BAA 322

Ancient Indian Paleography and Epigraphy

Semester – VI

Q1. Ancient Indian History writing is incomplete without uses of inscriptions. Discuss.

The greatest handicap in the treatment of history of ancient India, both political and cultural, is the absence of a definite chronology.

The literary genius of India, so fertile and active in almost all branches of study, was somehow not applied to chronicling the records of kings and the rise and fall of the states.

Ancient India did not produce historians like Herodotus and Thucydides of Greece or Levy of Rome and Turkish historian Al-beruni. We have a sort of history in the Puranas. Though encyclopedic in contents, the Puranas provide dynastic history up to the beginning of the Gupta rule.

They mention the places where the events took place and sometimes discuss their causes and effects. Statements about events are made in future tense, although they were recorded much after the happening of the events. Thus inscriptions and coins become very important to reconstruct early Indian history.

Inscriptions were carved on seals, stone pillars, rocks, copper plates, temple walls and bricks or images. In the country as a whole the earliest inscriptions were recorded on stone. But in the early centuries of Christian era copper plates began to be used for the purpose. The earliest inscriptions were written in Prakrit language in the 3rd century BC. Sanskrit was adopted in the second century AD.

Inscriptions began to be composed in regional languages in the 9th and 10th centuries. Most inscriptions bearing on the history of Maurya, Post-Maurya and Gupta times have been published in a series of collection called “Corpus Inscription Indecorum”.

The earliest inscriptions are found on the seals of Harappa belonging to about 2500 B.C. and written in pictographic script but they have not been deciphered. The oldest inscription deciphered so far was issued by Ashoka in third century BC. The Ashokan inscriptions were first deciphered by James Prince in 1837.

We have various types of inscriptions. Some convey royal orders and decisions regarding social, religious and administrative matters to officials and people in general. Ashokan inscription belong to this category, others are routine records of the followers of different religious. Still other types eulogize the attributes and achievements of the kings and their persons.

The inscriptions engraved by emperors or kings are either prosthesis composed by court writers or grants of land assigned to individuals. Among the prismatic of emperors, the most prominent are the prasharti of Samudra Gupta engraved on Ashokan pillar at Allahabad. This was prepared by his court poet, Harisena, the Hathigumpa-Prashasti inscription of king Kharavela of Kalinga.

Some of the notable inscriptions are – the Nasik inscription of King Gautami Balasree, the Gwalior inscription of King Bhoja, the Girnar inscription of King Rudradaman, the Aihole inscription of the Chalukaya King Pulkesinll, the Bhitri and Nasik inscriptions of the Gupta ruler Skandia Gupta and the Deopara inscription of the Sena ruler Vijaya Sen. The inscriptions which were used for the grants of lands were mostly engraved on copperplates.

These inscriptions besides many more, of private individuals or local officers have furnished us with the names of various kings, boundaries of their kingdoms and sometimes useful dates and clues to many important events of history.

Thus inscriptions have been found very much useful in finding different facts of the history of ancient India. The history of Satavahana rulers is fully based on their inscriptions. In the same way, the inscriptions of the rulers of South India such as that of Pallava, the Chalukyas, the Rashtrakutas, the Cholas, and the Pandayas have been of great help in finding historical facts of the rule of their respective dynasties. Certain inscriptions found outside India have also helped in finding facts concerning the history of ancient India. One among such inscriptions is that of Bhagajakoi in Asia Minor, which was inscribed in 1400BC.

The study of coins, called numismatics, is considered as the second most important source for reconstructing the history of India. Coins are mostly found in hoards. Many of these hoards containing not only Indian coins but also those minted abroad, such as Roman coins have been discovered in different parts of the country. Coins of major dynasties have been catalogued and published.

The punched mark coins are the earliest coins of India and they bear only symbols on them. These have been found throughout the country. But the later coins mentioned the name of kings, gods and dates. The areas where they are found indicate the region of their circulation. This has enabled us to reconstruct the history of several ruling dynasties, especially of the Indo-Greeks. Coins also throw significant light on economic history.

Some coins were issued by the guilds and merchants and goldsmiths with the permission of the rulers. This shows that craft and commerce had become important. Coins helped transactions on a large scale and contributed to trade. We get the largest number of coins in post-Maurya times.

These were made of lead, potion, copper, bronze, silver and gold. The Guptas issued the largest number of gold coins. This indicates that trade and commerce flourished during post- Maurya and a good part of Gupta times. But the fact that only a few coins belonging to post-Gupta times indicate the decline in trade and commerce in that period.

In conclusion, careful collection of materials derived from texts, coins, inscriptions, archaeology etc. is essential for historical construction. These raise the problem of relative importance of the sources. Thus, coins and inscriptions are considered more important than mythologies found in the Epics and the Puranas.

Q2. Discuss the Historical importance of ‘Mehraulli Iron Pillar Inscription of Chandra.

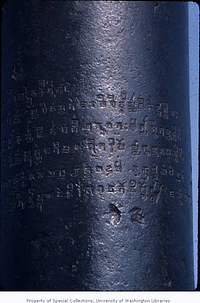

Mehrauli inscription praises the Gupta emperor Chandragupta Vikramaditya’s achievements. The iron pillar of Chandragupta dates from the late fourth to early fifth century A.D. It is situated in the Qutb Mosque’s courtyard. It is thought to have had the emblem of the mythical bird Garuda, the Guptas’ symbol, at the top, but it is now missing.

Mehrauli Inscription / Garuda Pillar – Background

- The Mehrauli Iron Pillar was originally located on a hill near the Beas River and was transported to Delhi by a Delhi king.

