ECB 605 C

Population Studies – II

Semester – VI

Population Census in India and The Salient features of 2011

What is the census?

Census is nothing but a process of collecting, compiling, analyzing, evaluating, publishing and disseminating statistical data regarding the population. It covers demographic, social and economic data and are provided as of a particular date.

When was the first census in India held?

Census operations started in India long back during the period of the Maurya dynasty. It was systematized during the years 1865 to 1872, though it has been conducted uninterruptedly from the year 1881 being a trustworthy resource of information.

Why is the census important?

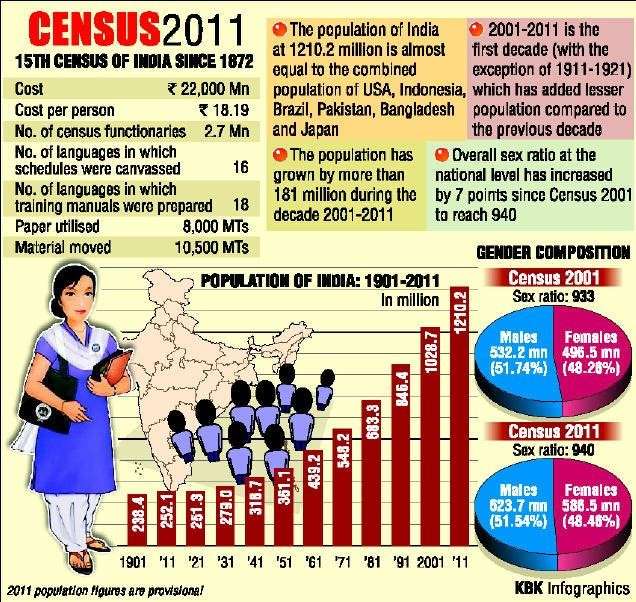

1. The Indian Census is the most credible source of information on Demography (Population characteristics), Economic Activity, Literacy and Education, Housing & Household Amenities, Urbanisation, Fertility and Mortality, Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, Language, Religion, Migration, Disability and many other socio-cultural and demographic data since 1872. Census 2011 is the 15th National Census of the Country. This is the only source of primary data in the village , town and ward level, It provides valuable information for planning and formulation policies for Central and the State Governments and is widely used by National and International Agencies, scholars, business people, industrialists, and many more.

2. The delimitation/reservation of Constituencies – Parliamentary/Assembly/Panchayats and other Local Bodies is also done on the basis of the demographic data thrown up by the Census. Census is the basis for reviewing the country’s progress in the past decade, monitoring the ongoing Schemes of the Government and most importantly, plan for the future.

Key findings of 2011 census

1. Population –

- India’s total population stands at 1.21 billion, which is 17.7 per cent more than the last decade, and growth of females was higher than that of males.

- There was an increase of 90.97 million males and increase of 90.99 million females. The growth rate of females was 18.3 per cent which is higher than males — 17.1 per cent. India’s population grew by 17.7 per cent during 2001-11, against 21.5 per cent in the previous decade.

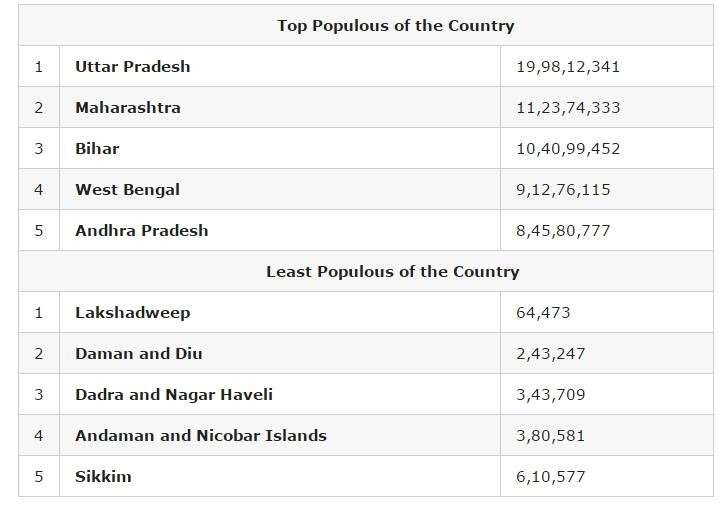

- Among the major states, highest decadal growth in population has been recorded in Bihar (25.4 per cent) while 14 states and Union Territories have recorded population growth above 20 per cent.

2. Rural and urban population –

- Altogether, 833.5 million persons live in rural area as per Census 2011, which was more than two-third of the total population, while 377.1 million persons live in urban areas. Urban proportion has gone up from 17.3 per cent in 1951 to 31.2 per cent in 2011. Empowered Action Group (EAG) states have lower urban proportion (21.1 per cent) in comparison to non-EAG states (39.7 per cent).

- Highest proportion of urban population is in NCT Delhi (97.5 per cent). Top five states in share of urban population are Goa (62.2 per cent), Mizoram (52.1 per cent), Tamil Nadu (48.4 per cent), Kerala (47.7 per cent) and Maharashtra (45.2 per cent).

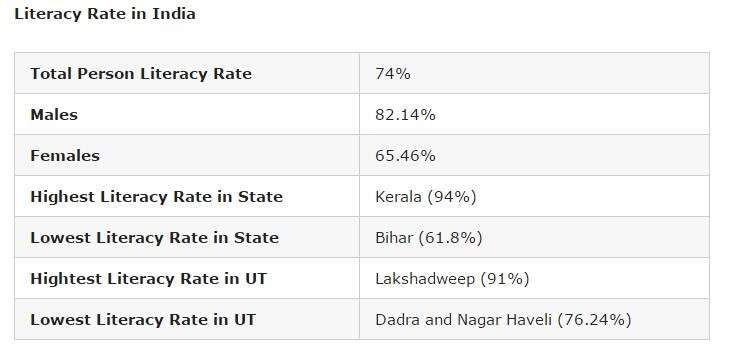

3. Literacy –

- Literacy rate in India in 2011 has increased by 8 per cent to 73 per cent in comparison to 64.8 per cent in 2001.

- While male literacy rate stands at 80.9 per cent – which is 5.6 per cent more than the previous census, the female literacy rate stands at 64.6 per cent — an increase of 10.9 per cent than 2001.

- The highest increase took place in Dadra and Nagar Haveli by 18.6 points (from 57.6 per cent to 76.2 per cent), Bihar by 14.8 points (from 47.0 per cent to 61.8 per cent), Tripura by 14.0 points (from 73.2 per cent to 87.2 per cent)

- Improvement in female literacy is higher than males in all states and UTs, except Mizoram (where it is same in both males and females) during 2001-11.

- The gap between literacy rate in urban and rural areas is steadily declining in every census. Gender gap in literacy rate is steadily declining in every census. In Census 2011, the gap stands at 16.3 points.

- Top five states and UTs, where literacy rate is the highest, are Kerala (94 per cent), Lakshadweep (91.8 per cent), Mizoram (91.3 per cent), Goa (88.7 per cent) and Tripura (87.2).

- The bottom five states and UTs are Bihar (61.8 per cent), Arunachal Pradesh (65.4 per cent), Rajasthan (66.1 per cent), Jharkhand (66.4 per cent) and Andhra Pradesh (67 per cent).

4. Density –

- The density of population in the country has also increased from 325 in 2001 to 382 in 2011 in per sq km. Among the major states, Bihar occupies the first position with a density of 1106, surpassing West Bengal which occupied the first position during 2001.

- Delhi (11,320) turns out to be the most densely inhabited followed by Chandigarh (9,258), among all states and UT’s, both in 2001 and 2011 Census. The minimum population density works out in Arunachal Pradesh (17) for both 2001 and 2011 Census.

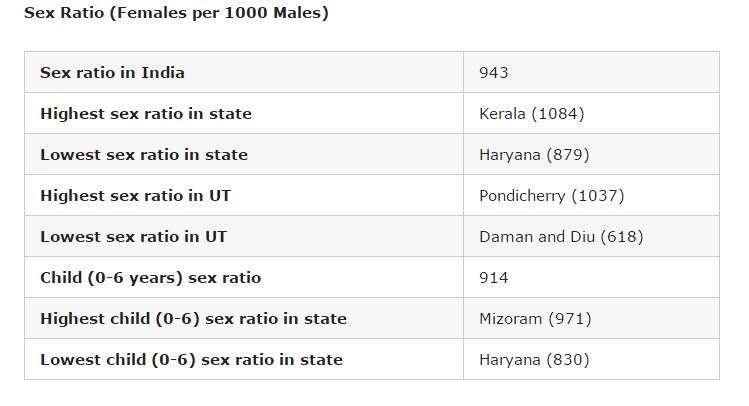

5. Sex ratio –

- The sex ratio of population in the country in 2011 stands at 940 female against 1000 males, which is 10 per cent more than the last census when the number female per thousand male stood at 933. Haryana has the dubious distinction of having the worst male-female ratio among all states while Kerala fares the best.

- The number of females per 1000 males in Haryana in 2011 stands at 879 followed by Jammu and Kashmir (889 female) and Punjab (895 females).

