ECB 501

International Economics

Semester – V

Importance of International Economics

International economics refers to a field that focuses on the economic interactions between different countries. It aims to analyze various aspects of global economic activities, including trade, commerce, production, investment, migration, and the impact of these cross-border exchanges or transactions on the national economies.

It encompasses a wide range of topics and issues related to international trade, finance, and economic policy. The analysis of these relations between nations helps analysts, economists, businesses, and policymakers to predict its impact on micro and macro-economic levels. Moreover, the field of international economics continues to evolve as economic conditions change and new challenges emerge.

Key Takeaways- International economics is a branch of economics that deals with the economic interactions between nations across the globe. These include cross-border transactions, exchange, trade, and commerce.

- It includes globalization, trade policies, multinational corporations, foreign exchange, balance of payments, and economic collaborations between nations.

- Understanding this theory is crucial for policymakers, businesses, analysts, and economists. Hence, to navigate the complexities of the global economy and make sensible decisions in an interconnected world.

International Economics Explained

International economics refers to a branch of economics that examines the economic interactions and transactions occurring between countries. Its key characteristics include a global perspective, focusing on the cross-border exchange of goods, services, capital, and labor. Besides, the title “father of international economics” is often attributed to David Ricardo, a British economist who lived during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Moreover, it gauges the exchange rates and tariffs, exploring the factors that influence currency values and impact international trade and investments. Furthermore, it analyzes the impact of global events, like financial crises or pandemics, on national economies and international trade patterns.

A deep understanding of international economic concepts is essential for policymakers and economists to make well-informed decisions in the complex global marketplace.

However, the volatility of exchange rates, trade barriers such as tariffs and quotas, political instability affecting trade policies, economic imbalances between nations, currency risks due to fluctuations, regulatory differences, protection of intellectual property in foreign markets, and the increasing influence of environmental concerns such as sustainability and climate change are the critical factors in this regime. Managing these challenges demands a comprehensive understanding of international economics and the implementation of effective risk management strategies by businesses.

Additionally, international economics and finance are complementary fields that together provide an understanding of how countries interact economically on a global scale. They are crucial for policymakers, businesses, and investors as they navigate the complexities of the interconnected world economy. Thus, it provides insights into how countries can benefit from cooperation and efficient resource allocation to promote global economic growth and stability.

Components

International economics comprises the following key components, which are essential for analyzing the complexities of the global economy:

- Global Trade: International trade and commerce involves the study of the exchange of goods and services overseas, emphasizing concepts like comparative advantage and trade barriers.

- International Finance: This element focuses on the monetary and financial interactions between countries. Thus including aspects such as exchange rates, international monetary systems, and capital flows.

- Globalization: It refers to the integration of economies and societies worldwide through cross-border trade, investment, technology, and cultural exchange.

- Balance of Payments(BoP): BoP is a systematic record of a country’s economic transactions with the rest of the world. It includes trade balance, foreign direct investment (FDI), and foreign financial aid.

- Foreign Exchange Markets: The study of forex markets involves the trading of currencies and the determination of exchange rates between different currencies.

- Trade Policies: These are the policies implemented by governments. Therefore, to regulate international trade, encompassing measures like export-import tariffs, quotas, and trade agreements.

- Dependency Theory: As the development of a less-developed economy depends upon its interaction with a developed economy. Hence, it focuses on improving living standards in developing countries by understanding economic growth, poverty, and income distribution.

- International Organizations: Entities such as the World Bank, World Trade Organization (WTO), and International Monetary Fund (IMF) play significant roles in shaping international economic policies and providing financial assistance to countries.

- Multinational Corporations: These are large businesses that operate in multiple countries, facing challenges related to global supply chains, currency fluctuations, and international regulations.

Examples

Let us consider some cases where the study of international economics helps businesses, governments, and economists in decision-making:

Example #1

Suppose the US is a leading producer of advanced technology and electronics, while the UK specializes in the production of raw materials, such as minerals and metals. Recognizing their comparative advantages, the two nations engage in international trade. Hence, the US exports high-tech electronics to the UK, meeting the demand for sophisticated goods. In return, the UK exports raw materials vital for manufacturing to the US.

Therefore, this exchange benefits both nations; the US can access essential resources for its industries at a lower cost than if it attempted to produce them domestically, while the UK gains access to cutting-edge technologies it might not be able to develop on its own. The result is an efficient allocation of resources, economic growth, and an enhanced standard of living for the citizens of both countries, underscoring the mutual benefits derived from international economic cooperation and specialization.

Example #2 – IMF’s SDR Boosts Global Economy

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) made its largest-ever allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) in August 2021, injecting $650 billion into countries to aid pandemic recovery. SDRs are reserve assets used to safeguard global stability; they can be saved, exchanged for currencies, or spent on various needs, including vaccines and social assistance.

A recent study shows the 2021 allocation met its objectives, benefiting all IMF members, predominantly low-income countries. G20 countries pledged over $100 billion of SDRs to support vulnerable nations, enhancing the allocation’s impact. Low-income countries received double the allocation compared to advanced economies, strengthening their international reserves.

Moreover, SDRs helped countries lower borrowing costs, enabling them to address urgent needs like healthcare and vaccines. Governments used SDRs responsibly, saving them for future shocks, spending on critical needs, and ensuring transparency. While interest costs have risen due to higher global rates, SDRs remain a cost-effective financing option.

Hence, international economics must evaluate future SDR allocations carefully, considering higher interest and inflation rates. Stronger economies need to fulfill their pledges, supporting vulnerable countries facing multiple challenges. SDRs are valuable but not a standalone solution, complementing broader support measures provided by the IMF, including policy advice, financial support, and technical assistance.

Importance

International economics is indispensable for shaping global economic policies and encouraging international cooperation. Its significance lies in the following points:

- Global Interconnectedness: In today’s world, economies are highly interconnected. Understanding international economics helps in comprehending the complexities of global trade, finance, and investment, which are essential aspects of the modern economy.

- Trade and Development: It fosters economic growth and development by allowing countries to specialize in what they do best and exchange goods and services with others. It helps in creating jobs, increasing income, and improving living standards.

- Policy Formulation: Policymakers rely on international economics principles to make informed choices about tariffs, trade agreements, foreign aid, and other economic policies, considering their far-reaching consequences on their economies and the world.

- Currency Exchange: The study of exchange rates is crucial for businesses and governments since fluctuations in exchange rates impact trade balances, inflation rates, and overall economic stability.

- Cultural Exchange: It fosters cultural exchange by encouraging the flow of ideas, traditions, and lifestyles between trading nations, leading to mutual understanding and tolerance.

- Investment Opportunities: Understanding international interaction trends and scope helps investors assess opportunities and risks in different countries, enabling them to make informed investment decisions.

- Fosters International Trade: A fundamental aspect of international economics, promotes economic growth by facilitating the exchange of goods and services between nations.

- Comparative Advantage and Resource Allocation: It encourages specialization in cross-border transactions, allowing countries to trade products efficiently and allocate resources effectively on a global scale.

- Global Development: It provides insights into how countries, especially developing ones, can integrate into the global economy, attract investments, and improve their living standards.

- Global Financial Stability: It also contributes to the viability and stability of the global financial and economic system by analyzing financial crises, capital flows, and the impact of policies across borders.

Inter-Regional and International Trade

Nevertheless, there are several reasons to believe the classical view that international trade is fundamentally different from inter-regional trade.

1. Factor Immobility:

The classical economists advocated a separate theory of international trade on the ground that factors of production are freely mobile within each region as between places and occupations and immobile between countries entering into international trade. Thus, labour and capital are regarded as immobile between countries while they are perfectly mobile within a country.

