1. The Concept of Development and Underdevelopment

a. Change, Progress and Development in Sociology

Introduction:

It has been understood that social change as a term shall signify such changes as affect the nature and structure of social groups and institutions and the social relations between the individual, the group and the institutions in a society.

‘Development’, ‘evolution’ and ‘progress’ are the different modes of change and whenever we speak of social change the importance of each of these modes has to be assessed, for the changes brought about by each of these processes will have distinct impressions upon the functioning’s of social phenomena.

The term ‘development’, as has been discussed earlier, means formal and structural changes in an organism. Even though society is not an entity like the living organism, the term as applied to such organism can have its valid application in social matters. Just as life grows from the simple to the complex form, society develops in the sense that its ‘energy’ accumulates collectively, such energy is ‘organized’ for functioning in a definite direction, and ‘harmony’ is achieved between the different social organs for the purpose of effecting an overall development.

‘Social evolution’ as a term has its complexities and, as has been noticed earlier, evolution in an organism means branching out from a single amoeba into different genera and species and then from the species into various forms that are caused by the process of differentiation.

In the case of a society, as Gisbert puts it in his Fundamentals of Sociology, evolutionary change means a ‘branching off of a line in various directions, which again ramify indefinitely’. A condition of simplicity changes into situations of complexity and social evolution witnesses the progressive development of social ways and customs, norms and beliefs, and associations and institutions. ‘Social progress’ does not mean mere development or evolution, for in either of these terms we have witnessed the change from the simple to the complex.

Though different writers have doubted whether or not changes in society can be regarded as progress and, when the concept of social progress is upheld, what factors determine such progress, the term ‘progress’ has been applied to social change in a few cases. Social progress definitely connotes a valuation and such valuation is made according to certain principles.

If the principle according to which, the valuation is to be made can be objectively ascertained, measuring ‘progress’ does not become a difficult affair; but such principle cannot always remain free from subjective value-judgments. When a subjective analysis confuses ‘progress’ with ‘happiness’ or material comforts, the conclusions tend to remain on the wrong side of value-free judgments and the sociologist must always guard against such pitfalls in reasoning.

Different Theories of Social Evolution:

Evolution, as understood in a living organism, necessarily stands for a process in which simple matter develops into the complex, but such development is always caused by innate qualities of such organism and not by any extraneous factor.

Darwin’s Origin of Species may have crystallized ideas about the phenomenon of development in living organisms, but the concept of it was grasped in some inadequate form or the other by some thinkers even before that. Particularly when it concerns social evolution, the thought has been current for the past century or two; but upon the nature of such evolution there has been difference of outlook between different students of social science.

Herbert Spencer maintains that social evolution is only a part of the general process of evolutionary development in all living matter in the world. Society evolves from the simple form into the complex one as it fulfills the functions of integration and differentiation in its various organs and consequently, out of the same unit of society, different social systems come into existence. According to Spencer, there are three stages in the evolution of society; the first stage is known as ‘integration’, the second as ‘differentiation’ and the final one as ‘determination’.

In the initial stages of social development, the different units of society have to be integrated and a ‘system’ has to be built up. For example, if the family is taken as a basic social unit, the first stage in social evolution was the bringing together of these families and their integration into a larger unit known as ‘society’.

In the second stage of development institutions like division of labour grew up and this process involved itself with differentiation in the sense that different classes, castes and tribes appeared. In the ultimate stage, however, the different segments of society came together and set up a new social structure based on harmony. This was the evolutionary stage of ‘determination’, for in this stage an order was established for the processes of integration and differentiation, so that harmony could be achieved.

Franz Oppenheimer has asserted in his work, ‘The State, that the State evolved in the process of applying certain principles for the satisfaction of man’s creature and basis needs. According to him, there are two ways in which man can supply his basic needs. One of them is work, which is an economic activity, and the other is robbery, that is, exploitation as a political activity; and the State arose when the political means were organized.

Early huntsmen had no state in the sense that they had not exploitative political organization. The State came into being with the Vikings and the herdsmen who learned to exploit, to divide society into classes, to hold slaves and establish the concept of the privileged class and the unprivileged people.

Oppenheimer’s analysis of the development of the State is unsatisfactory; maintaining that the State only robs and exploits is a oversimplication of its functions, since the State performs other functions too, like maintaining law and order and punishing those that violate the law. Besides that, conditions as obtained in a State might have existed even before the State as it is known came into existence; and in effect it becomes difficult to go into the question of the beginnings or the origin of a State as a social organization.

McIver and Page have stressed the importance of the process of differentiation in matters of social evolution. They hold that social evolution stands for an internal change within the social system itself and as a result of such change, functional differences can be brought about within the system. According to them, primitive societies did not have many distinctions observed on the basis of different functions and, besides the differences between tribes, clans, age groups and sex groups, not much of differentiation was noted.

Division of labour in these communities was an undeveloped practice, and associations and organizations did not exist in these societies. The community as such existed on the basis of a simple solidarity and McIver and Page observe that the ‘undifferentiated character’ of the primitive society saw in it ‘the prevalence of a simple form of communism.

Thus, the community devised a system of sharing the hunter’s spoils and, even with regard to matters like sex that are treated as personal and intimate by us, customs and practices prevalent in those days allowed a kind of sharing by the community. If there was any differentiation in such society, it was based on natural distinctions of sex and age, and the multitudinous aspects of differentiation as exist in modern complex society were at best latent, if not totally absent.

According to McIver and Page, associations and organizations in a modern complex society are so many that they immediately strike a contrast with the simple, institution- based primitive society. Historically speaking, diffusion of ideas from the beginnings of the earliest civilizations in Mesopotamia, Persia, India and China perhaps caused the evolutionary development of human thoughts and, therefore, of human society.

But the generic lines of evolutionary development will be best understood if attention is focused upon the following features of such development:

(a) Society has evolved from simple communal customs into various differentiated associations. Codes apply to these associations and each association is developed by an institution comprising of specialized procedure and practice. Thus, political, economic, religious and cultural usages in a community collectively develop into community practices; and from that stage, different forms of procedure evolve as differentiated communal institutions. Finally, these institutionalized procedures become embodied in differentiated associations like the State, the economic organization, the school, the cultural association and the like.

(b) The Associational stage in society is so radically different from the levels that obtained in the primitive society that it has introduced an entirely different form of social relationships. There are voluntary and involuntary associations, and each great association structurally and functionally differs from the other.

For example, in the second stage of development as shown above, only one set of political institution exists for the whole society, or one set of religious institution is appreciated. But in the third and the associational stage, several political organizations and diverse ideas regarding the State are entertained, just as the religious organization diversifies into various forms of religious associations. The Church, for instance, began as a religious institution in the second stage of development of society; but in the final stage it has advanced into the form of different religious associations.

(c) When social events are studied historically, they present the earlier types of social units and the later types of the same. The differentiation between these types helps us to classify and characterize the diverse social systems as they evolved historically as also to understand the causes in the evolutionary processes that brought about definite results.

Hence, there is a historical pattern in social evolution and, if effects are noticed in the evolutionary process, there must be causes that explain such differentiation. This particular view of McIver and Page is not totally different from the observations made by M. Ginsberg in his Studies in Sociology.

Ginsberg says that evolution is a process of change culminating in the production of something new but exhibiting an orderly continuity in ‘transition’. McIver and Page also admit that in the evolutionary process certain factors cause the change which is but an orderly expression of a new form that has culminated from an older one.