- The other two worst-performing states in terms of skewed sex ration are Uttar Pradesh (912 females) and Bihar (918 females).

- Five top performing states in terms of sex ratio were Kerala (1,084 females), Tamil Nadu (996), Andhra Pradesh (993), Chhattisgarh (991), Odisha (979).

6. Child population –

- Child population in the age of 0 to 6 years has seen an increase of 0.4 per cent to 164.5 million in 2011 from 163.8 million in 2001.

- The child population (0-6) is almost stationary. In 17 states and UTs, the child population has declined in 2011 compared to 2001.

- With the declaration of sex ratio in the age group 0-6, the Census authorities tried to bring out the recent changes in the society in its attitude and outlook towards the girl child. It was also an indicator of the likely future trends of sex ratio in the population.

- There has been a decline of 8 per cent in the sex ratio of 0-6 age group. In 2011, the child sex ratio (0-6) stands at 919 female against 1000 male in comparison to 927 females in 2001.

- Male child (0-6) population has increased whereas female child population has decreased during 2001-11. Eight states, Jammu and Kashmir, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, and Meghalaya have proportion of child population more than 15 per cent.

- The worst performing states in regard to sex ration in the age group of 0 to 6 years are Haryana (834 females), Punjab (846), Jammu and Kashmir (862), Rajasthan (888) and Gujarat (890).

- The best performing states are Chhattisgarh (969), Kerala (964), Assam (962), West Bengal (956) Jharkhand (948) and Karnataka (948).

7. SC/ST data –

- According to the Census, Scheduled Castes are notified in 31 states and UTs and Scheduled Tribes in 30 states. There are altogether 1,241 individual ethnic groups, etc. notified as SC’s in different states and UT’s.

- The number of individual ethnic groups, etc. notified as ST’s is 705. There has been some changes in the list of SC’s/ST’s in states and UT’s during the last decade.

- The SC population in India now stands at 201.4 million, which is 20 per cent more than the last census. The ST population stands at 104.3 million in 2011 – 23.7 per cent more than 2001.

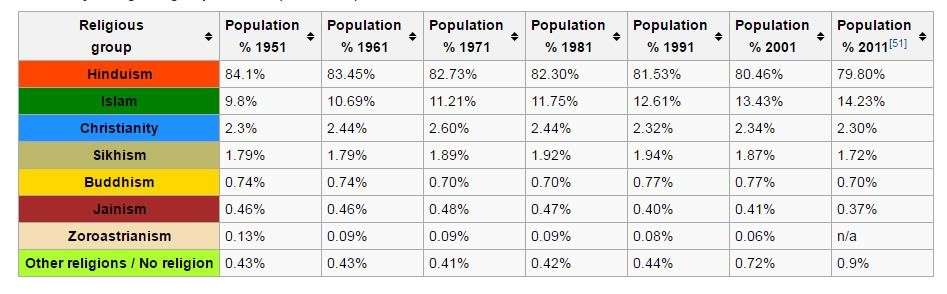

8. Religious demographics – The religious data on India Census 2011 was released by the Government of India on 25 August 2015. Hindus are 79.8% (966.3 million), while Muslims are 14.23% (172.2 million) in India. For the first time, a “No religion” category was added in the 2011 census. 2.87 million Were classified as people belonging to “No Religion” in India in the 2011 census. – 0.24% of India’s population of 1.21 billion. Given below is the decade-by-decade religious composition of India till the 2011 census. There are six religions in India that have been awarded “National Minority” status – Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Jains, Buddhists and Parsis.

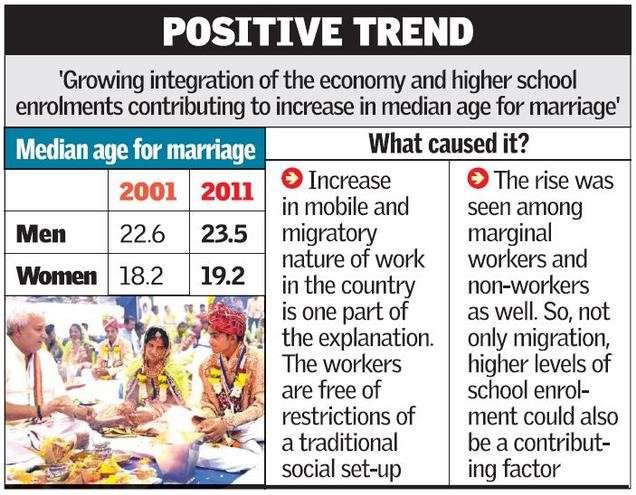

9. Median marriage age – The median age increased for men – from 22.6 (2001) to 23.5 (2011) and for women – from 18.2 (2001) to 19.2 (2011)

The salient features of census 2011

The most important feature of the data contained in Census 2011 and 2001 is that in terms of demographics the Hindus of India are a civilization in retreat. On the other hand Islam is in a fast forward mode. A projection of the future demographics of Hindus and Muslims upto 2050 by Pew Research Center of USA says that upto 2050 worldwide the Hindus will grow at the rate of 34 percent per decade, while Muslims will grow at the rate of 73 percent per decade. A demographically growing community tries to snatch more land, more jobs, more resources and finally demands a major say in the affairs of the besieged country. According to Samuel Huntington it leads to major faultline conflicts between the demographically retreating community and the demographically growing community. In terms of Huntington’s analysis a major civilizational clash between the retreating and advancing communities is inevitable.

The new challenge for Census 2021

Amid the anger and acrimony over the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), the National Population Register (NPR), and a possible National Register of Citizens (NRC), which the government has said has not been finalised yet, there has been little thought regarding its effects on another growing challenge — the quality of official data. In the last few years, official data has suffered from credibility issues and undermined confidence in the economy. The Indian statistical system, once the envy of the developing world, has fallen on hard times.

In 2020 and 2021, the government will roll out the 16th Census (and the 8th after Independence). The Census will be conducted in two phases — a house listing and housing Census to be conducted between April and September this year, followed by the population enumeration in February 2021.

The Census is the key source of primary data at the village, town and ward level, providing micro-level data on demography, housing, assets, education, economic activity, social groups, language and migration, among other variables. It also provides population data to the Delimitation Commission for the constitutionally-mandated decennial delimitation of parliamentary and assembly constituencies, and serves as a key input for many government policies and public services.

It is a massive exercise — and massively expensive. The cost of the 2021 Census is estimated at ~8,754 crore (and NPR at ~3,941 crore), involving about 30 lakh enumerators and field functionaries (generally government teachers and those appointed by state governments). Concurrently, the NPR — first prepared in 2010 under the provisions of the Citizenship Act, 1955 and Citizenship Rules, 2003 and subsequently updated in 2015 — will also be updated along with house listing and housing Census (except in Assam).

News reports have been streaming in that data collection exercises like the National Sample Survey (NSS) are being hampered in states like Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal. Reports from Karnataka indicate that people are declining to share personal information with officials visiting households in connection with government welfare schemes, with residents turning away ASHA workers on a pulse-polio visit, fearing that somehow some of their information might find its way into the NRC.

At its core, the fears of a tainted Census stem from the NPR breaking one of the cardinal rules in objective data collection, the preservation of anonymity. Anonymity must be maintained if people are to report information truthfully, especially information that can be used against them. Otherwise, people will report the information that is most likely to yield a beneficial outcome, whether minimising risk or maximising benefits, not what is true.

If respondents ascertain that truthfully revealing certain kinds of information in the NPR is more likely to result in questioning their citizenship, they may choose to obfuscate or misreport. Because the NPR and Census are to be run concurrently — and both are under the auspices of the Registrar General of the ministry of home affairs (also the key architect and driver of the CAA) — this loss of credible information is likely to extend to the Census. Thus, if the CAA and NPR are perceived as targeting a particular community, measuring that community, however genuine the intentions, through the Census, will simply not work.

Given that those born after July 1987 will have to offer proof of their parents’ citizenship, and some segments of citizens, especially Muslims, are particularly vulnerable to having their citizenship questioned, there will be considerable incentives for people to misreport age, religion and language data. But once the trust is broken between the person collecting the data and the person providing the data, then misreporting could spread to other parts of the Census as well. Worse yet, there is no objective way to detect this misreporting, leaving only ad hoc methods of rooting out misreporting that are bound to cause more harm than good.

The loss of credible Census data is an example of an economic principle known as Goodhart’s Law, which states that ‘‘as soon as a particular instrument or asset is publicly defined as money in order to impose monetary control, it will cease to be used as money and replaced by substitutes which will enable evasion of that control’’. In other words, when the measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. More broadly, measures that are targets simultaneously describe and prescribe, conflating the “what” with the “ought”.

The Census data is, by definition, a means to serve government goals. Assurances of data protection and integrity are unlikely to allay fears that the data gathered will not be used for citizenship purposes. Entire censuses have been stopped in countries such as Lebanon, Nigeria, and Pakistan because of fears that the results would favour certain groups, and led to the pulling out of the citizenship question in the 2020 US Census.