There is complete adjustment to wage differences and factor-price disparities within a country with quick and easy movement of labour and other factors from low return to high sectors. But no such movements are possible internationally. Price changes lead to movement of goods between countries rather than factors. The reasons for international immobility of labour are—difference in languages, customs, occupational skills, unwillingness to leave familiar surroundings, and family ties, the high travelling expenses to the foreign country, and restrictions imposed by the foreign country on labour immigration.

The international mobility of capital is restricted not by transport costs but by the difficulties of legal redress, political uncertainty, ignorance of the prospects of investment in a foreign country, imperfections of the banking system, instability of foreign currencies, mistrust of the foreigners, etc. Thus, widespread legal and other restrictions exist in the movement of labour and capital between countries. But such problems do not arise in the case of inter-regional trade.

2. Differences in Natural Resources:

Different countries are endowed with different types of natural resources. Hence they tend to specialise in production of those commodities in which they are richly endowed and trade them with others where such resources are scarce. In Australia, land is in abundance but labour and capital are relatively scarce. On the contrary, capital is relatively abundant and cheap in England while land is scarce and dear there.

Thus, commodities requiring more capital, such as manufactures, can be produced in England; while such commodities as wool, mutton, wheat, etc. requiring more land can be produced in Australia. Thus both countries can trade each other’s commodities on the basis of comparative cost differences in the production of different commodities.

3. Geographical and Climatic Differences:

Every country cannot produce all the commodities due to geographical and climatic conditions, except at possibly prohibitive costs. For instance, Brazil has favourable climate geographical conditions for the production of coffee; Bangladesh for jute; Cuba for beet sugar; etc. So countries having climatic and geographical advantages specialise in the production of particular commodities and trade them with others.

4. Different Markets:

International markets are separated by difference in languages, usages, habits, tastes, fashions etc. Even the systems of weights and measures and pattern and styles in machinery and equipment differ from country to country. For instance, British railway engines and freight cars are basically different from those in France or in the United States.

Thus goods which may be traded within regions may not be sold in other countries. That is why, in great many cases, products to be sold in foreign countries are especially designed to confirm to the national characteristics of that country. Similarly, in India right-hand driven cars are used whereas in Europe and America left-hand driven cars are used.

5. Mobility of Goods:

There is also the difference in the mobility of goods between inter-regional and international markets. The mobility of goods within a country is restricted by only geographical distances and transportation costs. But there are many tariff and non-tariff barriers on the movement of goods between countries. Besides export and import duties, there are quotas, VES, exchange controls, export subsidies, dumping, etc. which restrict the mobility of goods at international plane.

6. Different Currencies:

The principal difference between inter-regional and international trade lids in use of different currencies in foreign trade, but the same currency in domestic trade. Rupee is accepted throughout India from the North to the South and from the East to the West, but if we cross over to Nepal or Pakistan, we must convert our rupee into their rupee to buy goods and services there.

It is not the differences in currencies alone that are important in international trade, but changes in their relative values. Every time a change occurs in the value of one currency in terms of another, a number of economic problems arise. “Calculation and execution of monetary exchange transactions incidental to international trading constitute costs and risks of a kind that are not ordinarily involved in domestic trade.”

Further, currencies of some countries like the American dollar, the British pound the Euro and Japanese yen, are more widely used in international transactions, while others are almost inconvertible. Such tendencies tend to create more economic problems at the international plane. Moreover, different countries follow different monetary and foreign exchange policies which affect the supply of exports or the demand for imports. “It is this difference in policies rather than the existence of different national currencies which distinguishes foreign trade from domestic trade,” according to Kindleberger.

7. Problem of Balance of Payments:

Another important point which distinguishes international trade from inter-regional trade is the problem of balance of payments. The problem of balance of payments is perpetual in international trade while regions within a country have no such problem. This is because there is greater mobility of capital within regions than between countries.

Further, the policies which a country chooses to correct its disequilibrium in the balance of payments may give rise to a number of other problems. If it adopts deflation or devaluation or restrictions on imports or the movement of currency, they create further problems. But such problems do not arise in the case of inter-regional trade.

8. Different Transport Costs:

Trade between countries involves high transport costs as against inter- regionally within a country because of geographical distances between different countries.

9. Different Economic Environment:

Countries differ in their economic environment which affects their trade relations. The legal framework, institutional set-up, monetary, fiscal and commercial policies, factor endowments, production techniques, nature of products, etc. differ between countries. But there is no much difference in the economic environment within a country.

10. Different Political Groups:

A significant distinction between inter-regional and international trade is that all regions within a country belong to one political unit while different countries have different political units. Inter-regional trade is among people belonging to the same country even though they may differ on the basis of castes, creeds, religions, tastes or customs.

They have a sense of belonging to one nation and their loyalty to the region is secondary. The government is also interested more in the welfare of its nationals belonging to different regions. But in international trade there is no cohesion among nations and every country trades with other countries in its own interests and often to the detriment of others. As remarked by Friedrich List, “Domestic trade is among us, international trade is between us and them.”

11. Different National Policies:

Another difference between inter-regional and international trade arises from the fact that policies relating to commerce, trade, taxation, etc. are the same within a country. But in international trade there are artificial barriers in the form of quotas, import duties, tariffs, exchange controls, etc. on the movement of goods and services from one country to another.

Sometimes, restrictions are more subtle. They take the form of elaborate custom procedures, packing requirements, etc. Such restrictions are not found in inter-regional trade to impede the flow of goods between regions. Under these circumstances, the internal economic policies relating to taxation, commerce, money, incomes, etc. would be different from what they would be under a policy of free trade.

Conclusion:

Therefore, the classical economists asserted on the basis of the above arguments that international trade was fundamentally different from domestic or inter-regional trade. Hence, they evolved a separate theory for international trade based on the principle of comparative cost differences.

Pure Theory of International Trade

The Pure Theory of International Trade, also known as the classical theory of international trade, is a body of economic thought that seeks to explain the patterns and benefits of international trade. Developed by classical economists such as David Ricardo and Adam Smith, this theory is foundational to the understanding of how countries engage in trade and specialize in the production of certain goods and services.

1. Comparative Advantage:

The cornerstone of the Pure Theory of International Trade is the principle of comparative advantage. David Ricardo introduced this concept in his seminal work, “Principles of Political Economy and Taxation” (1817). Comparative advantage suggests that even if a country is less efficient in the production of all goods compared to another country, it can still benefit from specializing in the production of the goods in which it has a lower opportunity cost.

2. Opportunity Cost:

Opportunity cost is a fundamental concept in the Pure Theory of International Trade. It refers to the value of the next best alternative forgone when a choice is made. In the context of international trade, countries should specialize in producing goods and services where their opportunity cost is relatively lower than that of other countries.

3. Absolute Advantage:

While comparative advantage focuses on relative efficiency, absolute advantage, another concept introduced by Adam Smith, looks at the absolute productivity of a country in producing a good or service. A country has an absolute advantage if it can produce a good with fewer resources than another country. However, Ricardo argued that comparative advantage is a more relevant concept for analyzing international trade.

4. Gains from Trade:

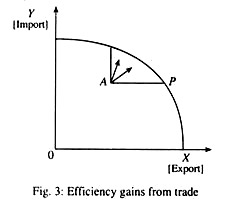

The Pure Theory of International Trade asserts that all trading partners can benefit from trade, even if one country has an absolute advantage in the production of all goods. By specializing in the production of goods in which they have a comparative advantage and trading with other nations, countries can increase their overall consumption and achieve higher levels of economic welfare.

5. Factor Proportions and Factor Price Equalization:

The theory extends to factors of production, such as labor and capital. Countries are expected to export goods that intensively use their abundant factor and import goods that intensively use their scarce factor. Over time, international trade is expected to equalize factor prices among trading nations.