However, Ginsberg would not admit that social evolution implies the change from the simple to the complex as McIver would put it. His idea of evolution is that while the process of transition introduces something new, such novelty is but a continuity of some social element that is permanent. Evolution truly speaking means a change that comes from within but, as Ginsberg points out extraneous factors also condition social evolution, and his view is that evolutionary changes in society are best understood when the subjects of society, that is, the individuals are taken into account.

He maintains that ‘the real subjects undergoing development are men of societies who speak and think and are religious’. If this view alone is taken, it would not mean that social evolution stands for substituting the simple organism by the complex one; it would rather mean that evolutions occur in thoughts and ideas and in the interaction of human social relations.

But then human interactions and social relations cannot exist in complete detachment from social customs and institutions. Every social event is the effect of complex action and reaction of human relations just as human social relations are the effect of the complex functioning of the social structure. Ginsberg says that ‘if individuals make society, it is equally true that society makes individuals’.

It follows, therefore, that a mere concentration upon human actions and reactions for the proper gauging of social change will be an inadequate approach; it must be accepted that social change as a concept is an evolution of the individual as well as of the society itself.

Social Change and Progress:

Every event of social change cannot be regarded as progress, for progress must connote the taking of a step forward. If at the root of evolution we have the stages of integration and differentiation, progress would stand for a development in a particular direction which is regarded as a step forward according to definite criteria of value- judgments.

While evolution has no definite direction other than the one which is inherent and irresistible in itself, progress must stand for a march in a forward direction according to some accepted principle that is formulated by a particular principle of judgment.

Ginsberg maintains (Idea of Progress) that progress ‘is a development or evolution in a direction which satisfies rational criteria in value’. In order to measure progress, it is necessary to apply the test of ethical advancement made by society which, of course, is an irrelevant factor so far as evolution is concerned.

Writers like Comte and Spencer would maintain that any evolutionary development of society must necessarily mean that it has progressed. Herbet Spencer particularly insists that social evolution cannot have any meaning other than that of progress. But these views are not accepted now by more modern writers. McIver states in his Society that ‘evolution is a scientific concept and progress an ethical concept’.

Even Hobhouse observes that evolution of any form does not necessarily imply that it is changing into the better form; and, therefore, we cannot conclude that evolution necessarily implies that society is progressing.

According to him, progress can be made only when the individual in society strives for ethical advancement. Social progress, therefore, is not a phenomenon marked by spontaneity; it is the product of conscious efforts made by social individuals.

The concept of progress is based on the vision of an ideal society in which every individual will have the opportunity of developing his innate qualities, in which the very basis of social relations will be principles of liberty and equality, and in which the institutions will aim at comprehending the foundations of collective good. These are, however, matters of value-judgments and the concept of progress cannot be understood without applying the test of values. Evolution, as a term, does not depend upon these values.

Some modern sociologists, however, feel that the science of sociology is not concerned with ethics and, therefore, the term ‘social progress’, which cannot be understood unless it is related to ethical values, will not be the concern of the sociologist and will consequently have no scientific value. They maintain that no scientific observation and rational conclusion shall be based on any ethical value.

If the method followed by the sociologist in the study of society is that of positive science, and if the principles of causation are to be objectively investigated into, it will be an anomaly if facts are correlated to values. However, social facts cannot be regarded as isolated phenomena; every social event has a practical side to it and another concerning values. McIver and Page observe that social facts can also be regarded as ‘value-facts’ since social valuation is much concerned with them.

Therefore, the authors maintain, that science appreciates value-judgments, first, in order to test the accuracy of factual evidence in support of a value-judgment and, secondly, for testing the validity of conclusions regarding the good or the bad in so far as these conclusions are supported by reasoning from statements of facts.

For example, valuations obtainable in any social institution may be studied scientifically in order to test their validity, but the sociologist shall not apply his own personal judgment to such valuations which are ingrained in the social facts themselves. In this way, a value- judgment can be objectively made in upon the term ‘social progress”, but the social scientist must begin his work by looking upon evolution as a value-free fact.

Thus, one may objectively determine the degree of progress made by a particular society only after one has disinterestedly studied the growth of its associations and institutions and the psychological elements in social relations between individuals in it.

An objective study of social progress can be facilitated by considering the factors that hinder and obstruct advancement in material as well as psychological terms. Any rigid attitude towards scientific development of material conditions will have both material and psychological implications.

If science and technology is looked upon with suspicion and if there is a blind adherence to outmoded custom, material development in the society will not be achieved, while social mentality in general will remain unliberated.

But if technology is applied to the processes of developing and utilizing natural resources, material advancement will undoubtedly take place; and at the same time, man will have enough scope of cultivating constructive thoughts about developing his families. His social and moral consciousness grows in degree and he learns to propagate the idea of integrating efforts in the direction of realizing the common good.

Hence, we can conclude that the society in which scientific development is hindered will not progress, while the one which encourages such development will have chances of making progress; and this observation about social progress can remain scientific in so far as it is based on social facts and not merely upon ethical considerations.

However, there are problems connected with the adoption of a scientific attitude towards the study of social change, whether such change speaks of evolutionary development or of mere progress. Social change as a phenomenon is so complex by itself that the analysis of no single factor can lead us to a definite conclusion.

In trying to explain any phenomenon scientifically, any of the following mistakes can be made:

(a) The scientist may think that any one of the many factors relating to such phenomenon is the dominant factor; and

(b) He may assume that social forces can be quantitatively measured.

For example, if it is to be considered why the middle classes in India grew under the British rule; it may be wrong to conclude that this class grew and developed only because it applied itself to the task of promoting the standards of British-oriented professions and occupations; besides that, there might have been other factors too which contributed to the growth of that class.

Similarly, if the social scientist allows himself to conclude from a number of social facts in the same manner in which quantitative conclusions are made following a study of a number of guinea pigs, he will not acquire for himself a proper perspective of the complex pattern of social facts.

The truth is that in the primitive society, the people unified social authority with their techniques and culture, and the basic personality structure of every individual was ascertainable. The simplified study of the primitive individual may then be possible, but modern complex society has introduced so many factors for the interplay of social relations that the scientist’s task does not remain simple.

Technological advancement has in modern times broken up the primitive unity of social authority, technique and culture. Culture has been detached from other biophysical factors and within the same society different cultures and subcultures may coexist. In the modem social system, specialization and the diversity of numerous groups and associations have given to society such multifarious facts that the sociologist cannot afford either to isolate one social factor for study or derive conclusions from a number of social facts.

Thus, he must realize that several factors combine to produce social changes and, as these factors make the combination, they interrelate themselves within the larger environment of society. The study of social change must, according to McIver, take into account the attitudes that depend on a particular cultural background and the objectives to which such attitudes are related, the system of means for fulfilling such objectives, and the physical and biological conditions that prompt the changing objectives and the human nature that follows them.

The scientist must first study the interrelationship of the various factors, analyse the logical order in which they fall, and finally build up an observation upon the manner in which they make up the casual process in which social change is effected.

b. Economic Approach to Development

Meaning of the term ‘Economic Development’

Actually, there are broadly two main approaches to the concept of economic development :

- The Traditional Approach or ‘The Stages of Economic Growth’ Theories of the 1950s and the early 1960s.

- The New Welfare Oriented Approach or ‘The Structural-Internationalist’ Models of the late 1960s and the 1970s.

