Detailed Notes

1. Belan Valley

2. Son Valley

3. Mesolithic – Vindhya Region

4. Mesolithic Ganga Plains

5. Neolithic Culture – South India

6. Neolithic Culture – Vindhyas

7. Neolithic Culture – Ganga Plains

8. Ahar Culture

9. Kayatha Culture

10. Malwa Culture

11. Jorwe Culture

12. Ochre Colored Pottery Culture (OCP)

13. Painted Grey Ware Culture

14. Iron Age: Antiquity of Iron

15. Antiquity of Iron

16. Painted Grey Ware Culture

17. Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) Culture

18. Atranjikhera

19. Hastinapur

20. Kaushambi

21. Taxila

22. Arikamedu

When I began my college journey, I often felt lost. Notes were scattered, the internet was overflowing with content, yet nothing truly matched the needs of university exams. I remember the frustration of not knowing what to study, or even where to begin.

That struggle inspired me to create Examopedia—because students deserve clarity, structure, and reliable notes tailored to their exams.

Our vision is simple: to make learning accessible, reliable, and stress-free, so no student has to face the same confusion I once did. Here, we turn complex theories into easy, exam-ready notes, examples, scholars, and flashcards—all in one place.

Built by students, for students, Examopedia grows with your feedback. Because this isn’t just a platform—it’s a promise that you’ll never feel alone in your exam journey.

— Founder, Examopedia

Always Yours ♥!

Harshit Sharma

Give Your Feedback!!

Topic – Important Prehistoric Regions and Culture (Notes)

Subject – History

(Ancient Indian History)

Table of Contents

Belan Valley

Introduction and Geography:

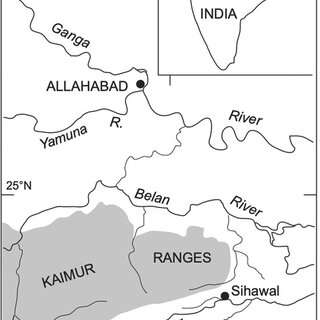

The Belan Valley is located in the eastern part of the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, along the course of the Belan River (a tributary of the Tons, which in turn joins the Ganga). The valley lies in the northern fringes of the Vindhyan plateau region, covering parts of the districts of Sonbhadra, Mirzapur, and Prayagraj (formerly Allahabad) in Uttar Pradesh.

The geography of the valley is significant: the river provided a perennial water-supply, the alluvial terraces and nearby upland raw-material zones offered excellent conditions for human settlement, tool-making and subsistence. The valley’s physical setting made it possible for continuous human habitation and allowed archaeologists to record a remarkably long sequence of prehistoric cultural phases.

One of the most striking features of the Belan Valley is its long and nearly continuous sequence of prehistoric human occupation, from Palaeolithic times through the Mesolithic and Neolithic, and into the Chalcolithic/early metal-use phases.

Palaeolithic Period:

In the valley, archaeological and geomorphological studies have identified deposits associated with the Lower, Middle and Upper Palaeolithic stages. For example, studies show alluvial gravels dated to ~85 to ~72 thousand years before present (ka BP) underlying later Mesolithic and Neolithic strata in the valley. These sediments suggest that early hominins or early humans were operating in this region during Marine Isotope Stage 5 or earlier.

Stone-tool assemblages of quartzite and other local stones have been found. The valley thus plays a role in our understanding of early technology and environment in north-central India.

Mesolithic Period:

Following the Palaeolithic phases, the valley sees evidence of a Mesolithic culture characterised by microlithic tool-kits (small flaked stone tools such as crescents, triangles, lunates) and semi-sedentary or seasonal occupations. At sites like Chopani Mando in the Belan Valley, excavations revealed microliths, hearth-features, and evidence of food-gathering, fishing and hunting activities.