6. Assumptions and Limitations:

The Pure Theory of International Trade makes several assumptions, including perfect competition, constant returns to scale, and the immobility of factors of production between countries. Critics argue that these assumptions limit the applicability of the theory to real-world situations, where conditions may be more complex.

7. Extensions and Modern Developments:

The Heckscher-Ohlin model and the New Trade Theory are extensions of the Pure Theory that consider factors such as factor endowments, factor mobility, and economies of scale. These models aim to provide a more nuanced understanding of international trade patterns in a globalized world.

8. Policy Implications:

The Pure Theory of International Trade has implications for trade policy. It suggests that protectionist measures, such as tariffs and quotas, may hinder the realization of gains from trade. Free trade is generally advocated as a policy that promotes economic efficiency and welfare.

Conclusion:

The Pure Theory of International Trade remains a foundational framework for understanding the patterns and benefits of international trade. While it has been extended and modified over time to address the complexities of the global economy, the core principles of comparative advantage and gains from trade continue to be influential in the field of international economics. However, it’s important to recognize that the real-world application of these theories involves numerous additional factors and considerations beyond the simplified assumptions of the pure theory.

Absolute and Comparative Advantages

Absolute advantage and comparative advantage are concepts that relate to international trade and economics. These economic policies can help determine how countries, companies or businesses choose to manufacture and trade for products. These two concepts influence decisions made by entities to commit natural resources and labor to produce specific goods.

Key takeaways:The concepts of absolute and comparative advantages help countries and businesses assess product values and determine international trade options.

Absolute advantage evaluates how efficiently a single product can be produced for quality, quantity and profit.

Comparative advantage helps an entity select between several products to determine which has the greater return.

What is absolute advantage?

Economists use the term absolute advantage to explain how an entity can manufacture a better product at a faster rate and with greater profit than one produced by a competing country or business. An absolute advantage assessment evaluates the efficiency of creating a single product, helping the entity avoid producing goods with little to no demand or profit. Whether the entity has an absolute advantage in that field may play a role in determining what its leaders decide to produce.

Example: If Germany and France both produce automobile engines, business analysts identify which country has the best manufacturing results according to time, quality and profit. If Germany produces high-quality engines at a faster rate and with a greater profit, it has an absolute advantage in that particular industry. As a result, France might consider allocating funds and labor to other industries, such as motorcycle engine manufacturing, where it may have the absolute advantage.

What is comparative advantage?

Comparative advantage evaluates a business, company or nation’s ability to manufacture a product according to profit and cost, but it also takes into consideration the opportunity costs involved with choosing to produce a variety of goods with limited resources. Opportunity costs involve the benefits — mainly profits — that an entity loses when choosing one option over another.

Example: Italy has enough resources to produce 100,000 bottles each of red and white wines. If the white wine sells for $100 a bottle and the red wine for $50 a bottle, the white wine generates a higher profit at $100 a bottle compared to $50 for a bottle of red wine. The opportunity cost is the value lost by producing more red wine than white. The comparative advantage indicates that if Italy had to choose between producing white or red wine, white is the better choice.

Absolute vs. comparative advantage

The concepts of absolute advantage and comparative advantage help international trade professionals determine the best choices regarding domestic production of goods, imports and exports and resource allocation. While the absolute advantage refers to one entity’s superior production capabilities vs. another’s in a single industry, comparative advantages also consider lowering opportunity costs.

Understanding the differences between absolute advantage and comparative advantage can help you know when it may be appropriate to use one or the other. Key differences between absolute and comparative advantage include:

Trade benefits

Professionals who work in international trade use comparative advantage assessments to determine which country might produce a product for the lowest opportunity cost (value lost), thus having a higher comparative advantage versus its closest competitors. Calculating comparative advantage may encourage countries to consider trading with one another, which can have positive effects for all involved.

While entities that have an abundance of a product may have the absolute advantage in that industry, they may not have a comparative advantage. For example, If an entity had the absolute advantage for oil but had no bodies of water for fishing and a neighboring entity agreed to trade oil for fish, the country with oil would have the comparative advantage with oil. The entity with many bodies of water would have a comparative advantage for fishing. Ultimately, both countries would gain something from the trade relationship. Here’s an example of this:

Example: Suppose Italy holds a lower opportunity cost for white wine while Spain has the lowest opportunity cost for red wine. If the two countries engage in the wine trade, it could create job opportunities and help to diversify labor forces by introducing new professional roles while maximizing the absolute advantage of their respective products.

Production specialization

A comparative advantage encourages entities to allocate their resources to specialize in areas where they may have the lowest opportunity costs and therefore manufacture and produce products at a lower cost than other goods.

An absolute advantage encourages specialization in an area where the entity exhibits exceptional production capabilities regarding the quality of the product and the total manufacturing time. While comparative advantage encourages specialization in relation to production costs and comparative advantages of other nations, absolute advantage emphasizes specialization in an industry where an entity is ultimately superior.

Production costs

Production costs can include employee wages, materials, factory maintenance and shipping expenses. International trade professionals calculate both absolute advantages and comparative advantages to help determine which entity offers the lowest production costs for the highest profit. However, when determining a comparative advantage, they also take opportunity cost into account.

Absolute advantage refers to lowering production cost whereas comparative advantage refers to lowering opportunity cost to sell goods and services at prices lower than competitors, yielding greater profitability and stronger sales margins. With comparative advantage, an entity shows lower opportunity cost, but may not produce goods at a higher quality or increased volume.

Economic effectiveness

Calculating a comparative advantage tells economists and financial professionals which production option offers a more economically effective solution. This is because the concept of absolute advantage concentrates mainly on maximizing production with the same resources available without accounting for the possibility of cost reduction.

Alternatively, the concept of comparative advantage helps entities find the lowest-cost option for all involved. Comparative advantage also encourages resource reallocation and import-export relationships between entities, improving the monetary return of all entities involved.

Reciprocal Demand and Opportunity Cost (Haberler)

Haberler has reformulated the doctrine of comparative costs in terms of opportunity costs.

According to Haberler, the ratio of prices in each country in isolation is a reflection not only of the money costs of production but more fundamentally of social opportunity costs.

Opportunity cost refers to the cost of a commodity in terms of other commodity which must be foregone in order to obtain the first.

With the assumptions of:

(i) Perfect competition in product and factor markets,

(ii) Absence of external economies and diseconomies,

(iii) Given supply of factors of production,

(iv) Fully employed factors and

(v) Given technological knowledge, an increase in the output of any commodity is necessarily at the expense of a smaller production of one or more other commodities, since the increase in the production of the first commodity can be effected only by transferring productive factors out of their present employment in other lines. The other commodities not produced but could have been produced with the factors which have been used up in product is its social opportunity cost.

Let us see how opportunity costs can explain the basis of and gains from trade. Plow how this doctrine of opportunity cost is used to explain the comparative advantage in trade theory. For example, in country I, the price and cost of production of one unit of good X is Rs. 2 and that of Y is Re 1; this means that the opportunity cost of an extra unit of X is two units of Y. This is how money cost reflects the opportunity cost. Mow under competition, the price of each factor is equal to the value of its marginal product and is the same in all alternative occupations. The factors required to produce one unit of Y1 therefore, could produce one rupee’s worth of X if transferred to that employment.

Therefore, in our example, one unit of X requires two rupees worth of productive services, so that two units of Y must be given upto acquire on extra unit of X.

Cost of production:

Country I

I unit of X = Rs. 2

1 unit of Y = Re. 1

1 unit of X = 2 units of Y.

Now in another country, for example, II, the opportunity cost of an extra unit of X is three of Y. If, as in the example given above, the price cost ratio and therefore the opportunity costs are different, trade will take place.