- This pillar attributes the victory of the Vanga Countries to Chandragupta, who fought alone against a confederacy of opponents gathered against him.

- It also praises him for defeating the Vakatkas in a battle that spanned Sindhu’s seven mouths.

- The Mahrauli Iron Pillar is a historical landmark that entices visitors with its intriguing iron structure that has not corroded since its creation over 1600 years ago.

- Despite being exposed to the elements, the Iron Pillar remains robust, serving as a great illustration of ancient India’s scientific and engineering progress.

- Archaeologists and materials scientists are still working to answer one of the world’s oldest riddles.

- Iron Pillar, which rises magnificently at a height of 24 feet, is located within the Qutub Complex, which also houses the famed Qutub Minar. It is located in the Qutb Complex, in front of the Quwwatul Mosque.

- It contains verses composed in the Sanskrit language, in shardulvikridita metre.

Mahrauli Inscription / Garuda Pillar – History

- According to academics, the Mehrauli Iron Pillar was built during the early Gupta dynasty (320-495 AD). This conclusion is based on the workmanship style and inscription on the pillar, as well as the language.

- Scholars have discovered the name “Chandra” in the third stanza of the inscription on the Iron pillar, which signifies kings of the Gupta Dynasty.

- The king is identified as Chandragupta II (375-415 CE) who was the son of King Samudragupta.

- Chandragupta-II of the Gupta dynasty named this pillar Vishnupada in honor of Lord Vishnu.

- According to one popular theory, the Iron Pillar was erected on top of a hill in Madhya Pradesh called Udaygiri, from which King Iltutmish (1210-36 AD) carried it to Delhi following his triumph.

- According to some experts, King Anangpal II, Tomar King, lifted the Delhi Iron Pillar and installed it in the main shrine at Lal Kot in New Delhi around 1050 AD.

- When King Prithviraj Chauhan, Anangpal’s grandson, was defeated by the Muhammad Ghori army in 1191, Qutb-ud-din Aibak erected the Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque at Lal Kot.

- The pillar was then relocated from its original site in front of the mosque to its current location.

Features

Mehrauli Inscription / Garuda Pillar – Features

- Mehrauli’s Iron Pillar stands at a height of 7.2 metres. It rests on a 48-centimetre-diameter intricately carved foundation that weighs 6.5 tonnes.

- The pillar’s summit is embellished with carvings. It also includes a deep hole that is claimed to be the foundation where Hindu Lord Garuda‘s statue was placed. Inscriptions are engraved onto an iron pillar.

- The most intriguing aspect of Iron pillar architecture is that it has not rusted in over 1600 years of exposure to the elements.

- Some of the inscriptions on the iron pillars hint to its origin. However, the original place where it was created is still being investigated.

- At roughly 400 cm from the present ground level of the pillar, there is a conspicuous depression in the centre of the otherwise smooth Iron Pillar.

- It is reported that the devastation was caused by the close-range fire of cannonballs.

Mehrauli Inscription

Conclusion

The Mehrauli iron pillar, also known as the Delhi iron pillar or Lohe ki Lat, is located within the Qutb complex. It was constructed in the fourth or fifth centuries CE and moved to this position 800 years later during the Delhi Sultanate period. The Pillar is remarkable for its rusty state, despite being made of 99% iron and having been built in the 5th century CE, giving it a lifespan of roughly 1600 years. It is thought to have featured the insignia of the mythological bird Garuda, the Guptas’ symbol, at the top, but it is now lost.

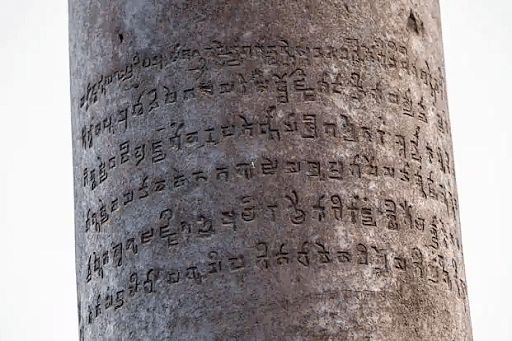

Q3. Throw light on the development of Brahmi Script from Mauryan to Kushana Period with examples.

Brahmi script is one of the oldest writing systems, having been used in the Indian subcontinent and Central Asia during the final centuries BCE and the early centuries CE. Some believe that Brahmi was derived from the modern Semitic script, while others believe it was an Indus script. The Brahmi is the ancestor of all surviving Indic scripts in South East Asia. In India writing developed during the time of the Indus Valley Civilization. Brahmi script is credited with giving rise to several modern scripts found in South and Southeast Asia.

Origin and Evolution

Various schools of thought are prevalent regarding the origin of Brahmi script, some of which are discussed below:

- Georg Bühler argued that Brahmi was initially derived from the Semitic script that was later used by the Brahman scholars as appropriate for Sanskrit and Prakrit.

- Professor K Rajan thought that the ancestor of the Brahmi script is a combination of symbols present on graffiti marks in various places in Tamil Nadu.

- This argument ha has been supported by excavations at Mangudi, Tamil Nadu

- Some believe that Brahmi has its origin from the Indus script used during Indus Valley Civilization.

- Some think that the Brahmi script has its origin earlier to the 3rd century BCE.

- The above argument is supported by the existence of Brahmanas, which were attached to the Vedic literature during the 6th century BCE.

- This belief was further strengthened by the discovery of pottery belonging to the 450-350 BCE period from Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka.