Sadly, the negative repercussions go beyond the Census. For example, good quality personal information is critical for many public health programmes. Incomplete data can have serious adverse effects on monitoring and evaluation, and, thereby programme outcomes. Indeed, surveys, in general, will be negatively affected since once distrust takes root, it becomes a generalised condition.

The compact between a State and its citizens is built on a foundation of trust, one that is based on a minimal presumption that people are citizens of that State to begin with. The erosion of that trust will undermine the Indian State’s ability to gather credible data. And a State that cannot collect objective data on its population will also find itself incapable of framing effective policies for its people.

National Family Health Survey 3, 4 & 5

- National Family Health Survey (NFHS):

- The NFHS is a large-scale, multi-round survey conducted in a representative sample of households throughout India.

- Conducted By:

- The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) has designated the International Institute for Population Sciences(IIPS) Mumbai, as the nodal agency for providing coordination and technical guidance for the survey.

- IIPS collaborates with a number of Field Organizations (FO) for survey implementation.

- Goals:

- Each successive round of the NFHS has had two specific goals:

- To provide essential data on health and family welfare needed by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and other agencies for policy and programme purposes.

- To provide information on important emerging health and family welfare issues.

- Each successive round of the NFHS has had two specific goals:

- The survey provides state and national information for India on:

- Fertility

- Infant and child mortality

- The practice of family planning

- Maternal and child health

- Reproductive health

- Nutrition

- Anaemia

- Utilization and quality of health and family planning services.

- Funding:

- The funding for different rounds of NFHS has been provided by USAID, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, UNICEF, UNFPA, and MoHFW (Government of India).

History of NFHS

- Objective: The main objective of each successive round of the NFHS has been to provide high-quality data on health and family welfare and emerging issues in this area.

- NFHS-1: The NFHS-1 was conducted in 1992-93.

- NFHS-2: The NFHS-2 was conducted in 1998-99 in all 26 states of India.

- The project was funded by the USAID, with additional support from UNICEF.

- NFHS-3: The NFHS-3 was carried out in 2005-2006.

- NFHS-3 funding was provided by the USAID, the Department for International Development (UK), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, UNICEF, UNFPA, and the Government of India.

- NFHS-4: The NFHS-4 in 2014-2015.

- In addition to the 29 states, NFHS-4 included all six union territories for the first time and provided estimates of most indicators at the district level for all 640 districts in the country as per the 2011 census.

- The survey covered a range of health-related issues, including fertility, infant and child mortality, maternal and child health, perinatal mortality, adolescent reproductive health, high-risk sexual behaviour, safe injections, tuberculosis, and malaria, non-communicable diseases, domestic violence, HIV knowledge, and attitudes toward people living with HIV.

National Family Health Survey-5

- The NFHS-5 has captured the data during 2019-20 and has been conducted in around 6.1 lakh households.

- Many indicators of NFHS-5 are similar to those of NFHS-4, carried out in 2015-16 to make possible comparisons over time.

- Phase 2 of the survey (covering remaining states) was delayed due to the Covid-19 pandemic and its results were released in September 2021.

- NFHS-5 data will be useful in setting benchmarks and examining the progress the health sector has made over time.

- Besides providing evidence for the effectiveness of ongoing programmes, the data from NFHS-5 help in identifying the need for new programmes with an area specific focus and identifying groups that are most in need of essential services.

- It provides an indicator for tracking 30 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that the country aims to achieve by 2030.

- NFHS-5 includes some new topics, such as preschool education, disability, access to a toilet facility, death registration, bathing practices during menstruation, and methods and reasons for abortion.

- NFHS-5 includes new focal areas that will give requisite input for strengthening existing programmes and evolving new strategies for policy intervention. The areas are:

- Expanded domains of child immunization

- Components of micro-nutrients to children

- Menstrual hygiene

- Frequency of alcohol and tobacco use

- Additional components of non-communicable diseases (NCDs)

- Expanded age ranges for measuring hypertension and diabetes among all aged 15 years and above.

- In 2019, for the first time, the NFHS-5 sought details on the percentage of women and men who have ever used the Internet.

- NFHS-5 includes new focal areas that will give requisite input for strengthening existing programmes and evolving new strategies for policy intervention. The areas are:

Key Findings of NFHS-5

- Sex Ratio: NFHS-5 data shows that there were 1,020 women for 1000 men in the country in 2019-2021.

- This is the highest sex ratio for any NFHS survey as well as since the first modern synchronous census conducted in 1881.

- In the 2005-06 NFHS, the sex ratio was 1,000 or women and men were equal in number.

- Sex Ratio at Birth: For the first time in India, between 2019-21, there were 1,020 adult women per 1,000 men.

- However, the data shall not undermine the fact that India still has a sex ratio at birth (SRB) more skewed towards boys than the natural SRB (which is 952 girls per 1000 boys).

- Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Punjab, Rajasthan, Bihar, Delhi, Jharkhand, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Odisha, Maharashtra are the major states with low SRB.

- Total Fertility Rate (TFR): The TFR has also come down below the threshold at which the population is expected to replace itself from one generation to next.

- TFR was 2 in 2019-2021, just below the replacement fertility rate of 2.1.

- In rural areas, the TFR is still 2.1.

- In urban areas, TFR had gone below the replacement fertility rate in the 2015-16 NFHS itself.

- A decline in TFR, which implies that a lower number of children are being born, also entails that India’s population would become older.

- The survey shows that the share of under-15 population in the country has therefore further declined from 28.6% in 2015-16 to 26.5% in 2019-21.

- TFR was 2 in 2019-2021, just below the replacement fertility rate of 2.1.

- Children’s Nutrition: Child Nutrition indicators show a slight improvement at all-India level as Stunting has declined from 38% to 36%, wasting from 21% to 19% and underweight from 36% to 32% at all India level.

- In all phase-II States/UTs the situation has improved in respect of child nutrition but the change is not significant as drastic changes in respect of these indicators are unlikely in a short span period.

- The share of overweight children has increased from 2.1% to 3.4%.

- In all phase-II States/UTs the situation has improved in respect of child nutrition but the change is not significant as drastic changes in respect of these indicators are unlikely in a short span period.

- Anaemia: The incidence of anaemia in under-5 children (from 58.6 to 67%), women (53.1 to 57%) and men (22.7 to 25%) has worsened in all States of India (20%-40% incidence is considered moderate).

- Barring Kerala (at 39.4%), all States are in the “severe” category.

- Immunization: Full immunization drive among children aged 12-23 months has recorded substantial improvement from 62% to 76% at all-India level.

- 11 out of 14 States/UTs have more than three-fourth of children aged 12-23 months with fully immunization and it is highest (90%) for Odisha.

- Institutional Births: Institutional births have increased substantially from 79% to 89% at all-India Level.

- Institutional delivery is 100% in Puducherry and Tamil Nadu and more than 90% in 7 States/UTs out of 12 Phase II States/UTs.

- Along with an increase in institutional births, there has also been a substantial increase in C-section deliveries in many States/UTs especially inprivate health facilities.

- It calls into question unethical practices of private health providers who prioritise monetary gain over women’s health and control over their bodies.

- Family Planning: Overall Contraceptive Prevalence Rate (CPR) has increased substantially from 54% to 67% at all-India level and in almost all Phase-II States/UTswith an exception of Punjab.

- Use of modern methods of contraceptives has also increased in almost all States/UTs.

- Unmet needs of family Planning have witnessed a significant decline from13% to 9% at all-India level and in most of the Phase-II States/UTs.

- The unmet need for spacing which remained a major issue in India in the past has come down to less than 10% in all the States except Jharkhand (12%), Arunachal Pradesh (13%) and Uttar Pradesh(13%).

- Breastfeeding to Children’s: Exclusive breastfeeding to children under age 6 months has shown an improvement in all-India level from 55% in 2015-16 to 64% in 2019-21. All the phase-II States/UTs are also showing considerable progress.

- Women Empowerment: Women’s empowerment indicators portray considerable improvement at all India level and across all the phase-II States/UTs.

- Significant progress has been recorded between NFHS-4 and NFHS-5 in regard to women operating bank accounts from 53% to 79% at all-India level.

- More than 70% of women in every state and UTs in the second phase have operational bank accounts.

Key Terms

- Total Fertility Rate (TFR) indicates the average number of children expected to be born to a woman during her reproductive span of 15-49 years.

- The replacement level is the number of children needed to replace the parents, after accounting for fatalities, skewed sex ratio, infant mortality, etc. Population starts falling below this level.

- Contraceptive Prevalence Rate (CPR) is the proportion of women who are currently using, or whose sexual partner is currently using, at least one method of contraception, regardless of the method being used.

- It is reported as a percentage with reference to women of respective marital status and age group.

- Sex ratio at birth (SRB) is defined as the number of female births per 1,000 male births. The SRB is a key indicator of a son’s preference vis-à-vis daughters.

- Stunting is the impaired growth and development that children experience from poor nutrition, repeated infection, and inadequate psychosocial stimulation.

- It is the result of chronic or recurrent undernutrition, usually associated with poverty, poor maternal health and nutrition, frequent illness and/or inappropriate feeding and care in early life.