Neolithic Period:

The Neolithic phase in the Belan Valley is especially important because it shows the shift to domestication of plants and animals, permanent settlement, pottery manufacture, and more complex social organisation. For example, at the site Mahagara excavations revealed a village plan including a cattle-pen, domesticated animal bones (cattle, sheep/goat), pottery, and what has been interpreted as early rice cultivation. Similarly, at Koldihwa (in the Belan Valley) there is evidence of early rice (Oryza sativa) cultivation and domestication of animals.

Chalcolithic / Early Metal Use:

Beyond the Neolithic, though less extensively studied in comparison, the valley shows traces of early metal usage (copper) and craft specialisation, alongside continuing settlement dynamics. The literature points to this phase though it is not as rich in detailed discussion as earlier Neolithic evidence.

Key Sites and Their Significance:

Several excavated and surveyed sites in the Belan Valley are crucial for reconstructing its prehistoric sequence:

- Chopani Mando: Located on the banks of the Belan River, about 77 km from Prayagraj, this site was excavated in 1967 and 1977-78. It yields a three-phase sequence (Palaeolithic → Mesolithic → Neolithic) with circular/oval settlement plans, microliths, pottery, and early rice remains dating to around 7000-6000 BCE.

- Mahagara: A Neolithic settlement in the Belan Valley showing house structures, a cattle-pen, rounded celts, microliths, bone tools, pottery (cord-impressed, rusticated, burnished wares), and early rice and domesticated animal remains.

- Koldihwa: This site is important for the evidence of early rice cultivation in the Ganga plains region. The site lies in the Belan Valley near Devghat.

- Numerous other Mesolithic open-air and rock-shelter sites in the valley enhance the richness of the record. The valley reportedly has over 100 Mesolithic sites identified.

Subsistence, Technology and Environment:

The Belan Valley offers a detailed record of how prehistoric human societies adapted to environmental and climatic changes, shifted subsistence patterns, and evolved technologically.

- In the earliest phases humans hunted, gathered and scavenged wild resources, making large, crude stone tools for cutting, chopping etc.

- In the Mesolithic phase the appearance of microlithic tools suggests more refined hunting/gathering technology, possibly small game hunting, fishing and plant-gathering.

- With Neolithic transitions we see domestication of animals (cattle, sheep/goat), cultivation of cereals (especially rice) and the making of permanent villages, pottery manufacture, and potentially early craft specialisation. The Belan Valley thus marks the shift from nomadic or semi-nomadic to settled agricultural life.

- Environmental studies (geomorphology and alluvial stratigraphy) show that the valley underwent climatic and fluvial changes. For example, analysis of strata in the valley shows fluvial activity, inter-bedded with wind-blown silt, indicating climatic fluctuations in the late Pleistocene to early Holocene.

- The technological progression is clear: stone-axes and choppers (Lower/ Middle Palaeolithic) → microliths (Mesolithic) → pottery, celts, querns, domesticated animal bones (Neolithic) → early metal (Chalcolithic).

- Plant remains (especially rice) from sites like Koldihwa and Mahagara place the Belan Valley among the earliest contexts for rice cultivation in the Ganga plains.

Cultural and Archaeological Importance:

The Belan Valley is often described as a “prehistoric textbook” of northern India because it preserves a near-continuous sequence of cultural phases in a single region. The valley’s importance lies in several key aspects:

- It furnishes a long time-span of human occupation, allowing scholars to study cultural continuity and change (tools, settlement, subsistence) in one geographical setting.

- The stratigraphy is relatively well preserved, enabling reconstruction of how human societies responded to climatic, environmental and riverine changes.

- It contains evidence of early agriculture (especially rice), making it relevant to understanding the origins of farming in north-central India.

- The valley bridges the gap between upland (Vindhyan) zones and the Gangetic plains, offering insights into how prehistoric communities spread and settled in the larger Ganga basin.

- The material culture (stone-tools, pottery, domesticated animal remains, plant remains) helps chart technological and social evolution from the early Stone Age to more complex Neolithic societies.