Brahmi Script

Characteristic Features of Brahmi Script

- Initially, Brahmi was referred to as the “pin-man” script or the “stick figure” script, a clear reference to the appearance of its letters.

- The best-known Brahmi inscriptions are the rock-cut edicts of Ashoka, which date from 250–232 BCE and are found in north-central India.

- James Prinsep deciphered the script in 1837.

- Brahmi is typically written left to right.

- Brahmi is an abugida, which means that each letter represents a consonant, while vowels are written with obligatory diacritics called matras in Sanskrit unless the vowels begin a word.

- Its writing units include different types of syllables such as CV, CCVV, etc

- It is an alpha syllabic writing style.

- The V and C components of the Brahmi script are distinct.

- In the north and central India it represents the Prakrit language.

- In southern India it represents Tamil-a Dravidian language.

- It became widespread in usage from the 2nd century BCE.

- It evolved into various regional forms.

- It uses three vowels a; I; u.

Features of Brahmi Script

Usage

Usage of Brahmi Script

- It found its use on various Ashokan inscriptions.

- During the Mauryan period it was also used on carved rocks, caves, stones slabs, etc.

- It was used on copper plates.

- With the spread of Buddhism it was used on various structural monuments.

- From the 2nd century BCE it was also used on coins.

- It was also used on ceramic surfaces to suggest ownership of the item.

Various Scripts

Various Scripts Derived from Brahmi

- It became an ancestor to several languages as it could be modified to suit the phonetics of different languages.

- Various languages across the south and southeast Asia such as Gurmukhi, Kanarese, Sinhalese, Telugu, etc. trace their origin to Brahmi script.

- Punctuation is rarely used in Ashokan Brahmi.

- It developed into a rounded form in southern India.

- In northern India it was commonly used as a regularized form.

- Northern Brahmi in turn gave rise to the Gupta script called Late Brahmi.

- The Gupta script gave rise to Siddham (6th century), Sharada (9th century), and Nagari (10th century).

- Southern Brahmi is responsible for the origin of Pallava Grantha (6th century), Vatteluttu (8th century) scripts.

Conclusion

While Brahmi’s influence appears to have been limited to areas with a strong early Indian influence, the Baybayin script system of the Philippines is an exception. Brahmi’s colossal influence can still be felt today, from modern-day Punjab and Kashmir to South-East Asia and beyond.

Q4. Bringout the cultural importance of ‘Besanagar Pillar Inscription’ of Heliodorus.

The Heliodorus pillar is a stone column that was erected around 113 BCE in central India in Besnagar (near Vidisha, Madhya Pradesh). The pillar was called the Garuda-standard by Heliodorus, referring to the deity Garuda. The pillar is commonly named after Heliodorus, who was an ambassador of the Indo-Greek king Antialcidas from Taxila, and was sent to the Indian ruler Bhagabhadra. A dedication written in Brahmi script was inscribed on the pillar, venerating Vāsudeva, the Deva deva the “God of Gods” and the Supreme Deity. The pillar also glorifies the Indian ruler as “Bhagabhadra the savior”. The pillar is a stambha which symbolizes joining earth, space and heaven, and is thought to connote the “cosmic axis” and express the cosmic totality of the Deity.

The Heliodorus pillar site is located near the confluence of two rivers, about 60 kilometres (37 mi) northeast from Bhopal, 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) from the Buddhist stupa of Sanchi, and 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) from the Hindu Udayagiri site.

The pillar was discovered by Alexander Cunningham in 1877. Two major archaeological excavations in the 20th-century have revealed the pillar to be a part of an ancient Vāsudeva temple site. Aside from religious scriptures such as the Bhagavad Gita, the epigraphical inscriptions on the Heliodorus pillar and the Hathibada Ghosundi Inscriptions contain some of the earliest known writings of Vāsudeva-Krishna devotion and early Vaishnavism and are considered the first archeological evidence of its existence. The pillar is also one of the earliest surviving records of a foreign convert into Vaishnavism. Alternatively, making dedications to foreign gods was only a logical practice for the Greeks, intended to appropriate their local power. This cannot be regarded as a “conversion” to Hinduism.

Q5. Throw light on the History of Chalukya dynasty upto the Pulakshin II on the basis of the ‘Aihole Inscription’.

The Aihole Inscription, also known as the Aihole prashasti, is a nineteen line Sanskrit inscription at Meguti Jain temple in Aihole, Karnataka, India. An eulogy dated 634–635 CE, it was composed by the Jain poet Ravikirti in honor of his patron king Pulakesin Satyasraya (Pulakeshin II) of the Badami Chalukya dynasty. The inscription is partly damaged and corrupted – its last two lines were added at a later date.

Since the 1870s, the inscription was recorded several times, revised, republished and retranslated by Fleet, Kielhorn and others. The inscription is a prashasti for the early Western Chalukyas. It is notable for its historical details mixed in with myth, and the scholarly disagreements it has triggered. It is also an important source of placing political events and literature – such as of Kalidasa – that must have been completed well before 634 CE, the date of this inscription.

The Aihole inscription of Ravikirti, sometimes referred to as the Aihole Inscription of Pulakesin II, is found at the hilltop Meguti Jain temple, about 600 metres (1,969 ft) southeast of Aihole town’s Durga temple and archaeological museum.