- Wasting is defined as low weight-for-height. It often indicates recent and severe weight loss, although it can also persist for a long time. Wasting in children is associated with a higher risk of death if not treated properly.

- Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) is defined as the ‘number of deaths of children under the age of 1 year per 1000 live births for a given year.

- The country’s average IMR stands at 32 per 1,000 live births which includes an average 36 deaths for rural and 23 for urban areas.

Characteristics of Indian population

By demographic features we mean the characteristics of population like, size, composition, diversity, growth and quality of population etc.

To have basic understanding of the population problem of a specific country, one should have a complete knowledge regarding the basic features of population of that country.

The following are features of India’s population:

1. Large Size and Fast Growth:

The first main feature of Indian population is its large size and rapid growth. According to 2001 census, the population of India is 102.87 crore. In terms of size, it is the second largest population in the world, next only to China whose population was 127 crore in 2001. India’s population was 23.6 crore in 1901 and it increased to 102.7 crore in 2001.

In addition to its size, the rate of growth of population has been alarming since 1951. At present, India’s population is growing at a rate of 1.9 percent per annum; 21 million people are added every year which is more than the population of Australia. This situation is called population explosion and this is the result of high birth rate and declining death rate.

2. Second Stage of Demographic Transition:

According to the theory of demographic transition, the population growth of a country passes through three different stages as development proceeds. The first stage is characterised by high birth rate and high death rate. So in this stage the net growth of population is zero. Till 1921, India was in the 1st stage of demographic transition.

The second stage is featured by high birth rate and declining death rate leading to the rapid growth of population. India entered the second stage of demographic transition after 1921. In 1921-30 India entered the 2nd stage, the birth rate was 464 per thousand and death rate was 363 per thousand.

In 2000-01, birth rate was 25.8 and death rate declined to 85. This led to rapid growth of population. India is now passing through the second stage of demographic transition. While developed countries are in 3rd stage.

3. Rapidly Rising Density:

Another feature of India’s population is its rapidly rising density. Density of population means to the average number of people living per square kilometer. The density of population in India was 117 per square km. in 1951 which increased to 324 in 2001. This makes India one of the most densely populated countries of the world. This adversely affects the land-man ratio.

India occupies 2.4 per-cent of the total land area of the world but supports 16.7 per-cent of the total world population. Moreover, there is no causal relationship between density of population and economic development of a country. For example, Japan & England having higher density can be rich and Afghanistan & Myanmar having lower density can be poor. However in an underdeveloped country like India with its low capital and technology, the rapidly rising density is too heavy a burden for the country to bear.

4. Sex Ratio Composition Unfavourable to Female:

Sex ratio refers to the number of females per thousand males. India’s position is quite different than other countries. For example the number of female per thousand males was 1170 in Russia, 1060 in U.K., 1050 in U.S.A. whereas it is 927 in India according to 1991 census.

The sex ratio in India as 972 per thousand in 1901 which declined to 953 in 1921 and to 950 in 1931. Again, in 1951, sex ratio further declined to 946. In 1981, sex ratio reduced to 934 against 930 per thousand in 1971. During 1991, sex ratio was recorded 927 per thousand.

The sex ratio is 933 per thousand in 2001. State wise Kerala has more females than males. There are 1040 females per thousand males. The lowest female ratio was recorded in Sikkim being 832. Among the union territories Andaman and Nicobar Islands has the lowest sex ratio i.e. 760. Therefore, we can conclude that sex ratio composition is totally unfavourable to female.

5. Bottom heavy Age Structure:

The age composition of Indian population is bottom heavy. It implies that ratio of persons in age group 0-14 is relatively high. According to 2001 census, children below 14 years were 35.6%. This figure is lower than the figures of previous year. High birth rate is mainly responsible for large number of dependent children per adult. In developed countries the population of 0-14 age group is between 20 to 25%. To reduce the percentage of this age group, it is essential to slow down the birth rate.

6. Predominance of Rural Population:

Another feature of Indian population is the dominance of rural population. In 1951, rural population was 82.7% and urban population was 17.3%. In 1991 rural population was 74.3% and urban population was 257. In 2001, the rural population was 72.2% and urban population was 27.8. The ratio of rural urban population of a country is an index of the level of industrialisation of that country. So process of urbanisation slow and India continues to be land of villages.

7. Low Quality Population:

The quality of population can be judged from life expectancy, the level of literacy and level of training of people. Keeping these parameters in mind, quality of population in India is low.

(a) Low Literacy Level:

Literacy Level in India is low. Literacy level in 1991 was 52.2% while male-female literacy ratio was 64.1 and 39.3 percent. In 2001, the literacy rate improved to 65.4 percent out of which made literacy was 75.8 and female literacy was 52.1 percent. There are 35 crore people in our country who are still illiterate.

(b) Low level of Education and Training:

The level of education and training is very low in India. So quality of population is poor. The number of persons enrolled for higher education as percentage of population in age group 20-25 was a percent in 1982. It is only one fourth of the developed countries. The number of doctors and engineers per million of population are 13 and 16 respectively. It is quite less as compared to advanced countries.

(c) Low Life Expectancy:

By life expectancy we mean the average number of years a person is expected to live. Life expectancy in India was 33 years. It was increased to 59 in 1991 and in 2001, life expectancy increased to 63.9. Decline in death rate, decline in infant mortality rate and general improvement in medical facilities etc. have improved the life expectancy. However life expectancy is lower in India as compared to life expectancy of the developed nations. Life expectancy is 80 year in Japan and 78 years in Norway.

8. Low Work Participation Rate:

Low proportion of labour force in total population is a striking feature of India’s population. In India, Labour force means that portion of population which belongs to the age group of 15-59. In other words, the ratio of working population to the total is referred to as work participation rate.

This rate is very low in India in comparison to the developed countries of the world. Total working population was 43% in 1961 which declined to 37.6% in 1991. This position improved slightly to 39.2% in 2001. That means total non-working population was 623 million (60.8 percent) and working population was 402 million (39.2%). Similarly low rate of female employment and bottom-heavy age structure are mainly responsible for low work participation in India.

9. Symptoms of Over-population:

The concept of over-population is essentially a quantitative concept. When the population size of the country exceeds the ideal size, we call it over-population. According to T.R. Malthus, the father of demography, when the population of a country exceeds the means of substance available, the country faces the problem of over-population.

No doubt, food production has increased substantially to 212 million tonnes but problems like poverty, hunger, malnutrition are still acute. Agriculture is overcrowded in rural areas of the country which is characterised by diminishing returns. This fact leads to the conclusion that India has symptoms of over-population. Indian low per capita income, low standard of living, wide spread unemployment and under-employment etc. indicate that our population size has crossed the optimum limit.

Birth, Death and Population Growth Rates in India

Introduction

India is the second most populated country in the world. In land area, India ranks seventh globally. The population of India contributes nearly 17.70% share of the world’s population. Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra and Bihar are India’s top three most populated states. In contrast, Sikkim is the least populated state in the country. At present, China is the most populous country globally, but the birth rate and growth rate of India’s population indicate that India might surpass China’s population in the coming years. Here are some interesting facts about various aspects of India’s demography.

The Birth Rate in India

- As per United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), 67,385 babies are born per day in India. This is one-sixth of the total childbirth in the world.

- The annual birth rate in India accounts for one-fifth of the world’s yearly childbirth. Approximately 25 million babies are born per year in India.

- The crude birth rate in India is 17 births per 1000 persons. The natural birth rate is the live births per thousand population in a year, estimated at mid-year.

- By the United Nations (UN) World population prospect, the sex ratio at birth in India is 110 boys for every 100 girls.

- In India, Bihar has the highest birth rate, followed by Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan.

- The lowest birth rate in India is reported in Kerala, followed by Punjab, Tamil Nadu and West Bengal.

The Death Rate in India

- The mortality rate or death rate is defined as the number of deaths in a particular population during a specific time.

- According to World Bank’s data, the mortality rate or crude death rate in India is 7.30 per 1000 persons.

- In India, approximately 26789 deaths are reported per day.

- In the 2019 survey, India’s Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) was 30 deaths per 1000 live births.

- In 2019, the female mortality rate was 145.05 per 1000 female adults, and the male mortality rate was 201.4 per 1000 male adults in India.

The Population Growth Rate of India

As per the United Nations (UN) estimates, the population of India in 2022 will be 140 crores, and the present growth rate of the population is 1%. In the past decades, the growth rate of India’s population has significantly declined, but it is still higher than the population growth rate of China. It is estimated that India will surpass China and become the most populated country by 2030. However, after it, the population growth rate will become stagnant and then start to decline. It is expected that the population of India will reach its peak level by 2060 with 1.65 billion people, and then it will begin to decrease.

India is one of the youngest nations in the world. More than 50% of India’s population is below the age of 25, and only 5% of the people of India are above the age of 65 years.

Male and Female Population Statistics of India

As per the fifth National Family and Health Survey (NFHS), the male and female ratio in India is 1020 women for every 1000 men. For the first time in the history of India, it has more women than men. As per the 2015-16 NFHS survey, the ratio was 991 females for every 1000 males.