1. The Traditional Approach :

The thinking of the 1950s and early 1960s focused mainly on the concept of the stages of economic growth. Here the process of development was viewed as a series of successive stages through which all countries had to pass. The propounders of this approach advocated the necessity of the right quantity and mixture of saving, investment and foreign aid to enable the LDCs to proceed along an economic growth path. They based their conclusions on the fact that this economic path historically had been followed by most of the more developed countries. Thus, in this period development had become synonymous with rapid, aggregate economic growth.

This approach defined development strictly in economic terms and it implied :

- A sustained annual increase in the GNP at rates varying from 5 to 7 pcpa or more;

- Such changes in the structure of production and employment that the share of agriculture declines in both, while the share of manufacturing and the tertiary sectors increase.

The policy measures that were suggested in this period were the ones which induced industrialization at the expense of agricultural development. The objectives of poverty elimination, economic inequalities reduction and employment generation were mentioned but only as a passing reference. In most cases it was assumed that the rapid gains in overall growth in the GNP would ‘trickle-down to the masses’ in one form or the other.

2. The New Welfare Oriented Approach:

Jacob Viner was probably the first economist (1950’s) to argue that an economy could not boast of having achieved economic progress if the incidence of poverty in that economy had not diminished. But it was in the early 1970’s that economists began to realize that Jacob Viner’s stance was relevant, as nearly 40 % of the developing world’s population had not benefited at all from the rise in the GNP and from the structural changes that had taken place in their respective economies during the 1950’s and 1960’s.

Hence, in the 1970s it became necessary to redefine the concept of economic development. This modern approach views underdevelopment in terms of :

- international and domestic power relationships;

- institutional and structural economic rigidities; and,

- the proliferation of dual economies and dual societies both within and among the nations of the world.

This approach places emphasis on policies that would lead to the eradication of poverty, provide more diversified employment opportunities, and reduce income inequalities. This approach insists that these and the other egalitarian objectives have to be achieved only within the socio-economic context of the respective growing economy. Thus today, economic development is a process whereby the general economic well-being (especially of the masses) of an economy is affected for the better.

Meier defines economic development very concisely as:

‘Development is the process whereby the real per capita income of a country increases over a long period of time – subject to the stipulation that the number below an absolute poverty line does not increase and that the distribution of income does not become more unequal’.

This definition thus highlights the following aspects of the term economic development :

1. Development is a PROCESS :

Today, development implies the operation of certain socio-economic forces in an interconnected and causal fashion. This interpretation is more meaningful than merely to identify development with a set of conditions or a catalogue of characteristics.

2. Development is a RISE IN THE REAL PER CAPITA INCOME :

Since today the development of a poor country arises from a desire to remove its mass poverty, the primary goal should be a rise in the real PCI rather than simply an increase in the economy’s real national income, uncorrected for changes in the population. Simply increasing the real national income does not guarantee that there would be an improvement in the general living standards of the masses. If the population growth rate surpasses the growth of national output or even runs parallel with it, the result would be a falling or at best a constant PCI and as this would not be beneficial to the masses, it cannot be considered as development.

3. Development can take place only over a LONG PERIOD OF TIME :

This time period is significant from the stand-point of development being a sustained increase in the real income and not simply as a short-period temporary rise, such as occurs during the upswing of the business cycle. The underlying continuous upward trend in the growth of the real PCI over at least two or three decades is a strong indication that the process of development is on the right track.

4. Development must lead to a DECREASE IN SIZE OF THE ABSOLUTELY POOR :

Given the new orientation of the development thought, it is necessary that the quality of life of the masses must improve – in fact improve to the extent of actually showing a fall in the amount of people living below the poverty line. This would automatically require, as suggested in the definition, a reduction in the economic inequalities in the economy. To achieve this goal, it is necessary that the policies implemented should actually divert economic power towards the economically vulnerable groups in the economy. The policies should aim at raising the real PCI, causing a diminution in economic inequality (ie., an alleviation if not an eradication of poverty), ensuring a minimum level of consumption, guaranteeing a certain socially relevant composition of the national income, reducing unemployment to a tolerable low level and removing regional development disparities.

The framework of development as given by Charles P. Kindleberger and Bruce Herrick reiterates the improvement-of-the-masses emphasis of Meier’s definition. Kindleberger and Herrick maintain that economic development is generally taken to include :

- Improvement in material welfare, especially for persons with the lowest incomes, the eradication of mass poverty along with its correlates of illiteracy, disease, and early death;

- Changes in the composition of inputs and outputs that generally include shifts in the underlying structure of production away from agricultural and towards industrial activities;

- Organizing the economy in such a way that productive employment is general among the working age population and that employment is not a privilege of only a minority; and,

- Increasing the degree of participation of the masses in making decisions about the directions, economic and otherwise, in which the economy should move to improve their own welfare.

The Economic Growth V/s Economic Development dEBATE

The stress on the improvement in the quality of life of the masses has made it imperative to distinguish between the growth-oriented approach of the 1950s & 1960s and the modern development-oriented approach of the late 1960s & 1970s – ie., the distinctions between Economic Growth and Economic Development must be highlighted.

1. Definitional differences :

Economic growth is a pure economic process whereby there is an increase in the economy’s GNP due to the increase in the productive capacity of the economy. Economic development, on the other hand, is a multi-dimensional process involving major changes in the social structures, popular attitudes and national institutions, as well as the acceleration of economic growth, the reduction of inequality and the eradication of absolute poverty.

2. Differences in the objectives :

Economic growth aims at:

- Increasing the size of the GNP, without actually considering the social relevance of the composition of the national income.

- Removing all the obstacles that could come in the way of increasing the economy’s productive capacity, eg., removing the market imperfections that exist in the economy.

- Supplying the ‘missing components’ like capital, foreign exchange, technology, skills and management, which are needed for improving the economy’s productive capacity.

- Hoping that the benefits of the increased capacity of the economy would some how reach the masses.

Economic development, on the other hand, aims at :

- Increasing the availability and widening the distribution of basic life-sustaining goods such as food, shelter, health and protection.

- Raising the level of living including, in addition to higher incomes, the provision of more jobs, better education and greater attention to cultural and humanistic values, all of which serve not only to enhance material well-being but also to generate greater individual and national self-esteem.

- Expanding the range of economic and social choice to individuals and nations by freeing them from servitude and dependence, not only in relation to other people and nations, but also from the forces of ignorance and human misery.

Thus, we see that the goals of economic growth are rather narrow in scope, while those of economic development are more broad-based in nature and in scope.

3. Differences in the overall approach :

a. Quantitative versus Qualitative Approaches :

According to Kindleberger, economic growth means more output, while economic development implies not only more output but also changes in the technical and institutional arrangements by which it is produced and distributed. Growth involves more output derived from greater amounts of inputs and with greater efficiency; but, development implies changes in the composition of the output and in the allocation of the inputs to the different sectors. Thus, growth is related to a quantitative sustained increase in the PCI accompanied by the expansion in its labour force, consumption, capital and volume of trade, while economic development is related to qualitative changes in economic wants, goods, incentives and institutions.

b. Revolutionary Speed versus Evolutionary Speed Approaches :

Economic growth implies a certain degree of rapidity in the change process. Changes are introduced at a brisk rate and without a sufficient preparation of the socio-eco-politico foundations of the economy. Projects are literally imposed on the economy to create a global impression of progress. The masses are either not taken into confidence or are not considered vis-à-vis the new projects. The rapid changes caused by the ‘Revolutionary Approach’ of economic growth ensure the failure of the system within a short time.