The Aihole inscription is found on the eastern side-wall of the Meguti Jain temple. Aihoḷe – also known as Ayyavole or Aryapura in historic texts – was the original capital of Western Chalukyas dynasty founded in 540 CE, before they moved their capital in the 7th-century to Badami. Under the Hindu dynasty of the Badami Chalukyas, the Malprabha valley sites – such as Aihole, Badami, Pattadakal and Mahakuta – emerged as major regional center of arts in early India and a cradle of Hindu and Jain temple architecture schools. They patronized both Dravida and Nagara styles of temples. Meguti Jain temple is one among the hundreds of temples built in that era, but one built many decades after the famed Badami cave temples and many others.

Fleet was the first to edit and publish a photo-lithograph of the Aihole inscription in 1876. However, errors led to another visit to Aihole and then Fleet published an improved photo-lithograph, a revised version of the text with his translation in 1879. The significance of the inscription and continued issues with reconciling its content with other inscriptions, attracted the interest of other scholars. In 1901, the Sanskrit scholar Kielhorn re-edited the inscription at the suggestion of Fleet. He published yet another improved version of the photo-lithograph.

Q6. Discuss the contents of Kahaum stone Pillar inscription of Skandgupta.

- This is the inscription of the Gupta ruler Skandagupta.

- In this inscription, Skandagupta has been called “Shukraditya”.

- It also describes 5 Jain Tirthankaras.

- Information about the local administration is also available in this record.

Kahaum pillar is an 8 m (26 ft 3 in) structure located in Khukhundoo in the state of Uttar Pradesh, and dates to the reign of Gupta Empire ruler Skandagupta. The 5th century an 8 metres (26 ft) pillar known as Kahaum pillar was erected during the reign of Skandagupta. This pillar has carvings of Parshvanatha and other tirthankars with Jain Brahmi script.

Kahaum pillar is a grey-sandstone was erected during the reign of Skandagupta, Gupta Empire. According to inscription of the pillar, the pillar was erected by the Skandagupta in the Jyeshtha month of year 141 of the Gupta era (A.D. 460–61). The pillar was erected by Skandagupta upon receiving counsil from Madra.

There is a 0.673 by 0.51 metres (2 ft 2.5 in by 1 ft 8.1 in) on the pillar with writing with characters belonging to eastern variety of Gupta alphabet similar to that of Samudragupta inscription of Allahabad Pillar. The inscription is written in Sanskrit language, and written in verses except for the first word, siddhaṁ. The inscription defines reign of Skandagupta as peaceful and describes him as “commandar of a hundred kings”. The inscription also has an adoration to Arihant of Jainism.

There is carving of five Jain Tirthankara in kayotsarga posture — one in a niche square face, two below the circular stone and two on the pinnacle of the column. These images are identified to be of Rishabhanatha, Shantinatha, Neminatha, Parshvanatha and Mahavira. According to inscription, these images were carved by Madra who is described as devotee of dvija, guru and yati.

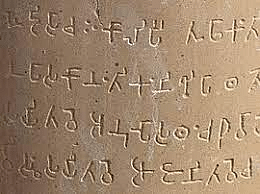

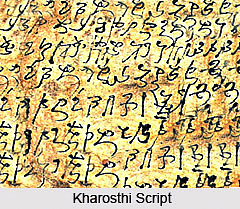

Q7. Kharoshthi Script.

The Kharosthi script (3rd Century BC – 3rd Century AD) is an ancient script used to write Gandhari Prakrit and Sanskrit in ancient Gandhara (present-day Afghanistan and Pakistan). It is a sister script to Brahmi and was deciphered by James Princep. Since early times Kharosthi has been one of the major scripts of the Indian sub-continent. It comes second in popularity to Brahmi script.

Origin of Kharosthi Script

Different theories are put forward regarding the origin of the Kharosthi script some of which are discussed below:

- The earliest evidence has been found from major rock edicts of Ashoka.

- Between the first century BCE to the third century CE it was in use by Kushanas.

- It was put forward by Buhler. Kharosthi script was related to the parts of the Indian subcontinent that were ruled by Persians.

- Kharosthi script has various alterations done from Aramic prototypes.

- It is also believed by B.N. Mukherjee said that this script was created by the Achaemenids during the 5th – 4th century BC.

- It was originally adapted for the local language of common people but was later adapted by foreign conquerors to connect with the local population.

Kharosthi Script

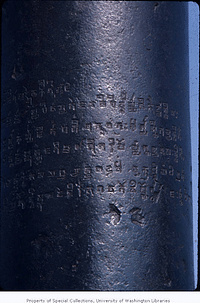

Discovery of Kharosthi Script

- In Lalitavistara, a 3rd century BCE text written in Kharosthi, it is mentioned as second to Brahmi script.

- It was first encountered in edicts of Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE.

- It was first discovered on coins of the 19th century from the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent.

- Kanishka inscriptions from 1830 to 1834 were found at Manikiyala in Pakistan with Kharosthi script.

- It was called Bactrian Pahlavi by James Prinsep as it was found on various Bactrian coins.

- James Princep deciphered 11 out of the 12 letters of Kharosthi script, rest were done by C. Lassen, A. Cunningham, etc.

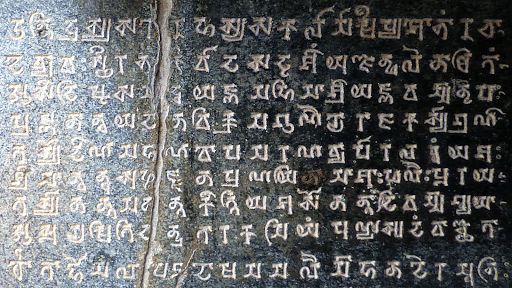

Inscriptions in Kharosthi

Distribution

Distribution of Kharosthi Script

- This script was used in various parts of the Gandhara Kingdom such as Indus, Swat, and Kabul river valleys.