Challenges and Current Research:

Despite its rich heritage, the Belan Valley also faces challenges and continuing research needs:

- The precise dating of some early agricultural evidence (especially rice) is debated. For example, the early dates (~7000 BCE) for rice at Koldihwa have been questioned, with later re-examinations suggesting Neolithic occupation mainly after ca. 1900 BCE.

- Fluvial dynamics (river erosion, sediment re-working) complicate the stratigraphic interpretation of artefact layers, requiring careful geomorphic and dating work.

- Natural processes (erosion, river meanders) and modern land use change threaten some of the open-air prehistoric sites, and excavation/ preservation is resource-intensive.

- More detailed publication and comparative studies remain to be done to integrate Belan Valley evidence with other prehistoric regions of India.

Son Valley

Introduction and Geographic Setting:

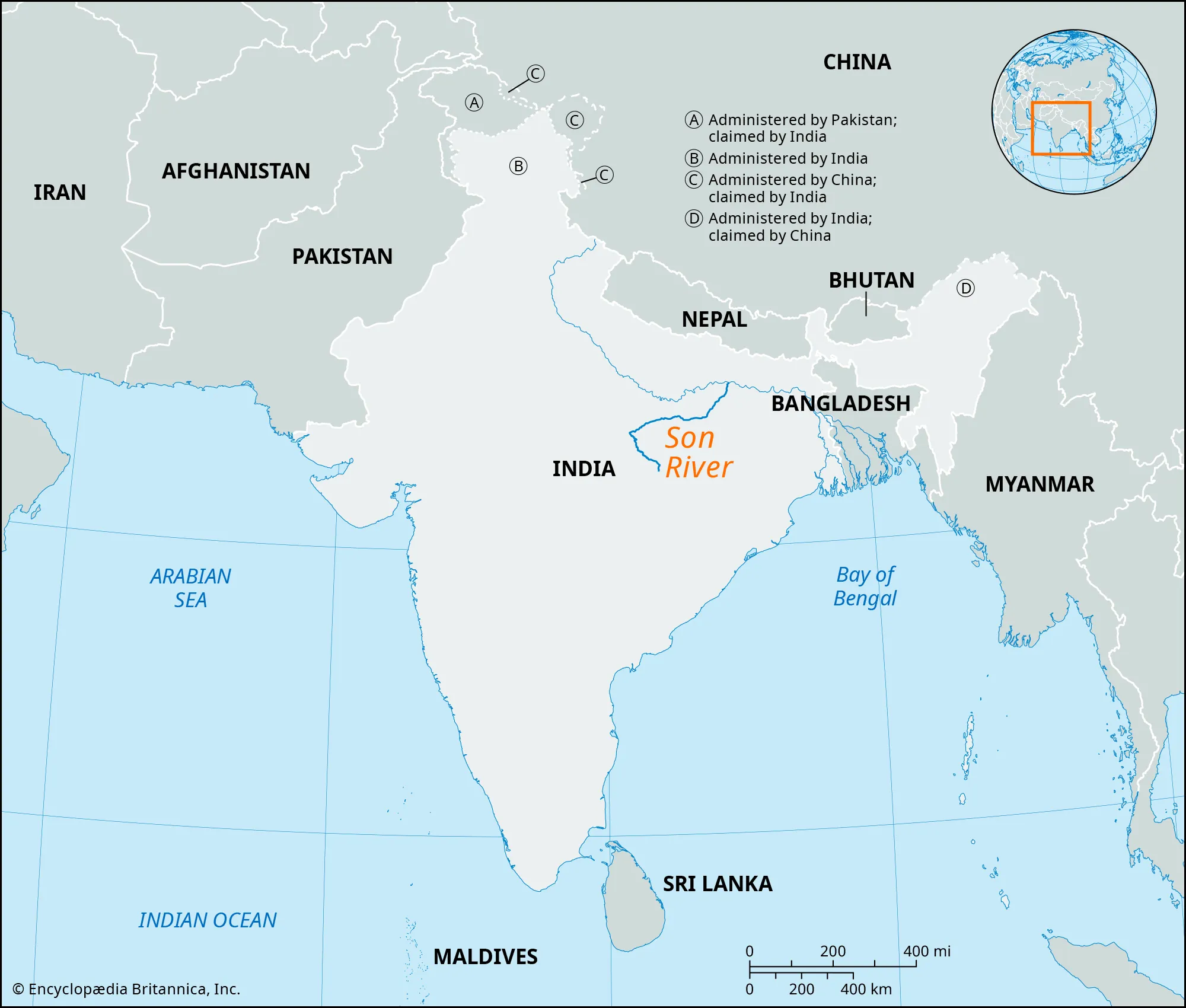

The Son Valley refers to the valley of the Son River (also spelled “Sone”), a major southern tributary of the Ganga River in north-central India. The river rises in the Amarkantak region of Chhattisgarh, flows through Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, then eastwards through Bihar to join the Ganga.

Geologically and archaeologically significant stretch of the Son Valley lies in the Vindhyan/Kaimur region where the river has incised a narrow, steep-walled vall ey bounded by sandstones to the north (Kaimur escarpment) and lower plains to the south.

Because of its valley morphology, extensive alluvial terraces and sedimentary deposits, the Son Valley preserves a long and continuous record of prehistoric occupation—from Lower Palaeolithic hand-axes through Middle and Upper Palaeolithic, and into microlithic and later phases.

Lower Palaeolithic Phase:

The Son Valley contains evidence of the Lower Palaeolithic industry, including large bifacial hand-axes and cleavers, often of the Acheulean type. A recent study in the upper Son valley recorded 1,348 lithic artefacts from Acheulean dated contexts, with abundant hand-axes and cleavers.