Cost of production:

Country II

1 unit of X = Rs. 3

1 unit of Y = Re. 1

1 unit of X = 3 units of Y.

The terms of trade must fall between the price cost ratios of the two countries in isolation, the exact point being determined by the reciprocal demand for each other products in conjunction with cost conditions. Suppose, the terms of trade is one unit of X=2.5 units of Y. Domestically, people of country I are able to obtain only 2 units of Y per one unit of X given up (not produced at home); with trade they obtain two and a half units of Y per unit of X given up (produced but exported). In country II, without trade each unit of X produced involve the sacrifice of three units of Y; with trade they obtain X at a rate of two and a half units of Y per X. Each country has a greater volume of goods available to it as a result of trade. Thus,

‘The opportunity cost doctrine can be made a basis to explain the comparative advantage and gains from trade.”

It is obvious that in this new approach there is no further need of the much controversial labour theory of value.

Its superiority lies in the fact that it directly admits the relevance of more than one factor and the different combinations of these factors to the problem of relative values. Haberler concludes that “it is now the general practice to apply either the concept of opportunity costs or the modern theory of general equilibrium to the problem of international trade. Basically there is no contradiction between these two methods.

The doctrine of opportunity costs when carried sufficiently beyond the initial simplifying assumptions and elaborated more fully merges into the theory of general equilibrium. The former theory can thus be looked upon as a somewhat simplified version of the later, designed for easy presentation and practical use.”

Joint credit for developing the modern simplified general equilibrium theory of trade had frequently been split between Heckscher-Ohlin on the one hand, and Haberler on the other. Haberler’s “opportunity costs” exposition essentially breaks into the general economic equilibrium at an intermediate point. Accepting certain assumptions about the system, we can conclude that the unit money costs of production of a commodity are equal to the value of commodities whose production is forgone in order to produce it.

Samuelson says, ‘when stated with full qualifications, the doctrine of opportunity costs inevitably degenerates into the conditions of general equilibrium.”

It has been commonly believed that the major source of difference between Haberler’s transformation curve geometry and Ohlin’s general equilibrium model is that the former is incapable of taking into account changes in the quantities of factors supplied. This limitation is implied in Viner’s extensive attack on the opportunity cost theory of value which underlies Haberler’s model. Viner’s attack is phrased in welfare terms, and really boils down to the claim that the opportunity cost interpretation is inferior as a tool of welfare evaluation to the real cost approach of the classical economists.

Heckscher-Ohlin Theory

Introduction

The post-World War II global economy is better characterised by the Heckscher-Ohlin (HO) model. It is predicated on the idea that trading nations will use similar production technology. Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin, two Swedish economists, had the original idea in 1919. According to the Heckscher-Ohlin model of economics, nations should export the goods and services they can create most effectively and in large quantities. It is also known as the H-O model or the 2x2x2 model, and it is used to assess trade, particularly, the equilibrium of trade between two nations with different skills and natural resources. According to the theory, which is a comparative advantage theory in economics, nations with relatively abundant capital and relatively insufficient labour will tend to export capital-intensive goods and import labour-intensive ones, whereas nations with relatively abundant labour and relatively insufficient capital will tend to export labour-intensive goods and import capital-intensive ones. The export of commodities requiring abundantly available production inputs is emphasised by the model. This article discusses the Heckscher-Ohlin theory of international trade in detail.

What is the Heckscher-Ohlin theory of international trade

According to the Heckscher-Ohlin theory, what matters is the amount of capital per worker rather than the total amount of capital. A small nation like Luxembourg has more capital per worker than India, but has far less capital overall. Therefore, according to the Heckscher-Ohlin theory, Luxembourg will export capital-intensive goods to India and purchase labour-intensive goods in exchange.

In 1919, Eli Heckscher of the Stockholm School of Economics published a study in Sweden that served as the foundation for the Heckscher-Ohlin model. Further, in 1933, Bertil Ohlin, one of his students, contributed to it. Practical implementation of this theory can be seen, for instance, in the fact that some nations have significant oil deposits but very little iron ore. Other nations, however, have little in the way of agricultural production despite having easy access to and storage for precious metals. For instance, the Netherlands exported over $577 million in U.S. dollars in 2019 compared to imports of roughly $515 million in that same year. Germany was its principal import-export partner. It was able to manufacture and supply its products more successfully and economically by importing on a nearly comparable scale.

Paul Samuelson, an economist, developed the initial framework in essays published in 1949 and 1953. For this reason, some call it the Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson model. The Heckscher-Ohlin model provides a mathematical explanation of how a nation should manage its resources and conduct international trade. It identifies the desired equilibrium between two nations, each with their own resources.

The factor endowment hypothesis was created and expanded upon by Heckscher’s pupil, Bertil Ohlin. In addition to teaching economics at Stockholm University, he was also a prominent politician in Sweden. He served in the Swedish parliament, the Riksdag, and led the liberal party for nearly 25 years. He served as the trade minister during World War II. Ohlin and James Meade shared the 1979 Nobel Prize for economics for their contributions to the theory of international commerce.

The model is not constrained to trade goods. It also takes into account additional production factors, such as labour. According to the model, as labour prices differ from country to country, those with inexpensive labour forces should concentrate primarily on creating items that require a lot of labour. Even though the Heckscher-Ohlin model seems plausible, most economists have had trouble locating supporting data. Other models have been proposed to explain why industrialised and developed nations have historically tended to trade more with one another and less with developing nations.

History behind the Heckscher Ohlin theory of international trade

- Since 1933, the Heckscher-Ohlin model has been a particularly popular hypothesis of global trade. Since then, a large number of economists have examined the theory’s applicability to statistics on global commerce. Wassily Leontief conducted the most well-known test. To assess whether the United States was exporting capital-intensive items and importing labour-intensive goods as the theory would suggest, Leontief examined trade statistics from 1947. He made use of input/output tables for replacing American exports and imports. Leontief divided the 200 industries into 50 sectors.

- He came to the conclusion that America was actually exporting labour-intensive items rather than capital-intensive ones in 1947 because he discovered that exports were 30% more labour-intensive than import alternatives. It was completely at odds with how people had perceived America’s capital endowments. He was the first to empirically examine the Heckscher-Ohlin model and his findings contradicted the model itself.

- Despite Leontief’s findings, the Heckscher-Ohlin model continued to be a significant contribution to the discipline for the following three decades. Still, economists held that the endowments of various nations had to affect commerce. People eventually began referring to his discoveries as the Leontief Paradox. This new conundrum sparked a number of additional testing of the H-O model by other economists as well as explanations for why the theorem failed.

- According to Leontief, the United States actually has an abundance of workers because its labour productivity is three times higher than that of the rest of the world. Tests in subsequent years revealed that the paradox had diminished. Here are a few justifications for the Leontief Paradox:

- Leontief actually made an attempt to resolve the dilemma by claiming that American workers were more productive than those from other countries. Due to this, the United States exported items that required labour as opposed to goods that required capital.

- The topic of tariffs and transportation expenses was brought up as an additional justification. W.P. Travis suggested that the Leontief Paradox may have been brought on by tariffs. Then it was determined that only the volume of trade is truly impacted by tariffs rather than the flow. The fact that Leontief neglected to account for human capital is another factor that has been cited as a source of the conundrum. Resources, time, and investment are all required for human capital. The outcomes of his studies would have been significantly altered had he included human capital in the model.

- Using trade statistics from 1962, Robert Baldwin discovered that American imports required 27% more capital than an American export. Tatemoto and Ichimura conducted a test in the 1950s, when Japan was a labour-rich nation, and discovered that the country’s overall trade did not follow the H-O model.