- Kharosthi scripts have also been discovered from Qunduz in north Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan.

- These have also been discovered from Kumrahar (Patna) and Bharhut (a famous stupa site in Madhya Pradesh).

- The Minor Rock Edicts I and II of Asoka in Karnataka, the name of the scribe Chapada is mentioned in Kharosthi.

- It also found its use in Central Asia such as in the Shan-shan kingdom on the Tarim Basin.

- Due to patronage by Kushana rulers it was also found in areas outside Gandhara.

Characteristic Features

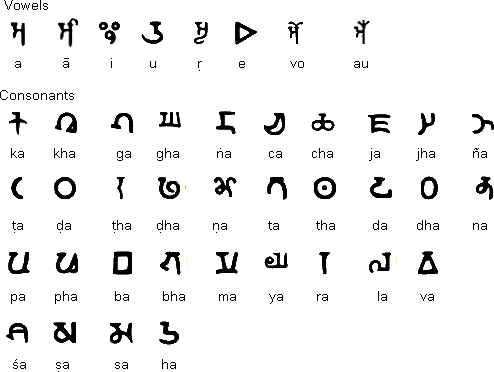

Characteristic Features of Kharosthi Script

- It is a middle Indo-Aryan dialect.

- It is written from right to left.

- It includes numbers similar to Roman numerals.

- It mostly consists of the use of Indian, Greek, and Iranian words.

- It consists of only one basic form of the vowel.

- In this script medial vowels are also expressed.

- Its original letters were based on Arabic and the remaining have evolved with the addition of diacritic marks.

- It is cursive.

- It is a top-oriented script as each letter has a character on its upper part.

Conclusion

Kharosthi script was used in the Indian subcontinent by rulers to establish a connection with the local population, for use on religious relics, etc. It was initially confined to the Gandhara region. But with the spread and movement of people, it reached Central Asia, some parts of northern India, and even South East Asia. Thus in the last decade of the nineteenth century ‘Arian Pali’ was identified as ‘Kharosthi’ scripts.

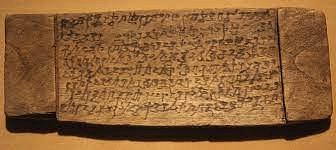

Q8. Gupta Script.

Gupta script is also known as Late Brahmi Script. It was used for writing Sanskrit language during the Gupta period. It was used from 320 to 550 AD. The Nagari, Sharada, and Siddham scripts all descended from the Gupta script, which descended from Brahmi. These scripts gave rise to many of India’s most important scripts, including Devanagari, Gurmukhi script for Punjabi, Assamese script, Bengali script, and Tibetan script. All of these descendants of the Brahmi script are referred to as Brahmic scripts.

Origin of Gupta Script

- It traces its origin from Brahmi script.

- It gave rise to Sarada, Siddham and Devanagari scripts.

- It became widespread in Gupta empire as a result of which it also underwent regional variations.

- These are found on gold coins, stone and iron pillars from Gupta dynasty.

- It includes Prayagraj Prasasti by Harisena.

Gupta Script

Characteristics of Gupta Script

- Each letter is represented by a consonant and an inherent vowel.

- There is absence of separate vowel letters.

- Letters are combined together based on their pronunciation.

- It is written from left to right in horizontal lines.

- In this script shapes and forms of diacritic are different.

- This script consists of 37 letters.

- Independent vowels are 5 in number, whereas consonants are 32.

- Combination of consonants called conjunct consonants are also present.

Vowels and Consonants in Gupta Script

Conclusion

The Gupta Empire was a period of religious and scientific developments. This era has records of various inscriptions on coins, pillars, etc. Gupta script was evolved from the Brahmi script and it further is considered to be responsible for emergence of Sarada, and Siddam scripts.

Q9. Write ‘Jna’ alphabet in Mauryan Brahmi Script.

Q10. Where Mansehra inscription has been found?

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan

Mansehra Rock Edicts are fourteen edicts of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka, inscribed on rocks in Mansehra in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. The edicts are cut into three boulders and date back to 3rd century BC and they are written in the ancient Indic script of Gandhara culture, Kharosthi. The edicts mention aspects of Ashoka’s dharma. The site was submitted for inclusion in the World Heritage Sites and is currently in the tentative list.

Q11. What was the main title of Buddhamitra in Saranath inscription of Kanishka?

Bala Bodhisattva

Q12. Convert 634 A.D. into saka era.

556 Saka Year

Q13. Which seasoned is mentioned in Saranath inscription of Kanishka?

At the back of the base of the statue: “In the 3rd year of the Maharaja Kanishka, the 3rd (month) of winter, the 23rd day, on this (date specified as) above has (this gift) of Friar Bala, a master of the Tripitaka, (namely an image of) the Bodhisattva and an umbrella with a post, been erected.”

Q14. Who edited the book “Select inscriptions”?

Sircar,Dines Chandra dc

Q15. Lumbini Pillar Inscription.

The Lumbini pillar inscription, also called the Paderia inscription, is an inscription in the ancient Brahmi script, discovered in December 1896 on a pillar of Ashoka in Lumbini, Nepal by former Chief of the Nepalese Army General Khadga Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana under the authority of Nepalese government and assisted by Alois Anton Führer. Another famous inscription discovered nearby in a similar context is the Nigali-Sagar inscription. The Lumbini inscription is generally categorized among the Minor Pillar Edicts of Ashoka, although it is in the past tense and in the ordinary third person (not the royal third person), suggesting that it is not a pronouncement of Ashoka himself, but a rather later commemoration of his visit in the area.