Our academic experts are ready and waiting to assist with any writing project you may have. From simple essay plans, through to full dissertations, you can guarantee we have a service perfectly matched to your needs.

Economic Development, on the other hand, adopts a more ‘Evolutionary Approach’– ie., it first ensures that the socio-eco-politico foundations are readied for the change. Hence, when the change actually takes place, it is readily and popularly accepted and supported. Thus, development involves creating a sense of awareness and a feeling of participation among the masses in the economy. This makes the development process painstakingly slow, long and drawn-out – but it is this gradualness in approach that actually strengthens the economy in the long run.

c. Only Immediate Gains versus Also Futuristic Gains Approaches :

The gains that accrue from economic development are far more sustaining than those made from growth, simply because of the differences in the way the future of the to-be-introduced projects are anticipated, analyzed and appreciated. Economic growth means increasing the economic activities, irrespective of whether the economy can continue supporting the newly introduced economic activity in the long run or not. For instance, along the lines of economic growth, an LDC would increase its current steel producing capacity, but it would not be able to keep up this new capacity for more than a few years. Hence, within a few years, the increased capacity would lay wasting leading to a wastage of scarce resources. Economic development, on the other hand, would consider the future sustaining capacity of the economy before actually increasing the steel capacity. If and only if the economy can continue supporting this higher rate in the future, the capacity would actually increase. Thus, economic development guarantees that the scarce resources are currently used fruitfully and appropriately.

d. Only Economic versus Also Environmental concern Approaches :

Economic growth, due to its rapid approach, more often than not, causes harm to the environment – natural and/or social. Projects are undertaken without considering the cascading effects that could follow in the form of natural environment degradation, pollution, overcrowding, increase in crime rate, bottlenecks in infrastructural facilities, etc. For instance, an economy, for growth’s sake, could undertake an irrigational project without either making a thorough study of or without caring about its ramifications on the natural and social environment.

Economic development, on the other hand, insists on the conservation and the protection of the natural and social environment. If a certain project could cause any sort of significant damage to the environment, that project would be either abandoned or altered. If the above mentioned irrigational project was approached from the development point of view, its site would be either changed, or its dimensions altered to prevent natural environmental harm; and if there is any sort of social environmental damage, like displacement of the inhabitants, then, rehabilitation projects would be undertaken, in consultation with the affected people.

e. The Trickle-Down versus The Direct-Attack Approaches :

Economic growth’s, primary goal is to increase the productive capacity of the economy massively, irrespective of whether or not the poorer sections would benefit from this higher capacity. In fact, growth works on the assumption that the benefits that accrue from the increase in capacity would some how or the other trickle-down to the masses. Thus, growth makes no deliberate attempt ensure that the benefits do reach the poorer sections of the economy. The objectives of poverty eradication, economic inequalities reduction and employment generation are mentioned but only as a passing reference, as secondary gains that may or may not occur. Growth has a sort of an in-built tendency to bypass those very people in the economy who deserve to be supported the most by it.

Economic development, on the other hand, by directly attacking economic misery, ensures that the benefits of the increase in the productive capacity actually reach the masses. The policies aim at diverting economic power towards the economically weaker sections of the economy. The policies directly aim at raising the real PCI, causing a diminution in economic inequality, ensuring a minimum level of consumption, guaranteeing a certain socially relevant composition of the national income, reducing unemployment to a tolerable low level and removing regional development disparities.

4. Interrelationship between Economic Growth & Economic Development :

Although economic growth and economic development are indeed very different in their approaches, there exists an inter-relationship between them. It is difficult to conceive of development without growth. In low income countries, for instance, a substantial increase in the GNP is needed before they can hope to overcome their problems of poverty, unemployment and occupational distribution. However, it is possible to have growth without development, as growth is not concerned with the social aspects of an economy. In short, since development is a broader concept it encompasses growth and therefore can be said to be directly related to growth. Thus, development is growth with a human face.

c. Modernisation Approach to Development

By the end of the Second World War many of the countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America had failed to develop and remained poor, despite exposure to capitalism. There was concern amongst the leaders of the western developed countries, especially the United States, that communism might spread into many of these countries, potentially harming American business interests abroad and diminishing U.S. Power.

In this context, in the late 1940s, modernisation theory was developed, which aimed to provide a specifically non-communist solution to poverty in the developing world – Its aim was to spread a specifically industrialised, capitalist model of development through the promotion of Western, democratic values.

There are two main aspects of modernisation theory – (1) its explanation of why poor countries are underdeveloped, and (2) its proposed solution to underdevelopment.

Modernisation theory explained the underdevelopment of countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America primarily in terms of cultural ‘barriers’ to development’, basically arguing that developing countries were underdeveloped because their traditional values held them back; other modernisation theorists focused more on economic barriers to development.

In order to develop, less developed countries basically needed to adopt a similar path to development to the West. They needed to adopt Western cultural values and industrialise in order to promote economic growth. In order to do this they would need help from Western governments and companies, in the form of aid and investment.

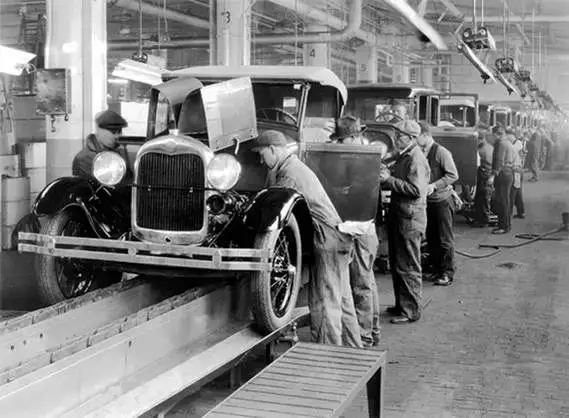

Modernisation theory favoured a capitalist- industrial model of development – they believed that capitalism (the free market) encouraged efficient production through industrialisation, the process of moving towards factory based production.

Industrial –refers to production taking place in factories rather than in the home or small workshops. This is large scale production. (Think car plants and conveyer belts).

Capitalism – a system where private money is invested in industry in order to make a profit and goods are produced are for sale in the market place rather than for private consumption.

There are alternative systems of production to Capitalism – subsistence systems are where local communities produce what they need and goods produced for sale are kept to a minimum; and Communism, where a central authority decides what should be produced rather than consumer demand and desire for profit. (Need drives production in Communism, individual wants or desires (‘demand’) in Capitalism)

Modernisation Theory: What Prevents Development?

According to Modernisation Theorists, obstacles to development are internal to poorer countries. In other words, undeveloped countries are undeveloped because they have the wrong cultural and social systems and the wrong values and practices that prevent development from taking place.

Talcott Parsons (1964) was especially critical of the traditional values of underdeveloped countries – he believed that they were too attached to traditional customs, rituals, practices and institutions, which Parsons argued were the ‘enemy of progress’. He was especially critical of the extended kinship and tribal systems found in many traditional societies, which he believed hindered the geographical and social mobility that were essential if a country were to develop (as outlined in his Functional Fit theory).

Parsons argued that traditional values in Africa, Asia and Latin America acted as barriers to development which included –

- Particularism – Where people are allocated into roles based on their affective or familial relationship to those already in positions power. For example, where a politician or head of a company gives their brother or someone from their village or ethnic group a job simply because they are close to them, rather than employing someone based on their individual talent.