- Japan purchased labour-intensive items while exporting capital-intensive ones. They discovered that it was consistent with the H-O model when they tested solely the Japanese and American commerce. Baldwin investigated India’s global trading patterns. He discovered that India’s exports required a lot of labour, which was in line with the Heckscher-Ohlin theory. He discovered that India was exporting capital-intensive commodities and buying labour-intensive goods when he used his criteria on merely trade between the two countries. This contradicts the H-O model.

Components of the Heckscher Ohlin model

The Heckscher-Ohlin-Vanek Theorem, which forecasts the factor content of commerce, has garnered attention recently. This is because it is challenging to predict the patterns of trade in a world with many different items. There are four major components of the Heckscher-Ohlin model:

Stolper-Samuelson Theorem

- The Stolper-Samuelson Theorem, which was created by these two authors, is based on the following key presumptions:

- One of the two trade nations under consideration for the analysis solely manufactures steel and fabric and uses labour and capital as its only two inputs.

- The first-degree homogeneity of the production functions for the two commodities is present. It suggests that consistent returns to scale control production.

- Capital and labour are both fully used.

- The availability of the two production factors is fixed.

- Both the product and factor markets meet the requirements for perfect competition.

- The given nation has a surplus of labour but a shortage of capital.

- Steel is a capital-intensive good, whereas cloth is a labour-intensive good.

- The rules governing international trade are set.

- Neither good serves as an input in the manufacture of the other good.

- Although both criteria are transferable across two businesses or sectors, they are not transferable between two nations.

- There are no transportation expenses.

- According to the Stolper-Samuelson theory, a country with two commodities and two factors will see a greater than proportionate increase in the price of the associated “intense” factor. On the other hand, Rybczynski establishes the hypothesis that, in a country with two commodities and two productive factors, an increase in the labour force combined with a constant aggregate endowment of the other productive factor leads to an actual decline in the total output of the other commodity and a greater than proportionate increase in the output of the labour-intensive commodity when the terms of trade are held constant.

- The Stolper-Samuelson Theorem leads to some important implications that has been laid down hereunder:

Increase in welfare

Trade results in an improvement in the welfare of the production component that is heavily utilised in the growing industry at the expense of the scarce factor. Overall, there has been a net improvement in the community’s welfare.

A better income distribution

Trade increases the proportion of plentiful factors in the GNP (Gross National Product), which improves the equity of income distribution.

Promotional export strategy

The theory has a significant policy application in that it suggests that export promotion, as opposed to import substitution, is a better strategy for achieving development and equal income distribution in less developed nations.

Impact of tariffs and other protective measures

According to the theorem, imposing tariffs and other punitive or protective measures will result in a decrease in imports. That will also reduce the chances of increasing exports. It will continue to keep the abundant factor’s real income at a lower level than the scarcity factor’s. The growth process will be halted as a result, and the income distribution will become unfair.

- By authors like Kelvin Lancaster, Lloyd Metzler, and Jagdish Bhagwati, the Stolper-Samuelson Theorem was eventually questioned, altered, and expanded. Metzler abandoned the idea of fixed terms of trade and proposed that, given an inelastic offer curve from a foreign country, the imposition of a tariff would result in an improvement in the terms of trade of the country imposing the tariff through an increase in the internal price of the country’s export and a decrease in the internal price of the country’s import. As a result, fewer import alternatives will be produced, and money will be allocated so that it benefits the factor that is utilised more frequently in the manufacturing of exportable goods. The idea that protection would lead to an unfair income distribution was rejected by Kelvin Lancaster. Jagdish Bhagwati disagreed with the theorem’s general applicability. He talked about potential alternate consequences of protection on the wages of more heavily employed workers. The author wrote that “protection (prohibitive or otherwise) will raise, reduce, or leave unchanged the real wage of the factor intensity employed in the production of goods according to protection raises, lowers, or leaves unchanged the relative price of that good”.

Rybczynski Theorem

- Tadeusz Rybczynski (1923–1998), an economist who was born in Poland, created the Rybczynski theorem in 1955. According to this, at stable relative goods prices, an increase in the endowment of one component will result in an absolute decrease in the output of the other good and a more than proportional expansion of the output in the sector that employs that factor heavily.

- According to the Rybczynski theorem, there is a direct correlation between changes in a factor’s endowment and changes in the output of a product that heavily depends on that factor. According to the Rybczynski theorem, changes in a factor’s endowment have a negative impact on the output of a product that does not heavily utilise that factor.

- When full employment is maintained, the Rybczynski theorem illustrates how changes in an endowment impact the outputs of products. In the context of a Heckscher-Ohlin model, the theorem is helpful in examining the consequences of capital investment, immigration, and emigration.

- Open commerce between two regions frequently results in changes in the relative factor supply between the regions, according to the Heckscher-Ohlin model of international trade. The amounts and types of outputs between the two regions may change as a result. The Rybczynski theorem explains both the results of an increase in the supply of one of these factors and the impact on the output of an item whose production is dependent on the opposite element.

- The Heckscher-Ohlin model’s most basic iteration, the Rybczynski theorem implies that two items, like automobiles and textiles, are produced utilising the same two-factor inputs, such as labour and capital, but in different proportions depending on the industry. The auto business is said to be a capital-intensive industry if it employs a larger capital-to-labour ratio than the textile industry, which is referred to as a labour-intensive industry. The production possibility frontier moves outward when either factor’s supply rises while keeping the other’s supply constant, according to the model’s normal assumptions. As a result, the economy can now produce more of both goods. Prior to Rybczynski’s contribution, the majority of economists assumed that this type of biassed growth would lead to higher equilibrium outputs of each good, though with relatively greater growth of the industry that uses more of the growth factor.

Heckscher-Ohlin Trade Theorem

- The traditional comparative cost theory was unable to adequately explain why the comparative costs of producing different goods varied between nations. The novel hypothesis put out by Heckscher and Ohlin probed the fundamental factors that influence variations in comparative costs. They clarified that the disparities in comparative costs are due to variances in the factor endowments of various countries and the various factor ratios required to produce various commodities. Therefore, the Heckscher-Ohlin theory of international trade is the name given to this novel theory.

- Heckscher and Ohlin’s explanation of international commerce is widely accepted among contemporary economists, hence the theory is also known as the modern theory of international trade. Additionally, this theory is often referred to as the General Equilibrium Theory of International Trade because it is based on a general equilibrium analysis of price setting. It is important to note that Ohlin claims there is no fundamental distinction between domestic (inter-regional) and international trade, in contrast to the perspective of classical economics. He is correct in saying that inter-regional trade is only a specific case of international trade.

- Ohlin argues that while transportation costs are included in domestic inter-regional trade, they do not serve as a defining factor in separating domestic trade from international trade. Trade is possible because the value or purchasing power of different currencies is determined by their relationship to one another through foreign exchange rates.

Factor Price Equalisation Theorem

- The factor-price equalisation theorem is the fourth significant theorem that results from the Heckscher-Ohlin model. The theorem simply states that as countries transition to free trade and the prices of the output goods are equalised between them, the prices of the factors (labour and capital) will also be equalised.

- The implication is that free trade will globally equalise both worker salaries and capital rents. The model’s most crucial premise that the two nations have the same manufacturing technology and that markets are perfectly competitive is where the theorem stems from.

- The value of a factor of production’s marginal productivity determines the return on investment in a market with perfect competition. The amount of labour being employed and the amount of capital both affect a factor’s marginal productivity, such as labour. The marginal productivity of labour decreases as the amount of labour in a certain industry increases. The marginal productivity of labour increases as capital increases.

- Finally, the output price that the good in the market commands determines the value of productivity. In autarky, the pricing for the output goods is different in the two nations. Because it influences marginal productivity, a difference in pricing alone can lead to variations in wages and rents between nations. The variance in wages and rents, however, also has an impact on the capital-labour ratios in each industry, which in turn has an impact on the marginal products, in a variable proportions model.