Q16. Write the definition of ‘Palacegraphy’ and critically examine the various theories of the origin of Brahmi script.

Palaeography or paleography is the study of historic writing systems and the deciphering and dating of historical manuscripts, including the analysis of historic handwriting. It is concerned with the forms and processes of writing; not the textual content of documents. Included in the discipline is the practice of deciphering, reading, and dating manuscripts, and the cultural context of writing, including the methods with which writing and books were produced, and the history of scriptoria.

The discipline is one of the auxiliary sciences of history. It is important for understanding, authenticating, and dating historic texts. However, it generally cannot be used to pinpoint dates with high precision.

Origin of Brahmi

In spite of nearly two centuries of research on the history of writing in India, the precise origin of the Brahmi script, the principal script of early India, from which all the later South Asian and Southeast Asian scripts developed, has still remained improperly known. The origin of the Brahmi script has been a major debate in the realm of Indian epigraphy ever since its decipherment in the first half of the nineteenth century. Like most of the ‘origin theories’ scholarly world dealing with the origin of the Brahmi script is also divided into two ‘camps’, one advocating for an essentially Indian origin of the script, while the other providing evidence in support of an extraneous influence and/or derivation. Although systematic attempts at reconsidering the origin of the Brahmi script was initiated by scholars like Georg Buhler and G.H. Ojha, attempts were made at explaining the possible roots of this scripts well predate the researches of these two scholars. Recently Richard Salomon has made a comprehensive review of the literature dealing with the problem of the origin of this script. Here we may summarize the discussion on the issue in the light of the thorough review made by Salomon.

Theories of Indigenous Origin:

Among the early scholars dealing with the issue, Alexander Cunningham suggested that Brahmi had its root from a pictographic-logographic script and tried to explain the palaeography of some of the Brahmi letters in the light of a kind of ‘pictographic etymology’. His theory was, however, criticized for obvious reasons by Isaac Taylor and others.

G.H. Ojha and later, following him, R.B. Pandey and T.P. Verma suggested that Brahmi of course had an indigenous genesis, though the precise route of the development leading to what is seen in the Asokan inscriptions explained by them. In the words of Richard Salomon:

G. H. Ojha…was highly critical of Buhler’s Semitic derivation and was inclined to doubt any foreign derivation, though he avoided denying the possibility altogether. Ojha concluded that an indigenous origin is most likely, although the precise source and development cannot be specified. R. B. Pandey argued more categorically in favor of an indigenous origin, concluding that “the Brahmi characters were invented by the genius of the Indian people who were far ahead of other peoples of ancient times in linguistics and who evolved vast Vedic literature involving a definite knowledge of alphabet”. Since the discovery in the 1920s and subsequent decades of extensive written artifacts of the Indus Valley civilization dating back to the third and second millennia B.C., several scholars have proposed that the presumptive indigenous prototype of the Brahmi script must have been the Indus Valley script or some unknown derivative thereof. This possibility was first proposed by S. Langdon in 1931, supported by G. R. Hunter, and endorsed by several later authorities, most significantly by D. C. Sircar.’

It is important to note here that a protohistoric connection of the Brahmi script was also offered by B.B. Lal on the basis if some graffiti marks on pottery from a site called Vikramkhol and these were taken by Lal to argue an early antiquity of the Brahmi script, the ‘Vikramkhol inscriptions’ being explained as ‘missing links’ between Harappan and Early Brahmi scripts. However, Lal’s theory was not generally accepted. Some recent scholars have argued that Brahmi, as we see in the inscriptions of Asoka, must have had underwent preceding stage of development and refinement from a pre-existing system of writing, particularly in view of the uniform and monumental version of the script appearing in the Asokan edicts. There are also proposals based on textual reference in Buddhist, Jain and Classical literature that Indian knew the art of writing well before the Maurya period.

Theories of Foreign Origin:

Compared to the school of Indian origin, the group supporting a non-Indian origin of the script has more supporting evidence. This school, however, is again subdivided into a number of sub-schools. James Prinsep believed that Brahmi had evolved from the Greek script, obviously on the basis of the long-drawn cultural and political contacts of India with the Macedonian world. But Prinsep was only able to explain the palaeography of a few Brahmi letters as direct derivatives of Greek. A more refined theory of Greek derivation was later proposed by J. Halevy. However, the theory gained importance recently when Harry Falk accepted partially the proposal of Halevy and suggested a modified argument, explaining the derivation of the earliest version of Brahmi from and mixed Kharosthi and Greek progenitor. But here again, the problem was that none of these latter scholars could explain the systemic on which their theories of derivation rest.

Scholars debating on the origin of Brahmi from a probable Semitic origin are, likewise, divided into two subgroups: those supporting a likely South Semitic origin and the others favouring the North Semitic derivation. Supporters of the South Semitic derivation have based their argument more on the direction of writing than the actual palaeographic features, as Salomon has rightly pointed out. Different branches of the North Semitic have been proposed by different authorities to have been the precursor of the early Brahmi script. The first scholar to have underlined a probable connection between Phoenician and Indian scripts was Ulrich Friedrich Kopp who as early as 1821 had prepared comparative tables in the light of forms of modern Indian scripts and their link with Phoenician. The most systematic and authentic study of the theme was undertaken by Albrecht Weber who made a thorough comparison of the Phoenician and early Brahmi. The theory was later presented in a more articulated and categorical frame by Buhler. An Aramaic origin of Brahmi was first suggested by A.C. Burnell in the year 1874. In terms of palaeographic development, a connection between early Brahmi and Aramaic is more favoured than that of Phoenician.,

Richard Salomon has rightly observed that instead of looking into the problem of origin of the Brahmi script in terms of the patterns of derivation of individual letter forms, it is important to consider the systemic that govern the

‘The system of postconsonantal diacritic vowel indicators looks like a natural adaptation of the Semitic consonant-syllabic script for use in Indian languages. Similarly, the evident development of the retroflex consonants as modified forms of the corresponding dentals suggests an adaptation of a non-Indie prototype, since in an originally Indian system one would have expected independent signs for the two classes from the very beginning.’