- Collectivism – This is where the individual is expected to put the group (the family or the village) before self-interest – this might mean that children are expected to leave school at a younger age in order to care for elderly parents or grandparents rather than staying in school and furthering their education.

- Patriarchy – Patriarchal structures are much more entrenched in less developed countries, and so women are much less likely to gain positions of political or economic power, and remain in traditional, housewife roles. This means that half of the population is blocked from contributing to the political and economic development of the country.

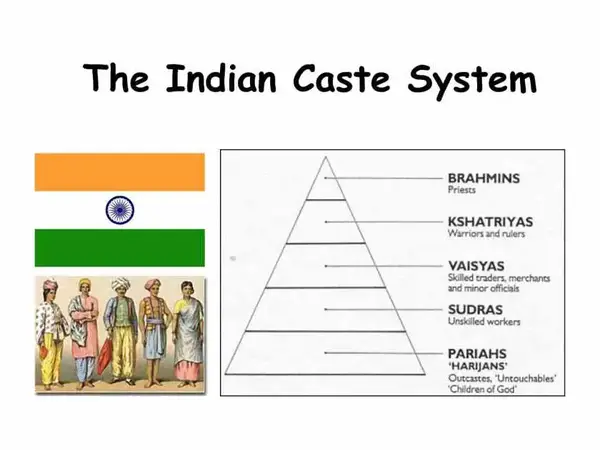

- Ascribed Status and Fatalism – Ascribed status is where your position in society is ascribed (or determined) at birth based on your caste, ethnic group or gender. Examples include the cast system in India, many slave systems, and this is also an aspect of extreme patriarchal societies. This can result in Fatalism – the feeling that there is nothing you can do to change your situation.

In contrast, Parsons believed that Western cultural values which promoted competition and economic growth: such values included the following:

- Individualism – The opposite of collectivism This is where individuals put themselves first rather than the family or the village/ clan. This frees individuals up to leave families/ villages and use their talents to better themselves ( get an education/ set up businesses)

- Universalism – This involves applying the same standards to everyone, and judging everyone according to the same standards This is the opposite of particularism, where people are judged differently based on their relationship to the person doing the judging.

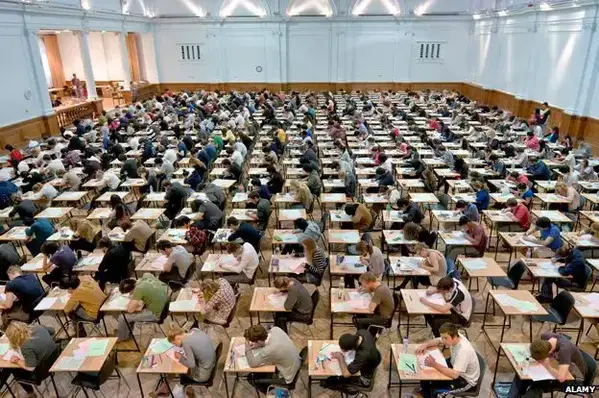

- Achieved Status and Meritocracy – Achieved status is where you achieve your success based on your own individual efforts. This is profoundly related to the ideal of meritocracy. If we live in a truly meritocratic society, then this means then the most talented and hardworking should rise to the top-jobs, and these should be the best people to ‘run the country’ and drive economic and social development.

Parsons believed that people in undeveloped countries needed to develop an ‘entrepreneurial spirit’ if economic growth was to be achieved, and this could only happen if less developed countries became more receptive to Western values, which promoted economic growth.

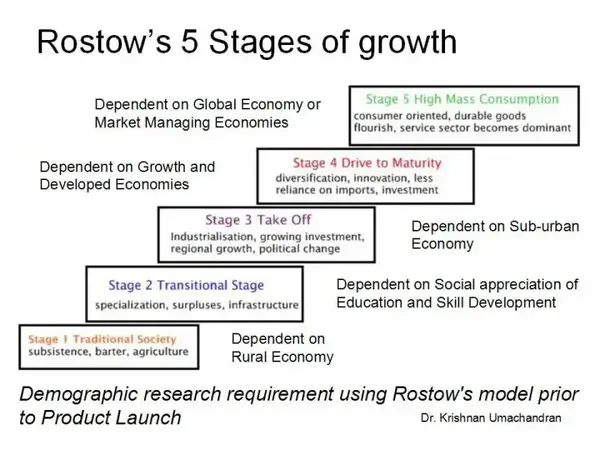

Rostow’s five stage model of development

Modernisation Theorists believed traditional societies needed Western assistance to develop. There were numerous debates about the most effective ways to help countries develop, but there was general consensus on the view that aid was a good thing and if Developing countries were injected with money and western expertise it would help to erode ‘backward’ cultural barriers and kick starts their economies.

The most well-known version of modernization theory is Walt Rostow’s 5 stages of economic growth. Rostow (1971) suggested that following initial investment, countries would then set off on an evolutionary process in which they would progress up 5 stages of a development ladder. This process should take 60 years. The idea is that with help from West, developing countries could develop a lot faster than we did.

Stage 1: Traditional Society

Traditional societies whose economies are dominated by subsistence farming. Such societies have little wealth to invest and have limited access to modern industry and technology. Rostow argued that at this stage there are cultural barriers to development (see sheet 6)

Stage 2: The preconditions for take off

The stage in which western aid packages brings western values, practises and expertise into the society. This can take the form of:

- Science and technology – to improve agriculture

- Infrastructure – improving roads and cities communications

- Industry – western companies establishing factories

These provide the conditions for investment, attracting more companies into the country.

Stage 3: Take off

The society experiences economic growth as new modern practices become the norm. Profits are reinvested in infrastructure etc. and a new entrepreneurial class emerges and urbanised that is willing to invest further and take risks. The country now moves beyond subsistence economy and starts exporting goods to other countries

This generates more wealth which then trickles down to the population as a whole who are then able to become consumers of new products produced by new industries there and from abroad.

Stage 4: The drive to maturity

More economic growth and investment in education, media and birth control. The population start to realise new opportunities opening up and strive to make the most of their lives.

Stage 5: The age of high mass consumption

This is where economic growth and production are at Western levels, which should have happened after 60 years according to Rostow.

Variations on Rostow’s 5 stage model

Different theorists stress the importance of different types of assistance or interventions that could jolt countries out their traditional ways and bring about change.

- Hoselitz – education is most important as it should speed up the introduction of Western values such as universalism, individualism, competition and achievement measured by examinations. This was seen as a way of breaking the link between family and children.

- Inkeles – media – Important to diffuse ideas non traditional such as family planning and democracy

- Hoselitz – urbanisation. The theory here is that if populations are packed more closely together new ideas are more likely to spread than amongst diffuse rural population

Strengths of Modernisation Theory

Below are some examples of the theory working in practice, sort of!

ONE – Indonesia – partly followed Modernisation theory in the 1960’s by encouraging western companies to invest and by accepting loans from the World Bank. But, their President Suharto (Dictator) also maintained a brutal regime which a CIA report refers to as “one of the worst mass murders of the 20th century,” comparable to those of Hitler, Stalin, and Mao. However, the World Bank praised Suharto’s economic transformation as “a dynamic economic success” and called Indonesia “the model pupil of the global economy,” while Bill Clinton referred to Suharto as “our kind of guy.”