However, the sex ratio at birth in 2020-21 is 937 female births for every 1000 male births. It still indicates that the problem of sex selection before the birth of the child and female foeticide is still not completely resolved.

The Fertility Rate in India

As per the fifth National Family and Health Survey (NFHS), the fertility rate in India as of 2021 is 2. The highest fertility rate in the country is recorded in Bihar, with three children per woman, followed by Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan.

The Negative Impact of Population Growth on the Country

- It leads to unemployment as there are more job seekers than the job opportunities evolving in the country.

- When the population growth rate is higher than the country’s economic growth rate, it reduces the per capita income, resulting in inflation and poverty.

- The rise in population results in a vicious circle of unemployment, poverty and illiteracy.

Conclusion

India occupies only 2.14% of the world’s land area, but in terms of the population, its share is 18% of the world’s population. India is among the youngest nations, with a majority population of fewer than 35 years of age. India can emerge as one of the strongest and most developed nations. It is vital to act on necessary measures to realise the true potential of the young Indians. India is a versatile country with more than two thousand ethnic groups. It is important to lower the growth rate of the population to maintain a balanced approach toward the sustainable development of the country.

Life Expectancy

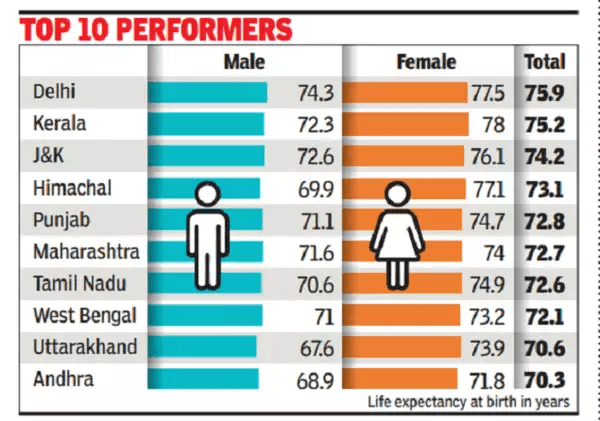

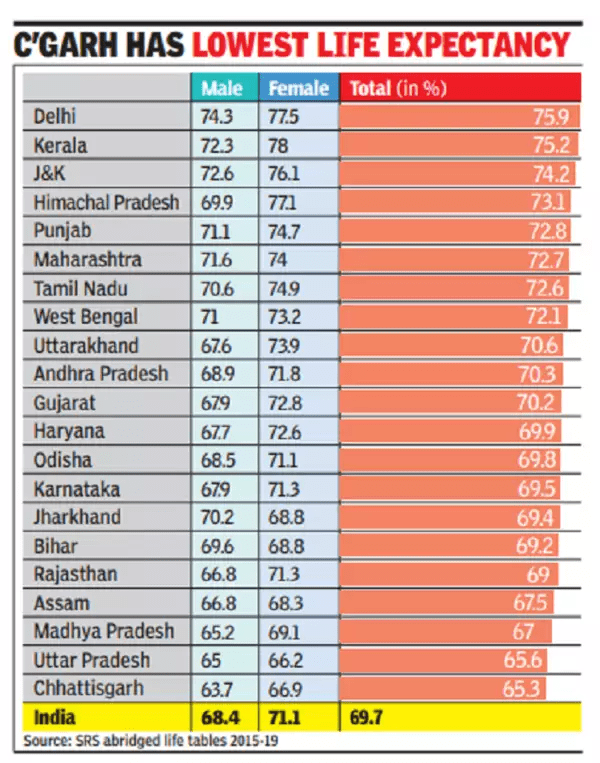

- India’s life expectancy at birth inched up to 69.7 in the 2015-19 period, well below the estimated global average life expectancy of 72.6 years.

- It has taken almost ten years to add two years to life expectancy.

Major Points

- Data shows that the gap between life expectancy at birth and life expectancy at age one or age five is the biggest in states with the highest infant mortality (IMR), Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh.

- In Uttar Pradesh, with the second highest IMR of 38, life expectancy jumps the highest, by 3.4 years, on completion of the first year.

- Over a 45-year period, India had added about 20 years to its life expectancy at birth from 49.7 in 1970-75 to 69.7 by 2015-19.

- Odisha has had the highest increase, of over 24 years, from 45.7 to 69.8 years followed by Tamil Nadu, where it increased from 49.6 to 72.6.

- Within India, there are huge variations across states and between urban and rural areas.

- Urban women in Himachal Pradesh had the highest life expectancy at birth of 82.3 years while at the other end, rural men in Chhattisgarh had the lowest, just 62.8 years, a gap of 15.8 years.

- Comparison with neighbouring countries

- In the neighbourhood, Bangladesh and Nepal, which had lower IMRs than India (24 compared to 28), now have higher life expectancy at birth of 72.1 and 70.5 respectively, according to the UN’s Human Development Report, 2019.

- Japan has the highest life expectancy of 85. Norway, Australia, Switzerland and Iceland had a life expectancy of 83. The Central African Republic had the lowest life expectancy of 54 followed by Lesotho and Chad at 55 in 2020.

Life Expectancy

- It is an estimate of the average number of additional years that a person of a given age can expect to live.

- The most common measure of life expectancy is life expectancy at birth.

- Life expectancy is a hypothetical measure.

- It assumes that the age-specific death rates for the year in question will apply throughout the lifetime of individuals born in that year.

- The estimate, in effect, projects the age-specific mortality (death) rates for a given period over the entire lifetime of the population born (or alive) during that time.

- The measure differs considerably by sex, age, race, and geographic location.

- Therefore, life expectancy is commonly given for specific categories, rather than for the population in general. For example, the life expectancy for white females in the United States who were born in 2003 is 80.4 years.

Infant and Maternal Mortality Rate in India

Infant Mortality Rate:

The Infant Mortality Rate or IMR is the number of deaths of children (under one year of age) per 1000 live births. On the other hand, the death rate of children under five year of age is called Child Mortality Rate.

Infant Mortality Rate

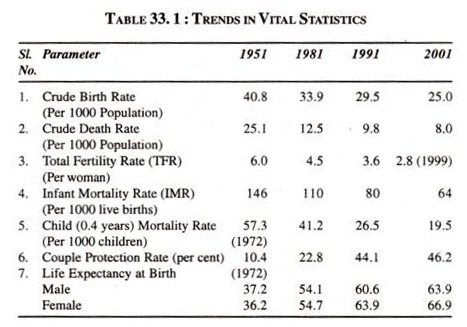

According to data presented by the Census of India – “The infant mortality rate, which plays an important role in health planning, has shown a considerable decline from 129 per 1000 live births in 1971 to 110 in 1981 and from 80 in 1991 to 33 in 2017.”

- This rate for a region is calculated by dividing the number of deaths of children less than 1 year old by the number of live births in a year times 1000.

- The major causes of congenital infant mortality are sudden infant death syndrome, malformations, accidents, maternal complications during the pregnancy and unintentional injuries.

- Contributing causes are social and environmental obstacles that prevent the availability of basic medical resources. 99% of the deaths of infants take place in developing nations. Among these, 86% are caused due to premature births, infections, delivery complications, birth injuries and perinatal asphyxia.

Infant Mortality Rate in India

- AS per Census 2011, The infant mortality rate, which plays an important role in health planning, has shown a considerable decline from 129 per 1000 live births in 1971 to 110 in 1981 and from 80 in 1991 to 44 in 2011. The child mortality rate has depicted a perceptible decline from 51.9 in 1971 to 41.2 in 1981 and from 26.5 in 1991 to 12.2 in 2011.

- Also, World Bank has indicated 28.3 as Infant Mortality Rate of India for 2019.

- According to the latest sample registration system Bulletin, Infant Mortality Rate in Kerala – 7 (updated)

- Infant Mortality Rate in Madhya Pradesh – 48 (updated)

- In India, Nagaland has the best Infant Mortality Rate which is at 4.

- As per RBI, the Infant Mortality Rate of the National Capital Delhi is 13.

- The infant mortality rate among females is higher than among males in all Indian states except:

- Chhattisgarh

- Delhi

- Madhya Pradesh

- Tamil Nadu

- Uttarakhand

Note: The 32 is the IMR at the national level. The rate varies between 6.9 and 5.0 in urban areas and rural areas respectively.

Replacement Rate

- In the case of no female mortality until the culmination of childbearing age (44/45/49), the replacement level of the TFR would be quite near 2.

- The current India Total Fertility Rate is 2.2 (2020).

- The lowest TFR 2019-2020 as per National Family Health Survey 5 is recorded in Sikkim (1.1). Bihar has the highest TFR – 3 (in 2005-06 the TFR was 4).

- According to the latest National Family Health Survey (NFHS), the TFR across most Indian states declined in the past half a decade, more so among urban women.

- The fertility rate of women in rural areas sharply dropped in Jammu and Kashmir, Maharashtra, Assam, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, and Bihar, while the fertility rate of women in urban areas went below-replacement fertility across all 21 states except Bihar, where it has remained unchanged at 2.4 since 2015-16.