Q17. Why the inscriptions are important as the source of History? Explain.

Inscriptions are more important than coins in historical reconstruction. The study of inscriptions is called ‘epigraphy’, and the study of old writing is called ‘palaeography’. Inscriptions are writings carved on seals, stone pillars, rocks, copper plates, temple walls and bricks or images.

The vast epigraphic material available in India provides the most reliable data for studying history. Like coins, inscriptions are preserved in various museums, but the largest number is under the Chief Epigraphist at Mysore.

The earliest inscriptions found were written in Prakrit in the 3rd century bc. Sanskrit became an epigraphic medium in the 2nd century ad. Regional languages also came to be employed in inscriptions from the 9th-10th centuries onwards.

Many inscriptions pertaining to the history from the Maurya to Gupta times have been published in a series of collections called ‘Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum’. In South India, topographical lists of inscriptions have been published.

The earliest inscriptions are found on the seals of Harappa, which, however, remain undeciphered. The oldest inscriptions deciphered so far are the Prakrit inscriptions, in Brahmi and in Kharosthi, of Asoka (third century bc).

Inscriptions are writings made on hard materials such as rocks, wood, bricks or metals. The writings were common during the early ages and were used for a series of reasons. Samudra Gupta was a leader of the Gupta Empire in ancient India and he is also referred to as the father of inscriptions. Epigraphy is the study of inscriptions. Sir Alexander Cunningham is known to be the father of epigraphy. Epigraphers reconstruct, translate and date inscriptions. After that, historians come in to interpret and determine the events that led to the inscriptions.

Most of the time, the epigraphers happen to be historians as well. Early inscriptions and epigraphy have lots of importance and relevance to the world today. Below are some of the advantages that legends have brought along.

PROPER DATING OF EVENTS

Once epigraphers come across an inscription, the first thing they do is to date the writings on the rock, cave or metal. The dating gives an approximate time that the writings were engraved. After the legends have been translated, historians can keep records of the events according to time. The inscriptions mostly tell stories of what happened ages ago and are therefore perfect for filling some gaps in history. Without proper dating, historians would not have reliable records.

MORE INFORMATION

Early inscriptions could either be formal or informal. The official legends keep records of the kings and how they managed to conquer battles. The official writings also cover what happened in the various kingdoms during that era. Informal inscriptions, on the other hand, give small details such as the names of the kings and queens, their habits, what they preferred to do in their spare time and sometimes their favourite foods. Such details enable historians to form profiles of the people they are dealing with and therefore tell the stories better.

Where inscriptions are made sheds a lot of light on the lifestyle of the people. There are writings found in caves. From this, historians can tell that the people in that era lived in caves. At other times, the records are found on buildings made of bricks. Such information shows that bricks had been invented and people had moved from living in caves. The same goes for inscriptions made on wood or metals. Apart from the information itself, the location of the legends gives a clearer picture of the society.

ANCIENT CULTURE AND BELIEFS

The early inscriptions could be writings or drawings, giving detailed information on the happenings. Significant events, such as religious practices and cultural events, were not left out. Taboos and behaviour that qualified as ideal were also listed. The information left behind helps people understand the lifestyle of the people better in terms of their culture and beliefs. Knowing this, people can decipher the events and also classify if the actions of the ancient kings were commendable or not.

SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC ACTIVITIES

Apart from the political events that occurred, inscriptions also tell stories about the social and economic activities people indulged themselves in. Things like food grown for commercial purposes and the mediums of exchange of goods and services were also recorded. Social events and what people wore during that time are also important details that are not left out in the inscriptions. Such features are essential while trying to understand what happened ages ago.

ACCURATE INFORMATION

Inscriptions are the most accurate and reliable source of information about ancient times. Since the reports were written as events happened, the records become the perfect baseline to put together the happenings of the era. The inscriptions hint on all the major transitions and occurrences in history and therefore rule out the speculation aspect. With accurate information, historians ensure that one uniform story spreads throughout the world. Without this, there would exist many inaccurate stories about the past.

LEARNING NEW LANGUAGES

Early inscriptions were written in different languages depending on the empire. For epigraphers, this becomes a perfect opportunity for them to learn new words. The deciphering of the inscriptions is essential and has to be done accurately. Therefore, before translating what the legends say, epigraphers have to ensure that their mastery of the language is impeccable. Also, translation is done by a team of epigraphers to ensure they get everything right.

Q18. Who was Chandra? Discuss his achievements on the basis of Mehrauli Pillar Inscription.

Mehrauli inscription praises the Gupta emperor Chandragupta Vikramaditya’s achievements. The iron pillar of Chandragupta dates from the late fourth to early fifth century A.D. It is situated in the Qutb Mosque’s courtyard. It is thought to have had the emblem of the mythical bird Garuda, the Guptas’ symbol, at the top, but it is now missing.

Mehrauli Inscription / Garuda Pillar – Background

- The Mehrauli Iron Pillar was originally located on a hill near the Beas River and was transported to Delhi by a Delhi king.