Two further examples of where western expertise has helped solved specific problems in a number of developing countries are the green revolution and the eradication of smallpox, but neither of these lead to ‘the high age of mass consumption’ as Rostow predicted

TWO – The Green Revolution: In the 1960s, Western Biotechnology helped treble food yields in Mexico and India.

THREE – The Eradication of Smallpox… In the early 1950s 50 million cases of smallpox occurred in the world each year, by the early 1970s smallpox had been eradicated because of vaccine donations by the USA and RUSSIA

Criticisms of Modernisation Theory

There are no examples of countries that have followed a Modernisation Theory approach to development. No countries have followed Rostow’s “5 stages of growth” in their entirety. Remember, “Modernisation Theory” is a very old theory which was partly created with the intention of justifying the position of western capitalist countries, many of whom were colonial powers at the time, and discrediting Communism. This is why it is such a weak theory.

Modernization Theory assumes that western civilisation is technically and morally superior to traditional societies. Implies that traditional values in the developing world have little value compared to those of the West. Many developed countries have huge inequalities and the greater the level of inequality the greater the degree of other problems: High crime rates, suicide rates, poor health problems such as cancer and drug abuse.

Dependency Theorists argue that development is not really about helping the developing world at all. It is really about changing societies just enough so they are easier to exploit, making western companies and countries richer, opening them up to exploit cheap natural resources and cheap labour.

Neo-Liberalism is critical of the extent to which Modernisation theory stresses the importance of foreign aid, but corruption (Kleptocracy) often prevents aid from getting to where it is supposed to be going. Much aid is siphoned off by corrupt elites and government officials rather than getting to the projects it was earmarked for. This means that aid creates more inequality and enables elites to maintain power.

Post-Development thinkers argue that the model is flawed for assuming that countries need the help of outside forces. The central role is on experts and money coming in from the outside, parachuted in, and this downgrades the role of local knowledge and initiatives. This approach can be seen as demeaning and dehumanising for local populations. Galeano (1992) argues that minds become colonised with the idea that they are dependent on outside forces. They train you to be paralysed and then sell you crutches. There are alternative models of development that have raised living standards: Such as Communist Cuba and The Theocracies of the Middle East

Industrialisation may do more harm than good for many people – It may cause Social damage – Some development projects such as dams have led to local populations being removed forcibly from their home lands with little or no compensation being paid.

In the clip below, Vandana Shiva presents a useful alternative perspective on the Green Revolution, pointing out that many traditional villages were flooded and destroyed in the process:

Finally, there are ecological limits to growth. Many industrial modernisation projects such as mining and forestry have led to the destruction of environment.

Neo-Modernisation Theory

Despite its failings Modernisation theory has been one of most influential theories in terms of impact on global affairs. The spirit of Modernisation theory resulted in the establishment of the United Nations, The World Bank and the IMF, global financial institutions through which developed countries continue to channel aid money to less developed countries to this day, although there is of course debate over whether aid is an effective means to development.

Furthermore, the ‘spirit of Modernisation theory may actually still be alive today, in the form of Jeffry Sachs. Sachs (2005) is one of the most influential development economists in the world, and he has been termed a ‘neo-modernisation theorist’.

Sachs, like Rostow, sees development as a ladder with its rungs representing progress towards economic and social well-being. Sachs argues that there are a billion people in the world who are too malnourished, diseased or young to lift a foot onto the ladder because they often lack certain types of capital which the west takes for granted – such as good health, education, knowledge and skills, or any kind of savings.

Sachs argues that these billion people are effectively trapped in a cycle of deprivation and require targeted aid injections from the west in order to develop. In the year 2000 Sachs even went as far as calculating how much money would be required to end poverty – it worked out at 0.7% of GNP of the 30 or so most developed countries over the next few decades.

d. Sustainable Development

The definition of the concept of Sustainable Development put forward in the report titled Our Common Future is: “Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. It contains within it two key concepts:

i. The concept of “needs”, in particular the essential needs of the world’s poor, to which overriding priority should be given; and

ii. The idea of limitations imposed by the state of technology and social organisation on the environment’s ability to meet present and future needs”.

In order to understand the meaning of the definition, it is essential to understand the core issues addressed in the above definition. First is the issue of economic growth. The economic growth is not only considered essential for poverty reduction but also for meeting human needs and aspirations for better life.

Second is the issue of limitations of the environment’s ability to meet the needs of the present and future generations. Due to the pressures generated by growing societal needs, societies are using modern technologies for extracting and utilising natural resources, which are limited. If we continue to exploit existing limited natural resources, future generations will not be able to meet their own needs.

Thus, environment’s ability to meet present and future generations’ needs has certain limits. This realisation is clearly reflected in the definition. Thus, the concept of “sustainable development” is based on an integrated view of development and environment; it recommends pursuance of development strategies in order to maximise economic growth from a given ecological milieu on the one hand, and to minimise the risks and hazards to the environment on the other; for being able to meet the needs and aspirations of the present generation without compromising the ability to meet those of the future generations. K.R. Nayar looks at the concept of “sustainable development” as a political instrument and is critical of many aspects of the Commission’s definition.

He argues that, “the concept of sustainable development has emerged from those countries which themselves practice unsustainable resource use”, and further adds that “the politics of ‘sustainable development’ is that at present it is anti-south, anti-poor, and thereby anti- ecological”.

Nayar also comments that, “the need” with reference to sustainable development is affluence rather than basic, or opulence rather than squalor. Because, when basic needs become an integral component of a developmental model, the question of unsustainability does not arise”. He further adds, “The cyclical relationship between poverty and environmental degradation is conceptualised in simplistic terms”.

The assumption is that, as poverty increases, natural environments are degraded and when environments degrade, the prospects for further livelihood decrease, environmental degradation generates more poverty, thus accelerating the cycle. While the basic factors which generate poverty are kept outside this framework, it also does not consider the role of lopsided development which degrades the ‘natural’ capital, and the issue of artificially inflated impact of the poor on an already lower quality of ‘natural capital’ set in motion by factors other than poverty”.

While uncovering the implicit political motive behind the Western concern for curtailment of population growth in the developing countries for sustainable development, Nayar expresses the view that, “sustainable development is visualised as a solution to make available raw materials on a continuous basis so that the production system, the expanding market and the political system are not threatened. The raw materials in the developing countries, therefore, need to be protected and their population growth curtailed so that resources would remain easily available.”

Again, in his opinion, “The Not-in-My-Back-Yard or Nimby syndrome is mainly responsible for ecologically unsustainable development projects including hazardous industries shifting out of these countries to developing countries. When the aim is to suggest patchwork solutions to the unsustainable production system of the north, population growth in the south automatically becomes the target of the debate on sustainable development”.

In short, the above definition of “sustainable development” implies that: (i) we should direct our efforts towards redressing the damage already done to the environment by earlier unsustainable patterns of economic growth and, (ii) we should follow such a pattern of development which avoids further damage to the planet’s ecosystem and ensures meeting of the needs of present as well as future human generations.

The report, Our Common Future also recommends that in order to move on the path of sustainable development, all nations are required to bring about certain policy changes.

It has been noted that the “critical objectives for environment and development policies that follow from the concept of sustainable development include:

(i) reviving growth;

(ii) changing the quality of growth;

(iii) meeting essential needs for jobs, food, energy, water, and sanitation;

(iv) ensuring a sustainable level of population;

(v) conserving and enhancing the resource base;

(vi) reorienting technology and managing the risk; and

(vii) merging environment and economics in decision-making”.

