to an end.

- The word proletariat has a common interest, independent of all nationality.

International Relations Membership Required

You must be a International Relations member to access this content.