- All of this indicates that the wage and rental rates will vary between nations in autarky for a variety of reasons.

- The two nations’ production prices will be equal once unrestricted trade in goods is permitted. Since the marginal productivity relationships between the two countries are the same, only one set of wage and rental rates can fulfil these relationships for a certain set of output prices. As a result, free trade will equalise the cost of commodities as well as wage and rent rates.

- Both nations will use the same capital-labour ratio to create each good because they have the same salary and rental costs. However, the countries will generate different amounts of the two things since they continue to have differing amounts of factor endowments.

- In contrast to the Ricardian model, this outcome states that the two nations’ production technologies are thought to differ. Real wages continue to differ between nations even after they adopt free trade as a result; the nation with the highest productivity will have higher real wages.

- It might be challenging to determine whether production technologies are unique, comparable, or distinct in the actual world. One could contend that cutting-edge capital can be sent anywhere in the world if equivalent industrial technology is used. On the other hand, one may argue that just because two pieces of equipment are comparable, it doesn’t necessarily follow that the workforce will use it in the same way. Differences in organisational skills, work habits, and incentives will probably always exist.

- One way to translate these model results into reality is to claim that, to the degree that nations have comparable production capacities, factor prices will tend to converge as freer trade is achieved.

Purposes of the Heckscher Ohlin theory of international trade

The approach emphasises how when each nation makes the greatest effort to export commodities that are domestically naturally abundant, everyone benefits globally and through international trade. When nations import the resources they lack natively, everyone wins. A country can benefit from elastic demand since it need not rely entirely on domestic markets. As additional nations and new markets grow, labour costs rise and marginal productivity falls. Trading globally enables nations to adapt to capital-intensive manufacturing, which would be impossible if each nation exclusively sold goods domestically.

Additionally, it highlights the importation of items that a country cannot produce as effectively. It advocates for nations to export commodities and resources they have an excess of while proportionately importing those resources they require. Some nations have a relatively high level of capital, which means that the average worker has access to a wide range of tools and machines to help with the job. These nations typically have high pay rates, which makes it more expensive to produce labour-intensive commodities like textiles, sporting goods, and basic consumer electronics than it would be in nations where there is a surplus of labour and low wage rates.

Conversely, in nations with cheap and abundant capital, items like automobiles and chemicals that require a lot of capital but little labour tend to be relatively inexpensive. Therefore, nations with a lot of capital should be able to create capital-intensive commodities fairly cheaply and export them to cover the cost of importing goods that require a lot of labour.

Assumptions made by the Heckscher Ohlin theory of international trade about the world economy

The seven assumptions that were put forth by the Heckscher Ohlin theory of international trade about world economy have been listed hereunder:

- Consumers deal with the same preferences and consumption functions;

- All nations use the same production technology;

- While the marginal returns to any one factor are declining, the output yields constant returns to scale;

- The technical costs of capital and labour per unit differ between the items;

- Perfect competition is the foundation of the markets;

- There are no restrictions on foreign trade; and

- The availability of resources is fixed to a certain degree and is the same across all nations.

Heckscher Ohlin’s theory of international trade in India

Indian emergent markets have grown recently. Trade between major industrialised nations like the United States and other European nations is largely to blame for this. Traditional village farming, modern agriculture, a wide range of contemporary businesses, and a significant quantity of services are all part of India’s varied economy. America and India currently have close cultural, strategic, military, and economic ties. The Heckscher-Ohlin theorem is one hypothesis that analyses the trade between two nations.

The 1990s saw the country start to grow very quickly as markets opened up to foreign competition and investment. India is growing economically and has abundant natural and human resources. India’s economic growth rate was accelerated in the 2000s by economic reforms and stronger economic policy. India’s economy is primarily a domestic market, with 20% of its GDP coming from exports. China, the United States, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, Japan, and the European Union are India’s top trading partners. India’s economy is primarily a domestic market, with 20% of its GDP coming from exports. China, the United States, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, Japan, and the European Union are India’s top trading partners.

The capital/labour ratio is the portion of capital to labour employed in a production that is described in the Heckscher-Ohlin model. Thus, the capital/labour ratios of various industries producing various items will vary. Each nation produces two items in the model, hence it must be assumed which industry has a higher capital-to-labour ratio. For instance, if a nation can produce both steel and clothing, and the production of steel requires more capital per worker than the manufacturing of clothing does, then we would say that the production of steel is more capital-intensive than the production of clothing.

Comparison between India and the United States with regards to the application of the Heckscher Ohlin theory

As India and the United States are two different economies, with the former being developing and the latter exceeding the developed one, a comparison between the two can help the reader distinguish between the theory’s application in economies belonging to different spectrums.

When compared to its workforce, the US possesses a large amount of physical capital. Developing nations have a sizable labour force despite having little physical wealth. Then, to determine the relative factor abundance between nations, we would use the capital-to-labour ratio. For instance, the United States has a higher ratio of total capital to labour than India. Accordingly, we may claim that the United States has more capital than India. India would be more labour-abundant than the United States because of its higher ratio of total labour to capital. The model presupposes that the only distinctions between the two nations are their varying relative endowments of production components.

Based on the characteristics of the countries, the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem predicts the pattern of commerce between them. A country with an abundance of capital is said to export goods that require a lot of capital, whereas a country with an abundance of labour will export goods that require a lot of work. The reason for this is that a country with an abundance of capital generates goods that require significantly more capital during manufacture. As a result, if the two countries stopped trading, the cost of goods in the country with ample capital would decrease due to the increased availability of goods.

This will be contrasted with the cost of identical goods in the other nation. The cost of labour-intensive goods will be the same everywhere there is an abundance of workers. Businesses will relocate their products to markets with higher prices once commerce between the two nations is open. Because the capital-intensive goods will temporarily cost more in the other country, the capital-abundant nation will export them. The labour-intensive goods will be exported from the country with an abundance of workers since the price will temporarily be higher in the other country.

Challenges surrounding the Heckscher Ohlin theory of international trade

The Heckscher-Ohlin theory is frequently at odds with the actual patterns of international trade, despite its plausibility. Wassily Leontief, a Russian-born American economist, carried out one of the earliest studies on the Heckscher-Ohlin hypothesis. Leontief noted that the United States had a respectable amount of capital. Therefore, the reasoning goes, the United States should export commodities that need a lot of capital and import goods that require a lot of labour. He discovered that the contrary was true: American exports typically require more labour than the kinds of goods that the country imports. The Leontief Paradox refers to his results since they were the exact reverse of what the theory predicted.

The Heckscher-Ohlin theory has undoubtedly been shown to be more accurate, precise, scientific, and analytically superior than the prior approaches to the theory of international trade, but it still has several flaws that have led to criticism from numerous writers.

- Although Ohlin’s theory was acknowledged by Haberler to be less abstract, a general equilibrium idea was never developed. It still mostly falls under the partial equilibrium analysis. This theory ignores a number of additional effects, including transport costs, economies of scale, external economies, etc., which also have an impact on the cost of production, in favour of attempting to explain the pattern of trade simply in terms of factor proportions and factor intensities. When multiple factors are simultaneously affecting costs, according to Ellsworth, “it becomes a matter of adding up the influence of all cost-reducing and rising forces to arrive at a net outcome.”

- This theory is built on a set of very oversimplified premises, including perfect competition, resource utilisation at 100%, a production function that is identical, constant returns to scale, the absence of transit costs, and the lack of product differentiation. This collection of presumptions renders the entire model wildly unrealistic.

- Given production functions, incomes, and expenses, the Heckscher-Ohlin model makes the assumption that fixed amounts of production elements exist. This indicates that the theory examines the course of global trade in a fixed environment. Simply put, the results reached from such a study do not apply to a dynamic economic system.