Stratigraphic work in the Middle Son valley shows that artefacts may date back into the Middle Pleistocene – for example instruments within alluvial sediments of the Sihawal Formation have been correlated with ages up to ~100,000 years for certain lithic assemblages.

This early phase indicates that hominins (likely archaic Homo spp.) inhabited the valley when the Son River was depositing thick alluvial gravels, thus giving the valley one of the longer Lower Palaeolithic sequences in central India.

Middle Palaeolithic Phase:

Following the Lower Palaeolithic, the valley reflects transitions to the Middle Palaeolithic. At the well-known site Dhaba (on the Son River bank) excavations revealed artefacts in sediment layers dated to ~80,000 to ~65,000 years ago using radiocarbon and geochronological methods. Tools employing the Levallois technique (a hallmark of Middle Palaeolithic technology) were recovered.

The discovery at Dhaba suggests continuity of human occupation through the period of the catastrophic Toba super‐eruption (ca. 74,000 years ago), as ash deposits corresponding to the eruption were found within the stratigraphy of the valley.

Thus the Middle Palaeolithic in the Son Valley exhibits technological change (smaller flakes, prepared cores, Levallois methods) and likely changes in behaviour and adaptation to climatic and environmental fluctuations in the Late Pleistocene.

Upper Palaeolithic / Microlithic Phase:

The transition to Upper Palaeolithic and microlithic tool-kits is documented in the valley: blade-based technologies, small flake/blade tools, backed points, lunates, etc. Evidence from sites in the Son Valley shows Late Palaeolithic tool-kits consistent with other Indian microlithic industries.

These phases correspond to the later Pleistocene and early Holocene when climatic amelioration occurred and humans diversified their subsistence strategies.

Later Prehistoric / Early Agricultural Phases:

While the Son Valley is richest for its Palaeolithic and microlithic record, there is also evidence of multi-cultural sites extending into later prehistory (Neolithic, chalcolithic) though less well documented compared to some adjacent valleys. Explorations in the Lower Son Valley (Uttar Pradesh) recovered sites with microlithic and multi-cultural contexts, expanding the geographical extent of later prehistoric occupation.