Maternal Mortality Rate:

Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR) is defined as the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births due to pregnancy or termination of pregnancy, regardless of the site or duration of pregnancy. The maternal mortality rate is used to represent the risk associated with pregnancy among women.

In developing countries, the leading cause of death and disability among women of reproductive age are the complications that occur during childbirth and pregnancy.

Maternal Mortality Rate in India

In India, the number of deaths caused due to pregnancy and childbirth has been very high over the years but recent records show that there has been a decline in the MMR of India. It is tough to calculate the exact maternal mortality except where the comprehensive records of deaths and causes of death are available. So surveys and census are used to estimate the levels of maternal mortality.

Reproductive Age Mortality Studies (RAMOS) is presently considered the best way to calculate MMR. In this, different sources and records are analysed to get data regarding the death of women of reproductive ages and also through verbal autopsy to estimate the number of deaths. The MMR is calculated at both global and regional level every five years through a regression model.

In India, the Sample Registration Survey (SRS) is used to get an estimate of the maternal mortality rate. The Office of the Registrar General’s Sample Registration System (SRS) has released a special bulletin on Maternal Mortality in India in March 2022.

Major observations as per the Survey –

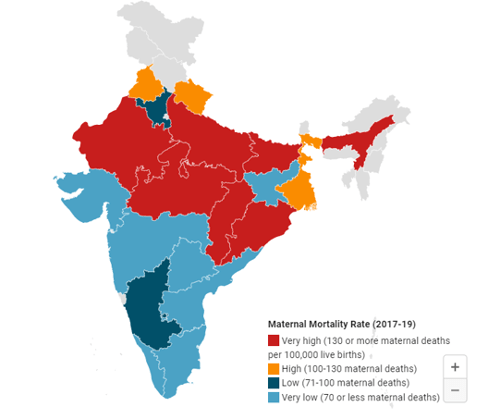

- As per the special bulletin there has been a decline of 10 points in the maternal mortality rate of India. India’s maternal mortality ratio (MMR) has improved to 103 in 2017-19, from 113 in 2016-18, marking an 8.8% decline.

- This is in sync with the trend of progressive reduction in the MMR over the years. With this persistent decline, India is on the verge of achieving the National Health Policy (NHP) target of 100/lakh live births by 2020 and certainly on track to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of 70/ lakh live births by 2030

- Currently seven states have achieved the Sustainable Development Goal (3.1) target. This marks an improvement compared to last survey when only five states had reached the target. Currently these states include Kerala (30), Maharashtra (38), Telangana (56), Tamil Nadu (58), Andhra Pradesh (58), Jharkhand (61), and Gujarat (70).

- Currently there are nine States that have achieved the MMR target set by the National Health Policy. This includes the above seven states along with Karnataka (83) and Haryana (96).

- Despite an improvement in the national average, some states continue to witness high levels of maternal mortality rates.

| Definition | States | |

| Very high maternal mortality | 130 or more maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. | Bihar (130), Odisha (136), Rajasthan (141), Chhattisgarh (160), Madhya Pradesh (163), Uttar Pradesh (167) and Assam (205). |

| High maternal mortality: | 100-130 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. | Uttarakhand (101), West Bengal (109) and Punjab (114). |

| Low maternal mortality: | 71-100 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. | Karnataka (83) and Haryana (96). |

- The states of Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Bihar have seen the most drop in MMR in absolute numbers. These states continue to have high level MMRs despite the improvement.

- Uttar Pradesh reported a decline of 30 points, Rajasthan (23 points) and Bihar (19 points).

- A remarkable fall of more than 15 percent has been observed in the states of Kerala, Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh.

- The top state with the lowest MMR is Kerala while the state with the highest MMR is Assam.

- Notably states like West Bengal, Haryana, Uttarakhand and Chhattisgarh have recorded an increase in MMR over the last survey in contrast to the national trend.

Given below is the MMR in India as per the Sample Registration System:

| Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR) in India | |

| Year | MMR |

| 2004-2006 | 254 |

| 2007-2009 | 212 |

| 2010-2012 | 178 |

| 2011-2013 | 167 |

| 2014-2016 | 130 |

| 2015-2017 | 122 |

| 2016-2018 | 113 |

| 2017-2019 | 103 |

The above data clearly shows the decline in the trend of maternal mortality rate in India. In the survey conducted in 2015-2017, Kerala was the state with the least maternal mortality rate of 42 and Assam noted the maximum number of deaths of women in India with MMR of 229.

Causes of High Maternal Mortality Rate

There are various reasons for the death of women during their reproductive age (18 to 39 years)that had been the cause of an increase in the maternal mortality rate. Given below are a few reasons for the rate of deaths of women due to pregnancy and childbirth:

- Spread of diseases

- Unawareness

- Lack of nutrition and unhealthy livelihood

- Haemorrhage

- Incorrect Treatment

Studies have shown that most deaths during pregnancy and childbirth are curable and can be controlled if proper treatment is provided to women. It has also been noted that calculating the exact MMR is not possible as multiple records of deaths are not recorded for reasons like abortion, ill-treatment and lack of medical attribution.

Result of MDG and SDG with respect to Maternal Mortality Rate

The Millennium Development Goals were set UNDP for all the member nations of the UN. MDG was a set of eight goals that were set for a better future of the world and the people living in it. The Sustainable development goals were undertaken by the members of the UN after a fifteen-year successful plan of the MDG.

The Millennium Development goals were successful in reducing poverty and infant mortality rate almost half since 1990. The latest report of Sustainable development goals released for 2019 has stated that a major decline in the number of deaths caused due to pregnancy and childbirth has been noted across the world.

The report also states that between 2015 and 2018, there has been an increase of 81 per cent assistance provided to pregnant ladies and that has been one of the major reasons for the decline in MMR. In 2018, the report released by SDG stated a decline of 37 per cent in the maternal mortality rate since 2000.

The sustainable development goals intend to attain their target of 70 deaths per 100,000 by 2030 with respect to the maternal mortality rate. Many actions have been taken for a better livelihood and proper assistance is being provided to reproductive women and awareness is being spread with an intention to end the maternal mortality rate across the world.

Maternal Mortality Rate in India – Reasons for Decline

The following programs implemented by the government is playing a crucial role in reducing the Maternal Mortality Rate in India.

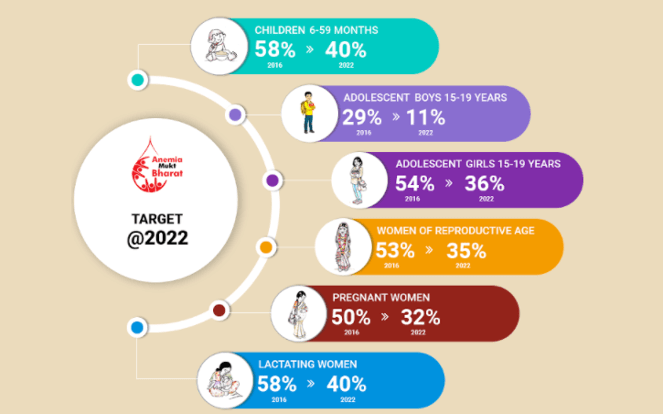

Anaemia Mukt Bharat (AMB)

- Anaemia Mukt Bharat (AMB) strategy was launched in 2018 with the objective of reducing anaemia prevalence among children, adolescents and women in the reproductive age group.

- It focusses on six target beneficiary groups, through six interventions and six institutional mechanisms to achieve the envisaged target under the POSHAN Abhiyan.

- The 6 interventions include supply of iron and folic acid supplements, deworming, behaviour change communication campaign, testing for anaemia, provision of iron and folic acid fortified foods in government-funded health programmes and addressing of non-nutritional causes of anaemia in endemic pockets with a special focus on malaria and fluorosis.

Surakshit Matratva Ashwasan (SUMAN):

- The Surakshit Matritva Aashwasan (SUMAN) has been launched by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare in 2019.

- It aims to provide assured, dignified and respectful delivery of quality healthcare services at no cost and zero tolerance for denial of services to any woman and newborn visiting a public health facility in order to end all preventable maternal and newborn deaths and morbidities and provide a positive birthing experience.

- Under the scheme, all pregnant women, newborns and mothers up to 6 months of delivery will be able to avail of several free health care services such as four antenatal check-ups and six home-based newborn care visits.

Anmol app:

- It is a multifaceted mobile tablet-based android application of the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare (MoHFW) for early identification and tracking of the individual beneficiary.

- The application would help to ensure tracking of beneficiaries for proper health care and promote family planning methods being adopted by them. The system also facilitates to ensure timely delivery of full competence of antenatal, postnatal & delivery services and tracking of children for complete immunization services.

LaQshya – Labour Room Quality Improvement Initiative

- This program focuses on Public Health facilities to help. They will be assisted by helping them improve their maternity operation theatres, and help augment the quality of care in labour rooms.

- This program will be implemented in all Community Health Centres (CHC), First Referral Unit (FRU), District Hospitals, Medical College Hospitals.

Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY)

- Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY) is implemented by the Ministry of Women and Child Development.

- PMMKVY came into effect from 1st January 2017.

- This Maternity Benefit Program is implemented in all districts.

- On fulfilling certain conditions, the beneficiaries would receive Rs 5,000 in 3 instalments.

- Cash benefits would be directly transferred to the bank accounts of the beneficiaries.

- Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana – Common Application Software (PMMVY – CAS) is used for monitoring this program.

Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY)

- This scheme is completely sponsored by the Government of India.

- Janani Suraksha Yojana comes under the National Health Mission.

Pradhan Mantri Surakshit Matritva Abhiyan (PMSMA)

- This program was launched with the objective of detecting and treating cases of anaemia.

Population and Economic Development of India

Population and development are correlated. It is stated that the size of population, rate of growth and population composition, and its geographical distribution are important factors in determining the requirements of infrastructure, such as education, housing, health services, food supply, etc. Productive health capacity is also determined by the size and growth rate of population.

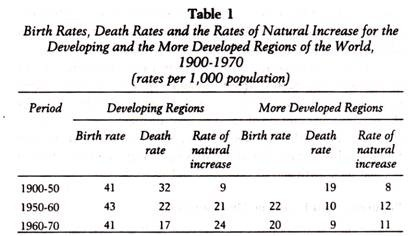

Thus, to make development plans for the present as well as for the future, there is a need to understand the structure and growth of population. A comparison of the developing countries and the more developed countries shows that the birth rate has been high in both categories, but the difference is still quite significant. Table 1 shows the facts in this context.

The developing countries are faced with several contradictions ‘n regard to population growth and economic and social development. For example, the birth rate has largely been static from 1900 to 1970, and the death rate has declined considerably because of the development in scientific and economic fields.

Thus, the increase in the population has been phenomenal – almost three times – from 1900 to 1970. The increase in the population of the developed countries has been just nominal. The birth rate has also declined to the extent of nearly 20 per cent. This clearly shows that along with scientific, technological and educational factors, population is a very important variable in economic development.

Since 1970 we notice a phenomenal change in birth and death rates and rate of natural increase in both developing and more developed countries. In 2002, in the developing countries, birth rate had declined to 24 from 41, and death rate to 8 from 17 per thousand.

Natural increase also declined from 24 to 16. The birth rate was also on decline in developing countries as from 20 it slide down to 11. Death rate was nearly stable as it was 9 in 1970 and 10 in 2002. However, natural increase declined to 1 from 10. Thus, the pressure of population is still a vital factor in the developing countries.

Several studies in developing countries have examined correlations between fertility levels in these countries and their social and economic development. These studies indicate that “improving economic and social conditions is not likely to have much impact in bringing down fertility in developing countries until a certain threshold level of development is achieved”. Since 1950s, the developing countries have shown their genuine concern for formulating suitable population policies.

Migration

Meaning of Migration:

Migration is the third factor for changes in the population, the other being birth rate and death rate. As compared to birth rate and death rate, migration affects the size of population differently. Migration is not a biological event like birth rate and death rate, but is influenced by the social, cultural, economic and political factors.

Migration is carried by the decision of a person or group of persons. The changes occurring in the birth rate and death rate do not affect the size and structure of the population on a large scale, while migration, at any time, may cause large scale changes in the size and structure of the population.

The study of migration is of vital importance because the birth rate, death rate and migration determine the size of population, the population growth rate and thus the structure of population. In addition, migration plays an important role in determining the distribution of population and supply of labour in the country.

Thus, the study of migration is also useful for formulating economic and other policies by the government, economists, sociologists, politicians, and planners along with demographers

Migration shows the trends of social changes. From the historical viewpoint during the process of industrialisation and economic development, people migrate from farms to industries, from villages to cities, from one city to another and from one country to another. In modern times, technological changes are taking place in Asia, Africa and Latin America due to which these regions are witnessing large-scale migration from rural to urban areas.

Economists are interested in the study of migration because migration affects the supply of skilled and semi-skilled labourers, development of industries and commerce causing changes in the employment structure of the migrated people. Formulation of economic policies has a close relation with the process of migration because migration affects the economic and social development of a country.

Out of the many side effects of the population growth in India and other developing countries, an important effect of industrialisation and economic development is the internal migration of the population on a large scale, which has drawn the attention of planners and formulaters of economic policies. Thus, migration is a demographic event, whose long term effects fall on the socioeconomic and cultural development of any region or country.

Migration is the movement of people between regions or countries. It is the process of changing one’s place of residence and permanently living in a region or country. According to the Demographic Dictionary of United Nations, “Migration is such an event in which people move from one geographical area to another geographical area. When people leaving their place of residence go to live permanently in another area then this is called migration.”

Migration may be permanent or temporary with the intention of returning to the place of origin in future.

Types of Migration:

Migration is of the following types:

(i) Immigration and Emigration:

When people from one country move permanently to another country, for example, if people from India move to America then for America, it is termed as Immigration, whereas for India it is termed as Emigration.

(ii) In-migration and Out-migration:

In-migration means migration occurring within an area only, while out-migration means migration out of the area. Both types of migration are called internal migration occurring within the country. Migration from Bihar to Bengal is in-migration for Bengal, while it is out- migration for Bihar.

(iii) Gross and Net Migration:

During any time period, the total number of persons coming in the country and the total number of people going out of the country for residing is called gross migration. The difference between the total number of persons coming to reside in a country and going out of the country for residing during any time period is termed as net migration.

(iv) Internal Migration and External Migration:

Internal migration means the movement of people in different states and regions within a country from one place to another. On the other hand, external or international migration refers to the movement of people from one country to another for permanent settlement.

Concepts Relating to Migration:

Besides, the following concepts are used in migration:

(i) Migration Stream:

Migration stream means the total number of people migrating from one region to another or from one country to another for residing during a time period. It is, in fact, related to the movement of people from a common area of origin to a common area of a destination. For example, migration of Indians to America during a time interval.

(ii) Migration Interval:

Migration may occur continuously over a period of time. But to measure it correctly, the data should be divided into intervals of one to five or more years. The division relating to a particular period is known as migration interval.

(iii) Place of Origin and Place of Destination:

The place which people leave is the place of origin and the person is called an out-migrant. On the other hand, the place of destination is the place where the person moves and the person is called an in-migrant.

(iv) Migrant:

Migrant is the labour which moves to some region or country for short periods of time, say several months or a few years. It is regarded as a secondary labour force.

Effects of Migration:

Internal migration affects the place where from people migrate and the place to which they migrate. When the migrants move from rural to urban areas, they have both positive and negative effects on the society and economy.

(i) Effects on Rural Areas:

Migration affects rural areas (the place of origin) in the following ways:

1. Economic Effects:

When population migrates from rural areas, it reduces the pressure of population on land, the per worker output and productivity on land increases and so does per capita income. Thus family income rises which encourages farmers to adopt better means of production thereby increasing farm produce.

Those who migrate to urban areas are mostly in the age group of 18-40 years. They live alone, work and earn and remit their savings to their homes at villages. Such remittances further increase rural incomes which are utilised to make improvements on farms which further raise their incomes. This particularly happens in the case of emigrants to foreign countries who remit large sums at home.

Moreover, when these migrants return to their villages occasionally, they try to raise the consumption and living standards by bringing new ideas and goods to their homes. Modern household gadgets and other products like TV, fridge, motor cycles, etc. have entered in the majority of rural areas of India where larger remittances flow from urban areas.

Further, with the migration of working age persons to urban areas the number of farm workers is reduced. This leads to employment of underemployed family members on the farm such as women, older persons and even juveniles.

Further, out-migration widens inequalities of income and wealth in rural area families which receive large remittances and their incomes rise. They make improvements on their farms which raise productivity and production. These further increase their incomes. Some even buy other farm lands. Thus such families become richer as compared to others, thereby widening inequalities.

2. Demographic Effects:

Migration reduces population growth in rural areas. Separation from wives for long periods and the use of contraceptives help control population growth. When very young males migrate to urban areas, they are so influenced by the urban life that they do not like to marry at an early age.

Their aim is to earn more, settle in any vocation or job and then marry. Living in urban areas makes the migrants health conscious. Consequently, they emphasise on the importance of health care, and cleanliness which reduces fertility and mortality rates.

3. Social Effects:

Migration also affects the social set-up of rural communities. It weakens the joint family system if the migrants settle permanently in urban areas. With intermingling of the migrants with people of different castes and regions in cities, they bring new values and attitudes which gradually change old values and customs of ruralites. Women play a greater role in the social setup of the rural life with men having migrated to towns.

(ii) Effects on Urban Areas:

Migration affects urban areas (or the place of destination) in the following ways:

1. Demographic Effects:

Migration increases the population of the working class in urban areas. But the majority of migrants are young men between the ages of 15 to 24 years who are unwed. Others above this age group come alone leaving their families at home.

This tendency keeps fertility at a lower level than in rural areas. Even those who settle permanently with their spouses favour small number of children due to high costs of rearing them. The other factor responsible for low fertility rate is the availability of better medical and family planning facilities in urban areas.