- According to this idea, factors are identical on a qualitative level and may be precisely measured in order to determine factor endowment ratios. However, there are variations in qualitative factors in the real world. Furthermore, each element comes in more than one variation. This poses significant challenges for both determining the trade pattern and measuring and comparing expenses.

- The hypothesis ignores the part that product differentiation plays in global trade. Due to product differentiation, international trade may still occur even though the manufacturing agents are the same in two nations. For instance, American machines are sold out in Japan, whereas Japanese machines are sold out in the United States. According to Wijanholds, factor prices do not impact costs in this situation. Instead, factor prices are determined by commodity prices. According to the HO hypothesis, the export specialisation of various nations is determined by the relative factor proportions (or factor endowments). Labour- and capital-intensive items are exported by countries with ample capital, but the former also export capital-intensive goods. It suggests that trade between nations or regions with comparable relative factor proportions will not occur. However, this is untrue.

- Prices of variables like raw materials, labour, etc., are ultimately dependent on the demand and prices of finished items because the desire for them is the derived demand. Prices of goods are decided by their utility to the buyers (the force of demand). Thus, according to Wijanholds, “prices are the only facts we can accept. Everything else should follow from that. He believes that the Heckscher-Ohlin theory and the Ricardian theory are both flawed because they overlooked the impact of product differentiation on global commerce and linked cost to factor prices”.

Conclusion

Even though the H-O model has undergone several tests over the years and has produced a wide range of outcomes, there is still much we may learn about the theory. Numerous economists have attempted to refute the model, yet the theory is still relevant in economics. Since there is no method for calculating a country’s capital, as many studies have noted, calculating the factor abundance ratio for a country is still exceedingly challenging. Before measurement of labour and capital levels within a particular good is especially challenging. The fundamental presumptions of Heckscher-Ohlin are contested by some. They contend that the model is oversimplified because it makes the assumption that there are no technological distinctions between nations, even though we all know that there are. The model is still helpful in international economics, despite the many criticisms.

Modifications in H-O Model by relaxing assumptions with reference to the assumption of returns to scale, market perfection, Empirical verification and Paradoxes

The classical comparative costs theory developed by Adam Smith, Ricardo and Mill maintained that comparative cost advantage of the trading countries was based on the differences in the productivity of labour (single factor) but they failed to provide a satisfactory explanation for such differences. It is of course true that the relative cost differences or relative differences in commodity prices between two countries are an evidence of their comparative advantage. But what is the fundamental cause of the commodity price differences remained unanswered in the classical theory.

The theory for analysing the pattern of international trade, developed by Swedish economists Eli Heckscher (1919) and Bertil Ohlin (1933) attempted to deal with this vital question. This theory did not supplant the traditional comparative costs theory but supported it by providing explanation for the relative commodity price differences between the countries and their respective comparative advantages. According to them, the differences in commodity prices arise because of the differences in factor endowments (factor supplies) in these countries.

Introduction to Heckscher-Ohlin Theory:

The structure of the modern theory of international trade rests fundamentally upon the theory developed by Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin. This theory has almost completely replaced the classical and neo-classical theories related to international trade. But it does not mean that there is some real conflict between the Hecksher-Ohlin approach and the comparative costs approach or that the former, in any way, invalidates the latter.

In fact, the Heckscher-Ohlin approach supplements the traditional approach in a powerful manner. It goes behind the comparative costs doctrine to investigate the basic cause of the relative differences in costs. Heckscher and Ohlin have traced the cause of cost differences to relative factor endowments and relative factor intensities. That is why this theory is also known as Factor- Proportions-Factor-Intensity Theory. According to this theory, countries which are rich in labour will export labour-intensive goods and those rich in capital will export capital-intensive goods.

Assumptions of the Heckscher-Ohlin Theory:

The H.O. theory is based upon the following assumptions:

(i) This theory considers a two-country, two- commodity and two factor (labour and capital) case. It is possible, however, to extend the theory to a multi-factor and multi-commodity case. But such an extension can be done only if the number of factors and number of commodities are equal.

(ii) The factors of production are perfectly mobile within their respective countries but they are immobile between the countries.

(iii) There is a state of perfect competition both in the product and factor markets.

(iv) There is full employment of the factors of production in both the countries.

(v) Production functions pertaining to both the commodities are linearly homogenous. It implies that the production is governed by constant returns to scale.

(vi) The techniques of production in both the countries remain unchanged. In such a situation, the input-output co-efficient in production functions will remain unchanged.

(vii) The consumer’s taste pattern and therefore the demand functions for different goods are identical in both the countries.

(viii) The factors endowments, in absolute terms, remain constant in both the countries but the relative endowments of the two factors are disproportionate in the two countries. Suppose country A has an abundance of capital while B has an abundance of labour. In qualitative terms, however, the factors are homogenous in the two countries.

(ix) The production functions are such that the two commodities show different factor intensities—one commodity is capital-intensive and the other is labour-intensive. Although production functions for different commodities are different, yet the production functions for each commodity are the same in both the countries.

(x) The factor intensities are not reversible.

(xi) The trade between two countries is free and unrestricted.

(xii) There is an absence of transport costs so that product prices are related exclusively to factor costs.

(xiii) There is incomplete specialisation in the trading countries.

The whole basis of differences in comparative costs, according to H-O theory, rests upon two crucial elements—factor endowments and factor intensities.

Factor Endowments:

It is an incontrovertible fact that regions or countries differ from one another in respect of endowments or availability of factors. In country A, there may be an abundance of capital and labour may be scarce. On the opposite, there may be an abundance of labour in country B, while capital may be scarce.

The terms ‘relative factor abundance,’ in H-O model can be defined in terms of two criteria:

(i) The physical criterion of relative factor abundance, and

(ii) The price criterion of relative factor abundance.

(i) Physical Criterion:

According to this criterion, a country is said to be relatively capital abundant, if and only if, it is endowed with a higher proportion of capital to labour than the other country.

The country A can be called as relatively capital abundant, if the following condition is satisfied:

where K and L refer to capital and labour respectively. Bars over K and L signify the fixed factor quantities in each country. The subscripts A and B refer to countries A and B.

Similarly the relative scarcity of labour, in physical terms, in country A can be expressed as:

For country B, relative labour-abundance can be indicated by:

And capital-scarcity in this country can be denoted by:

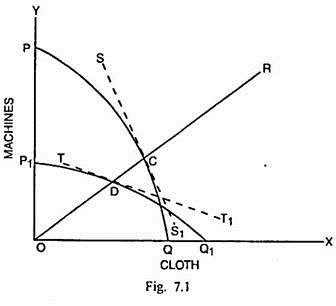

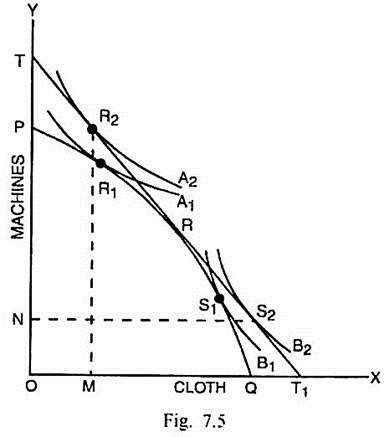

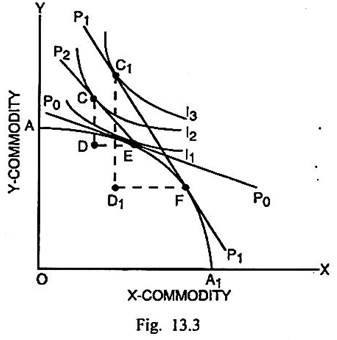

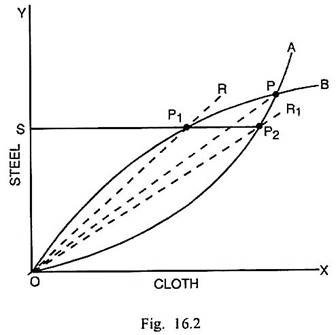

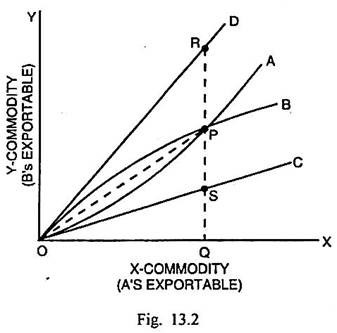

Given the above conditions, H-O theory lays down that country A will produce capital-intensive commodity (say machines) and country B will have a bias in producing labour-intensive commodity (say, cloth). If both the countries produce machines and cloth in the same proportion and production occurs along OR in Fig. 7.1, the country A would be producing at C and country B at D. The points C and D lie on the respective production possibility curves PQ and P1Q1 of these two countries.