Regarding suitable strategy, the report, Our Common Future, notes in its broadest sense that the strategy for sustainable development aims to promote harmony among human beings and between humanity and nature. In the specific context of the development and environment ….the pursuit of sustainable development requires:

(i) a political system that secures effective citizen participation in decision-making,

(ii) an economic system that is able to generate surpluses and technical knowledge on a self-reliant and sustained basis,

(iii) a social system that provides for solutions to the tensions arising from disharmonious development,

(iv) a production system that respects the obligation to preserve the ecological base for development,

(v) a technological system that can search continuously for new solutions,

(vi) an international system that fosters sustainable patterns of trade and finance, and

(vii) an administrative system that is flexible and has the capacity for self-correction. These requirements are more in the nature of goals that should underlie national and international action on development.

1. The Concept of Development and Underdevelopment

2. Process and Characteristics of Third World Countries

The term “Third World” originated during the Cold War, describing countries that were unaligned with either the capitalist First World or the socialist Second World. Over time, it has evolved to encompass nations facing socio-economic challenges.

1. Historical Context: The historical trajectory of Third World countries is marked by colonization, exploitation, and decolonization. Many nations endured centuries of colonial rule, resulting in the extraction of resources, economic subjugation, and cultural disruptions. The process of decolonization post-World War II was often tumultuous, with newly independent nations facing challenges in establishing stable governance structures.

2. Economic Characteristics: A defining characteristic of many Third World countries is economic underdevelopment. Factors such as colonial legacies, dependence on primary industries, unfavorable terms of trade, and external debt contribute to economic challenges. These nations often experience high levels of poverty, income inequality, and limited access to basic services like education and healthcare. The informal sector tends to be significant, reflecting a lack of formal job opportunities.

3. Dependency Theory: The Dependency Theory, often associated with Third World countries, posits that their economic underdevelopment is a result of their integration into the global capitalist system, where they serve as providers of raw materials and markets for developed nations. This unequal economic relationship perpetuates dependency, hindering the development of domestic industries and economic self-sufficiency.

4. Political Characteristics: Political instability and governance challenges are common in Third World countries. Historical factors, such as arbitrary colonial borders and the imposition of foreign systems, contribute to ethnic, religious, or tribal tensions. Autocratic rule, corruption, and weak institutions are recurrent issues, impacting the ability to implement effective policies and promote inclusive development.

5. Social Characteristics: Third World countries often grapple with social challenges, including inadequate healthcare, education, and social services. High levels of illiteracy, maternal and child mortality rates, and limited access to clean water and sanitation contribute to a cycle of poverty. Social inequality, exacerbated by economic disparities, is a pervasive issue, hindering social mobility.

6. Demographic Challenges: Population growth is a significant characteristic of many Third World countries. High birth rates, coupled with limited access to family planning resources, contribute to demographic challenges. Rapid urbanization often strains infrastructure, leading to informal settlements and slums, further exacerbating socio-economic issues.

7. Globalization and Inequality: While globalization has brought economic opportunities, it has also widened global inequalities. Many Third World countries face challenges in participating equitably in the global economy, often being relegated to roles as suppliers of cheap labor or raw materials. Trade imbalances and unequal access to technology and information contribute to this disparity.

8. Environmental Vulnerability: Third World countries are often disproportionately affected by environmental challenges such as climate change, deforestation, and resource depletion. Their vulnerability is exacerbated by limited capacity to adapt and mitigate the impacts, leading to issues like food insecurity, displacement, and environmental degradation.

9. Human Rights and Social Justice: Issues related to human rights, social justice, and marginalized populations are prevalent in Third World countries. These nations may struggle to address issues such as gender inequality, discrimination against minority groups, and challenges to freedom of expression.

10. Global Development Initiatives: Efforts to address the challenges faced by Third World countries involve global development initiatives, foreign aid, and collaborations. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), initiated by the United Nations, aim to address poverty, inequality, and environmental sustainability, providing a framework for international cooperation.

In conclusion, the process and characteristics of Third World countries are multifaceted, shaped by historical legacies, economic structures, political dynamics, and global interactions. Recognizing the diversity within this classification is crucial, as nations within the Third World exhibit unique challenges and opportunities on their paths to development. Addressing these challenges requires a comprehensive understanding of the interconnected factors influencing the socio-economic landscape of these countries.

3. Theories of Development

a. Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism is the idea that less government interference in the free market is the central goal of politics.

Neoliberals believe in a ‘small government’ which limits itself to enhancing the economic freedoms of businesses and entrepreneurs. The state should limit itself to the protection of private property and basic law enforcement.

Neoliberalism is most closely associated with Thomas Hayek and Milton Friedman, and the policies of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

Neoliberals advocate three main policies to increase the role of the private sector in the economy and society: privatization, deregulation and low taxation.

Some examples of Neoliberal Policies include:

- Lowering taxes on income, especially high income earners. When Thatcher came to power in 1997 she reduced income tax on the very highest earners from 83% to 60%.

- Lowering Corporation tax – The government reduced the main corporation tax from 28% in 2010 to just 21% in 2014.

- Privatising public services – Privatisation began under the Thatcher government of 1979 and continues today (2017). Britain’s rail, energy and water industries all used to be run by the state, but now they are run by private companies. Education and Health services are also being ‘privatised by stealth’, as more and more aspects of these services are contracted out to and run by private sector companies.

- Reducing the number of rules and regulations which constrain businesses: This involves national and local governments monitoring private businesses less: by reducing the number of ‘health and safety standards’ businesses need to conform to and doing fewer health and safety and environmental health inspections for example.

Further Background on Neoliberal Thought

Neoliberalism emerged in the 1950s as a reaction against ‘Keynesianism’ – the idea that nation states should play a significant role in managing free market capitalism through high taxation in order to provide public services such as unemployment benefit, free health care and education (‘the welfare state’).

Keynsianism itself was a development of the earlier doctrine of ‘Liberalism’ which believed that individual freedom was the central goal of politics. Obviously the question of what kind of society allows for the most or best freedom is open to debate, but by the 1950s a consensus had emerged that ‘liberty’ was best guaranteed if the state provided a high degree of regulation of the economy and investment in social welfare.

Neoliberals such as Friedman believed that this ‘Keynesian’ model of organising the economy was inefficient, one of the reasons being that it restricts the freedoms of successful economic actors to reinvest their money as they see fit, because the state takes it away from them through taxes and gives it to the less successful, which in turn can create a perverse situation in which society punishes success and rewards laziness.

Evaluations of Neoliberalism

Arguments for neoliberalism

- What right does the state have to tax money earnt through individual effort, innovation and risk?

- Neoliberals argue that the private sector run services more efficiently than the state sector.

- The argument for deregulation is that red-tape stifles business.

There are many critical voices of neoliberalism, mainly from the left and from within the green movement. Some of the main criticisms can be summarised as follows:

- Cutting taxes on the rich has resulted in greater inequality and a lower standard of public services, especially for the poor.

- Privatisation of public services has resulted in a massive transfer of wealth from the majority to the rich –

- Deregulation has made society less safe and stable – critics blame deregulation of the finance sector for the 2007 financial crash and the deregulation of health and safety legislation as being linked to the Grenfell Tower disaster.

Critical Points

It can be difficult to evaluate the impact of neoliberalism because the term is so broad, and there is actually quite a lot of disagreement over what it actually means.