2. Economic Effects:

The effects of migration on income and employment in urban areas are varied depending upon the type of migrants. Usually the migrants are unskilled and find jobs of street hawkers, shoeshine boys, carpenters, masons, tailors, rickshaw pullers, cooks and other tradesmen, etc.

These are “informal sector” activities which are low paying. But, according to the ILO, the evidence suggests that the bulk of employment in the informal sector is economically efficient and profit-making. Thus such migrants earn enough to spend and remit to their homes.

Other migrants who are educated up to the secondary level find jobs as shophelpers, assistants, taxi drivers, repairing machines and consumer durables, marketing goods and in other informal activities that are small in scale, labour intensive and unregulated. Their earnings are sufficient to bring them in the category of a common urbanite with an income level higher than the unskilled workers.

Another class of migrants that is very small is of those who come for higher education in colleges and institutes to towns. They find good job in the “formal sector”, get good salaries, and follow a good standard of living. These are the persons who remit large sums to their homes and help in modernising the rural scenario.

(iii) Adverse Effects of Rural-Urban Migration:

Migration from rural to urban areas has a number of adverse effects. Towns and cities in which the migrants settle, face innumerable problems. There is the prolific growth of huge slums and shantytowns. These settlements and huge neighbourhoods have no access to municipal services such as clean and running water, public services, electricity, and sewage system.

There is acute housing shortage. The city transport system is unable the meet the demand of the growing population. There are air and noise pollutions, and increased crime and congestion. The costs of providing facilities are too high to be met, despite the best intentions of the local bodies.

Besides, there is massive underemployment and unemployment in towns and cities. Men and women are found selling bananas, groundnuts, balloons and other cheap products on pavements and in streets. Many work as shoeshines, parking helpers, porters, etc.

Thus, urban migration increases the growth rate of job seekers relative to its population growth, thereby raising urban supply of labour. On the demand side, there are no enough jobs available for the ruralities in the formal urban sector for the uneducated and unskilled rural migrants.

Consequently, this rapid increase in labour supply and the lack of demand for such labour lead to chronic and increasing urban unemployment and underemployment.

Patterns of Migration

Pattern 1. Inter-State Migration:

Inter-state migration is internal migration. When people from one state of a country move to another state in the same country for permanent settlement, it is called inter-state migration. The size of people migrating from one place to another is small in India.

In the Census of 1961, the registration of 68.6 per cent out of the total population was done at their birth place which shows that only 31.4 per cent people migrated. In the 1971 Census, this number decreased to 29.5 per cent.

Inter-state migration during 1961-71 shows that people from Uttar Pradesh, Kerala, West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Punjab, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Nagaland, Gujarat, Jammu & Kashmir and Bihar respectively migrated. Migration was continuously occurring in Maharashtra, Delhi, Madhya Pradesh, Assam and Gujarat.

During 1951-61 migration occurred from Jammu & Kashmir and Rajasthan, Bihar and Tamil Nadu to other states, while during 1961- 71, migration from other states occurred into these states. Thus, during 1951-61, these states were population losing states. During 1961-71, these states came under the category of population gaining states.

The inter-state migration data reveal that the highest population (6.41 per cent) migrated from other states to West Bengal in 1961 which is an industrially developed state, while the least people migrated to Jammu & Kashmir, which is a backward state. Similarly, the highest population (6.49 per cent) migrated to other states from Punjab; while the least population (0.98 per cent) migrated to other states from Assam.

During 1971-81, there were no important changes in the trends of migration. There was no significant change even in the size of population coming in Maharashtra from other states through migration. The highest population (3.7 per cent) migrated to Maharashtra from the northern states (Bihar, Punjab, etc.).

The migration stream from 1981 to 1991 shows that population from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, Punjab and Andhra Pradesh migrated mainly to Maharashtra, Bengal, Assam and Karnataka. In the inter-state migration, the role of female has been of much importance.

This is because females after their marriage settle at the place of their husbands. The marriage and migration rate being the same in almost all the states, no serious problem arises. People largely migrate to Delhi and other metropolitan cities because opportunities of employment, educational and other facilities are available there.

Pattern 2. Migrants by Place of Last Residence and Sex:

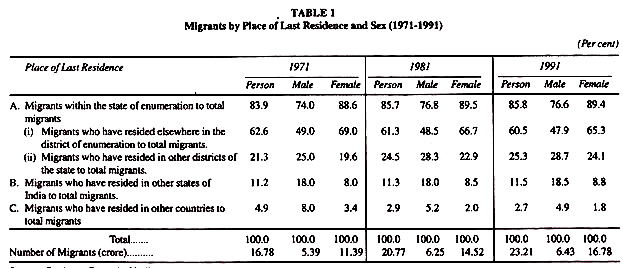

In India, the migrants by place of last residence and sex are shown in Table 1. The total number of migrants were 23.21 crores in 1991 which come to around 27 per cent of the Indian population. In sex-wise migration, the number of female migrants during 1971-91 due to socio-economic development in India, had increased by about 38 per cent.

The table reveals that most of the migration was short distance migration. This is because nearly 65 per cent of the migrants were enumerated in the same districts and nearly 90 per cent of the migrants were enumerated in the same state.

The table also shows the decrease in the international migration from 1971 to 1991. In 1971 the international migration accounted for 4.9 per cent of the total population while in 1991 it accounted for only 2.6 per cent of the total population.

The data for sex-wise migration by place of last residence indicates that females outnumbered males in the short distance migration, while males outnumbered females in the long distance migration.

Push Factor and Pull Factor of Migration

- Push factors:

- These factors force the people to move.

- These are negative factors associated with the current place or nation in which a person lives.

- Some of the push factors are worsening climate, unstable government and lack of job opportunities.

- Pull factors:

- These are certain positive factors associated with the new place, that people are moving into.

- Some of the pull factors are better standard of living, educational centres and better job opportunities.

Lees Theory of Migration

Everett Lee in his A Theory of Migration divides the factors that determine the decision to migrate and the process of migration into four categories:

1. Factors associated with the Area of Origin:

There are many factors which motivate people to leave their place of origin to outside area. They are push factors.

2. Factors associated with the Area of Destination:

There are very attractive forces at the area of destination to which the proportion of “selectivity” migrants is high. According to Lee, such forces are found in metropolitan areas of a country. Pull factors are present in such areas.

3. Intervening Obstacles:

There are intervening obstacles like distance and transportation which increase migrant selectivity of the area of destination. These obstacles have been lessened in modern times with technological advances. Lee also refers to cost of movements, ethnic barriers and personal factors as intervening obstacles.

4. Personal Factors:

Lastly, it is the personal factors on which the decision to migrate from the place of origin to the place of destination depends. In fact, it is an individual’s perception of the ‘pull and push forces’ which influence actual migration. He categorises these forces into “pluses” and “minuses” respectively. In other words, pluses are pull factors and minuses are push factors. In between them are “zeros” which balance the competing forces.

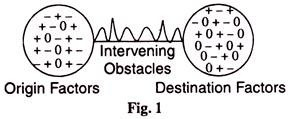

These are explained in Fig. 1, where the first circle represents the area of origin and the second circle the area of destination. The sign pluses represents the forces that attract people to a place (pull factors) and that of minuses represents the forces that push people from the area. Zeros represent the indifference of the people towards migration. In between these forces are the intervening obstacles.

According to Lee, it is the personal factors such as age, sex, race and education which alongwith the pull-push factors and intervening obstacles that determine migration. Further, there are sequential migrants such as children and wives of migrants who have little role in the decision to migrate.

Lee has formulated three hypotheses within the conceptual framework of the above noted four factors.

These are:

1. Characteristics of Migrants:

The following are the characteristics of migrants:

(1) Migration is selective.

(2) Migrants who respond primarily to plus factors at destination tend to be positively selective.

(3) Migrants who respond primarily to minus factors at origin tend to be negatively selective, or where they are overwhelming for the entire group, they may not be selective at all for migration.

(4) When all migrants are considered together selection for migration tends to be bimodel.

(5) The degree of positive selection increases with the difficulties of intervening obstacles.

(6) The characteristics of migrants tend to be intermediate between the characteristics of the population of the place of origin and those of place of destination.

(7) The higher propensity to migrate at certain stages of the life-cycle is important in the selection of migrants.

2. Volume of Migration:

The volume of migration is determined by the following factors:

(1) The volume of migration within a territory changes with the degree of areas included in it.

(2) It varies with the diversity of the people.

(3) It is related to the difficulty of evercoming the intervening variables.

(4) It varies with fluctuations in the economy.

(5) It varies with the state of progress in a country or area.

(6) Unless severe checks are imposed, both the volume and rate of migration tend to increase with time.

3. Streams and Counter-streams of Migration:

The following factors determine streams and counter-streams of migration:

(1) Migration tends to take place largely within well-defined streams.

(2) For every major migration stream, a counter-stream also develops.

(3) The efficiency of the stream and the counter- stream tends to be low if the place of origin and the place of destination are similar.