Environmental and Geological Context:

The stone tool deposits in the Son Valley are embedded in Quaternary alluvial sediments, including gravels, sands and silts deposited by the river system during alternating climatic regimes. The geomorphology has been studied: the late Quaternary alluvial history of the Middle Son valley has been compared to large river systems globally (e.g., Nile, Amazon) in terms of terrace formation and sedimentary sequences.

At multiple sites in the valley ash from the Toba eruption (ca. 74 ka) is preserved—this offers a useful chronological marker and suggests the region was occupied during major climatic events.

The valley’s raw-material base (quartzite, sandstone gravels) and its long alluvial terraces provided favourable conditions for early human occupation: tool manufacture, habitation, and exploitation of riverine and terrestrial resources. The dynamic river environment (with changing courses, terraces, floods) would have influenced human settlement, mobility and technological choices.

Key Archaeological Sites and Findings:

- Dhaba: On the Son River bank, this site has stratified evidence of Late Acheulean, Middle Palaeolithic and microlithic assemblages, with dating to ~80,000–65,000 years BP.

- Other Upper Son valley Acheulean sites (e.g., Mahuda, Chilhari, Semarpakha) recorded large numbers of hand-axes and cleavers.

- Numerous surface and terrace sites in the Middle and Lower Son valley have been documented: for example 48 Palaeolithic, microlithic and fossil sites in exploratory seasons of the Lower Son Valley (Uttar Pradesh) alone.

- The valley is one of the few Indian regions where the sequence from Lower through Middle to Upper Palaeolithic is reasonably well attested (though still incomplete).

Cultural and Archaeological Significance:

The Son Valley occupies a critical place in understanding early human occupation in the Indian subcontinent for several reasons:

- Long chronological span: The valley records human activity from possibly the Lower Palaeolithic (Acheulean) through Middle and Upper Palaeolithic into microlithic and later phases. This continuity is rare in Indian contexts.

- Technological transitions: The tool-kits show evolution—from large bifaces (hand-axes/cleavers) to prepared-core techniques (Levallois) to microlith/blade-based tools. This helps trace changes in hominin behaviour, adaptation, mobility and resource use.

- Environmental markers: Presence of Toba ash, detailed alluvial stratigraphy and terrace sequences mean the valley offers a cross-disciplinary record (geology, palaeoenvironment, archaeology) for studying human–environment interaction in the Late Pleistocene.

- Regional significance: The valley links upland zones (Vindhyan/Kaimur) and the Ganga plains, making it relevant for tracking human dispersals, settlement shifts, and adaptation of hominins in central/north-central India.

- Undervalued region: Compared to better-known sites in western India or the Deccan, the Son Valley still has many unexplored or under-published contexts, offering potential for future discovery and deeper insight.

Challenges and Research Directions:

Despite its importance, the Son Valley record also poses challenges:

- Precise dating of many tool-assemblages is still lacking. While relative stratigraphy is good in some sites, absolute dating (C14, OSL) remains to be extended.

- Stratigraphic complexity: River terraces, reworking, multistage deposition and re-depositing of artefacts make interpretation difficult; artefacts may be displaced from original contexts.

- Less documentation for later phases: While the Palaeolithic record is rich, the Neolithic/early farming phases in this region are less well known; more excavation is needed to understand the full prehistoric sequence.

- Preservation and survey: Modern land-use changes, erosion, and lack of systematic survey in parts of the valley hinder comprehensive mapping of all prehistoric sites.

- Integration with broader Indian prehistory: The Son Valley data needs to be better integrated with other regional sequences (e.g., Belan Valley, Narmada Valley) to place it in national and subcontinental frameworks.

Ancient Indian History Membership Required

You must be a Ancient Indian History member to access this content.