Even if we just focus on the policy aspect of neoliberalism – and try to evaluate the impact of lowering taxation, privatisation and deregulation, you would almost certainly need to break these down and look evaluate the impact of each aspect separately, and maybe even subdivide each aspect further to evaluate properly.

b. Dependency Theory

Dependency Theorists argue that rich countries accumulated their wealth through exploiting poorer countries. Initially this was through colonialism and slavery, later on through neo-colonialism. To develop, poorer countries need to break free from these exploitative relations.

Andre Gunder Frank (1971), one of the main theorists within ‘dependency theory’ argued that developing nations have failed to develop not because of ‘internal barriers to development’ as modernisation theorists argue, but because the developed West has systematically underdeveloped them, keeping them in a state of dependency (hence ‘dependency theory’).

Dependency Theory is one of the major theories within the Global Development module, typically taught in the second year of A-level sociology.

The World Capitalist System

Frank argued that a world capitalist system emerged in the 16th century which progressively locked Latin America, Asia and Africa into an unequal and exploitative relationship with the more powerful European nations.

This world Capitalist system is organised as an interlocking chain: at one end are the wealthy ‘metropolis’ or ‘core’ nations (European nations), and at the other are the undeveloped ‘satellite’ or ‘periphery’ nations. The core nations are able to exploit the peripheral nations because of their superior economic and military power.

From Frank’s dependency perspective, world history from 1500 to the 1960s is best understood as a process whereby wealthier European nations accumulated enormous wealth through extracting natural resources from the developing world, the profits of which paid for their industrialisation and economic and social development, while the developing countries were made destitute in the process.

Writing in the late 1960s, Frank argued that the developed nations had a vested interest in keeping poor countries in a state of underdevelopment so they could continue to benefit from their economic weakness – desperate countries are prepared to sell raw materials for a cheaper price, and the workers will work for less than people in more economically powerful countries. According to Frank, developed nations actually fear the development of poorer countries because their development threatens the dominance and prosperity of the West.

Colonialism, Slavery and Dependency

Colonialism is a process through which a more powerful nation takes control of another territory, settles it, takes political control of that territory and exploits its resources for its own benefit. Under colonial rule, colonies are effectively seen as part of the mother country and are not viewed as independent entities in their own right. Colonialism is fundamentally tied up with the process of ‘Empire building’ or ‘Imperialism’.

According to Frank the main period of colonial expansion was from 1650 to 1900 when European powers, with Britain to the fore, used their superior naval and military technology to conquer and colonise most of the rest of the world.

During this 250 year period the European ‘metropolis’ powers basically saw the rest of the world as a place from which to extract resources and thus wealth. In some regions extraction took the simple form of mining precious metals or resources – in the early days of colonialism, for example, the Portuguese and Spanish extracted huge volumes of gold and silver from colonies in South America, and later on, as the industrial revolution took off in Europe, Belgium profited hugely from extracting rubber (for car tyres) from its colony in DRC, and the United Kingdom profited from oil reserves in what is now Saudi Arabia.

In other parts of the world (where there were no raw materials to be mined), the European colonial powers established plantations on their colonies, with each colony producing different agricultural products for export back to the ‘mother land’. As colonialism evolved, different colonies came to specialise in the production of different raw materials (dependent on climate) – Bananas and Sugar Cane from the Caribbean, Cocoa (and of course slaves) from West Africa, Coffee from East Africa, Tea from India, and spices such as Nutmeg from Indonesia.

All of this resulted in huge social changes in the colonial regions: in order to set up their plantations and extract resources the colonial powers had to establish local systems of government in order to organise labour and keep social order – sometimes brute force was used to do this, but a more efficient tactic was to employ willing natives to run local government on behalf of the colonial powers, rewarding them with money and status for keeping the peace and the resources flowing out of the colonial territory and back to the mother country.

Dependency Theorists argue that such policies enhanced divisions between ethnic groups and sowed the seeds of ethnic conflict in years to come, following independence from colonial rule. In Rwanda for example, the Belgians made the minority Tutsis into the ruling elite, giving them power over the majority Hutus. Before colonial rule there was very little tension between these two groups, but tensions progressively increased once the Belgians defined the Tutsis as politically superior. Following independence it was this ethnic division which went on to fuel the Rwandan Genocide of the 1990s.

An unequal and dependent relationship

What is often forgotten in world history is the fact that before colonialism started, there were a number of well-functioning political and economic systems around the globe, most of them based on small-scale subsistence farming. 400 years of colonialism brought all that to end.

Colonialism destroyed local economies which were self-sufficient and independent and replaced them with plantation mono-crop economies which were geared up to export one product to the mother country. This meant that whole populations had effectively gone from growing their own food and producing their own goods, to earning wages from growing and harvesting sugar, tea, or coffee for export back to Europe.

As a result of this some colonies actually became dependent on their colonial masters for food imports, which of course resulted in even more profit for the colonial powers as this food had to be purchased with the scant wages earnt by the colonies.

The wealth which flowed from Latin America, Asia and Africa into the European countries provided the funds to kick start the industrial revolution, which enabled European countries to start producing higher value, manufactured goods for export which further accelerated the wealth generating capacity of the colonial powers, and lead to increasing inequality between Europe and the rest of the world.

The products manufactured through industrialisation eventually made their way into the markets of developing countries, which further undermined local economies, as well as the capacity for these countries to develop on their own terms. A good example of this is in India in the 1930s-40s where cheap imports of textiles manufactured in Britain undermined local hand-weaving industries. It was precisely this process that Ghandi resisted as the leading figure of the Indian Independence movement.

Neo-colonialism

By the 1960s most colonies had achieved their independence, but European nations continued to see developing countries as sources of cheap raw materials and labour and, according to Dependency Theory, they had no interest in developing them because they continued to benefit from their poverty.

Exploitation continued via neo-colonialism – which describes a situation where European powers no longer have direct political control over countries in Latin America, Asia and Africa, but they continue to exploit them economically in more subtle ways.

Three main types of neo-colonialism:

Frank identified three main types:

Firstly, the terms of trade continue to benefit Western interests. Following colonialism, many of the ex-colonies were dependent for their export earnings on primary products, mostly agricultural cash crops such as Coffee or Tea which have very little value in themselves – It is the processing of those raw materials which adds value to them, and the processing takes place mainly in the West

Second, Frank highlights the increasing dominance of Transnational Corporations in exploiting labour and resources in poor countries – because these companies are globally mobile, they are able to make poor countries compete in a ‘race to the bottom’ in which they offer lower and lower wages to attract the company, which does not promote development.

Finally, Frank argues that Western aid money is another means whereby rich countries continue to exploit poor countries and keep them dependent on them – aid is, in fact, often in the term of loans, which come with conditions attached, such as requiring that poor countries open up their markets to Western corporations.

Dependency Theory: Strategies for Development

Dependency is not just a phase, but rather a permanent position. The historical colonialists and now the neo-colonialists continually try to keep poor countries poor so they can continue to extract their resources and benefit from their cheap labour, thus keeping themselves wealthy on the back of exploitation.

It thus follows that the only way developing countries can escape dependency is to break away from their historical oppressors.

There are different paths to development with differing emphasis on the extent to which developing countries need to become independent of their historical colonial masters, their neo-colonial ‘partners’ or from the entire global capitalist system itself!

- Isolation, as in the example of China from about 1960 to 2000, which is now successfully emerging as a global economic superpower having isolated itself from the West for the past 4 decades.