Since at point C, the slope of country A’s production possibility curve is more steep than the slope of the production possibility curve of country B at D, this will imply that MC of producing cloth in country A is higher than the MC of producing cloth in country B. So if the production takes place at points C and D, machines can be produced more cheaply in country A and cloth can be produced more cheaply in country B.

Since country A is capital-abundant and the production of machines is capital-intensive, country A will tend to extend the production of machines. Country B, at the same time being labour-abundant, will tend to extend the production of cloth, which is relatively labour- intensive.

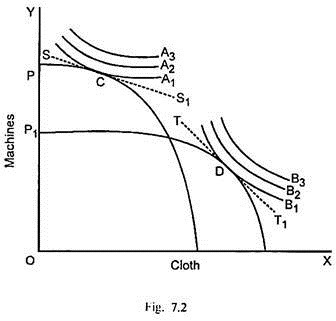

The Heckscher-Ohlin theorem can, however, be valid on the basis of this physical criterion and give the above conclusion only if the consumption pattern in both the countries is identical and the income elasticity of demand for each commodity equals unity. If the demand conditions are different in two countries, the conclusion that capital-abundant countries will export capital-intensive commodity and vice-versa cannot be sustained. This can be shown through Fig. 7.2.

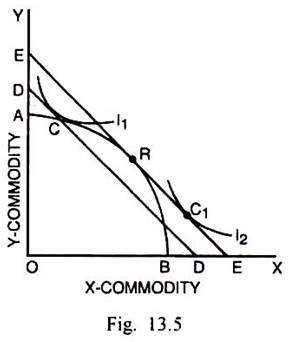

Even in Fig. 7.2, the opportunity cost curves PQ and P1Q1 indicate that country A is capital-abundant and country B is labour-abundant. The pattern of demand is different in the two countries. The community indifference curves A1, A2 and A3 indicate demand pattern in country A and the indifference curves B1, B2 and B3 indicate the demand pattern in country B. The iso-revenue curve SS1 related to country A is less steep than the iso- revenue curve TT1 for country B, therefore-

Now demand conditions indicate that machines are costly in country A while cloth is costly in country B. Therefore, country A may decide to export cloth and country B may export machines. So the pattern of demand may off-set the Heckscher-Ohlin generalisation that capital-abundant country will export capital-intensive commodity and vice-versa.

(ii) Price Criterion:

The alternative criterion for defining relative factor-abundance is the price criterion. The criterion lays down that a country having capital relatively cheap and labour relatively costly is capital-abundant and vice-versa, irrespective of the physical quantities of capital and labour that they have.

Country A can be called as relatively capital-abundant if (PKA/PLA) < (PKB/PLB). Here P denotes prices. K and L signify capital and labour respectively. A and B indicate countries A and B respectively. Similarly country A can be regarded as labour- abundant and capital-scarce, if (PLA/PKA) < (PLB/PKB).

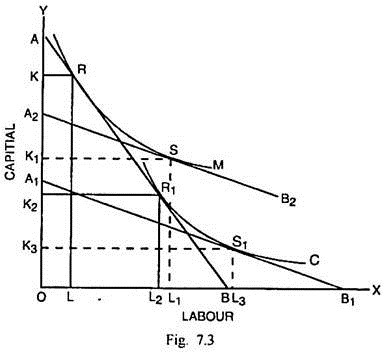

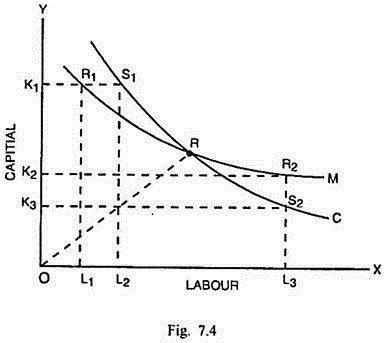

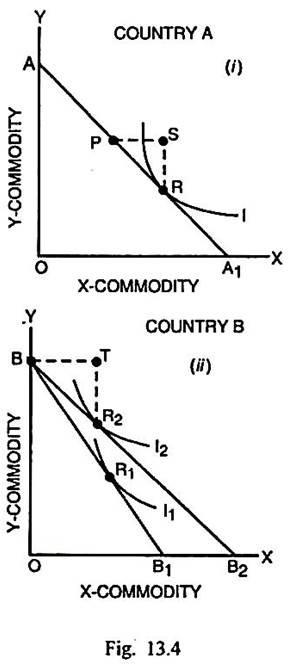

Now suppose country A is capital-abundant and labour-scarce, the interest rates will be relatively low and wage rates will be relatively higher when compared with interest rates and wage rates in country B. Therefore, country A will decide to produce and export capital-intensive commodity (say, machine) and import labour-intensive commodity (say, cloth). Now this generalization can be proved through Fig. 7.3.

AB is the factor-price line for country A and A1B1 is the factor price line for country B. As the slope of AB is greater than that of A1B1, capital is relatively cheap in country A and labour is relatively cheap in country B. It signifies that (PKA/PLA) < (PKB/PLB).

Now the factor price line AB is tangent to the isoquant M of the capital-intensive commodity machine at R. It means country A can produce certain number of units of machine, say 100 machines, by employing OK units of capital and OL units of labour. OL amount of labour is equal to AK amount of capital. In other words, the cost of producing 100 machines in country A in terms of capital is OA.

The factor price line A2B2 of country B is parallel to A1B1. It is tangent to the isoquant M at S. It signifies that country B can produce 100 machines by employing OK1 units of capital and OL1 units of labour. It means A2K1 units of capital are equal to OL1 units of labour and the total cost of producing 100 machines in country B is OA2 in terms of capital. From this, the conclusion can be derived that the production of machine is more capital-intensive in country A than in country B.

Similarly in the production of one unit of cloth (say, 1000 metres) in country A, OL2 units of labour and OK2 units of capital are employed at R1, the point of tangency between country A’s factor price line AB and the isoquant for cloth C representing 1000 meters of cloth. Given this factor combination, OK2 units of capital are equal to BL2 units of labour and the cost of producing 1000 metres of cloth in country A in terms of labour is OB.

In country B, given the factor price line A1B1, the point of tangency between A1B1 and isoquant C is S1. Country B employs OK3 units of capital and OL3 units of labour for producing 1000 metres of cloth. Now the quantity of capital OK3 equals B1L3 units of labour.

The cost of producing 1000 metres of cloth in labour terms is OB1 in country B. This shows that labour-abundant country B makes more use of labour in producing 1000 metres of cloth than country A. B will specialise in the production and export of cloth while country A will export more capital-intensive commodity machine.