- This pillar attributes the victory of the Vanga Countries to Chandragupta, who fought alone against a confederacy of opponents gathered against him.

- It also praises him for defeating the Vakatkas in a battle that spanned Sindhu’s seven mouths.

- The Mahrauli Iron Pillar is a historical landmark that entices visitors with its intriguing iron structure that has not corroded since its creation over 1600 years ago.

- Despite being exposed to the elements, the Iron Pillar remains robust, serving as a great illustration of ancient India’s scientific and engineering progress.

- Archaeologists and materials scientists are still working to answer one of the world’s oldest riddles.

- Iron Pillar, which rises magnificently at a height of 24 feet, is located within the Qutub Complex, which also houses the famed Qutub Minar. It is located in the Qutb Complex, in front of the Quwwatul Mosque.

- It contains verses composed in the Sanskrit language, in shardulvikridita metre.

Iron Pillar

Mahrauli Inscription / Garuda Pillar – History

- According to academics, the Mehrauli Iron Pillar was built during the early Gupta dynasty (320-495 AD). This conclusion is based on the workmanship style and inscription on the pillar, as well as the language.

- Scholars have discovered the name “Chandra” in the third stanza of the inscription on the Iron pillar, which signifies kings of the Gupta Dynasty.

- The king is identified as Chandragupta II (375-415 CE) who was the son of King Samudragupta.

- Chandragupta-II of the Gupta dynasty named this pillar Vishnupada in honor of Lord Vishnu.

- According to one popular theory, the Iron Pillar was erected on top of a hill in Madhya Pradesh called Udaygiri, from which King Iltutmish (1210-36 AD) carried it to Delhi following his triumph.

- According to some experts, King Anangpal II, Tomar King, lifted the Delhi Iron Pillar and installed it in the main shrine at Lal Kot in New Delhi around 1050 AD.

- When King Prithviraj Chauhan, Anangpal’s grandson, was defeated by the Muhammad Ghori army in 1191, Qutb-ud-din Aibak erected the Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque at Lal Kot.

- The pillar was then relocated from its original site in front of the mosque to its current location.

Features

Mehrauli Inscription / Garuda Pillar – Features

- Mehrauli’s Iron Pillar stands at a height of 7.2 metres. It rests on a 48-centimetre-diameter intricately carved foundation that weighs 6.5 tonnes.

- The pillar’s summit is embellished with carvings. It also includes a deep hole that is claimed to be the foundation where Hindu Lord Garuda‘s statue was placed. Inscriptions are engraved onto an iron pillar.

- The most intriguing aspect of Iron pillar architecture is that it has not rusted in over 1600 years of exposure to the elements.

- Some of the inscriptions on the iron pillars hint to its origin. However, the original place where it was created is still being investigated.

- At roughly 400 cm from the present ground level of the pillar, there is a conspicuous depression in the centre of the otherwise smooth Iron Pillar.

- It is reported that the devastation was caused by the close-range fire of cannonballs.

Mehrauli Inscription

Conclusion

The Mehrauli iron pillar, also known as the Delhi iron pillar or Lohe ki Lat, is located within the Qutb complex. It was constructed in the fourth or fifth centuries CE and moved to this position 800 years later during the Delhi Sultanate period. The Pillar is remarkable for its rusty state, despite being made of 99% iron and having been built in the 5th century CE, giving it a lifespan of roughly 1600 years. It is thought to have featured the insignia of the mythological bird Garuda, the Guptas’ symbol, at the top, but it is now lost.

Q19. What is the political importance of Besanagar Garud Pillar inscription? Discuss.

- Garuda pillar is in vidisha(besnagar) in madhya pradesh. It is near to the sanchi stupa.

- Heliodorous dedicated this pillar to god vasudeva. He was the greek ambassador of greek king antialkidas in the court of the king bhagabhadra. Heliodorous describes himself as bhagavata.

- According to the pillar’s information, heliodorus was converted to vaishnavism.

- The pillar symbolizes the joining of earth, space and heaven. This pillar is neither tapered nor polished as in ashokan pillars.

- The 1st inscription on it describes the private religion of heliodorus.

- The second inscription was a verse from mahabharat.

- The pillar consists of a shaft, a base and a capital and is also carved with bell shaped and flowers on it.

Q20. Rummindeipillar Inscription.

Lumbini Pillar Edict in Nepal is known as the Rummindei Pillar Inscription .The Lumbini Pillar Edict recorded that sometime after the twentieth year of his reign, Ashoka travelled to the Buddha’s birthplace and personally made offerings. He then had a stone pillar set up and reduced the taxes of the people in that area.

Ashoka’s pillars are a series of columns spread across the Indian subcontinent, erected or at least engraved by edicts during his rule from c. BC 268 to 232. “pillars of the Dharma”pillars of the Dharma. These pillars are significant landmarks to India’s architecture, most of which show the characteristic Mauryan polish. Twenty of the pillars erected by Ashoka, including those with inscriptions from his edicts, still survive. Out of which seven complete specimens are known, only a few with animal capitals remain. Firuz Shah Tughlaq moved two pillars to Delhi. Later, several pillars were moved by Mughal Empire founders, removing the animal capitals. The pillars were pulled, often hundreds of miles, to where they were erected, averaging between 12 and 15 m in height, and weighing up to 50 tons each. All the foundations of Ashoka were founded in Buddhist monasteries, several important Buddha-life sites, and pilgrimage sites. There are inscriptions addressed to monks and nuns on some of the columns. Some were erected to celebrate Ashoka’s visit. The Pillar marks the astonishing occurrence of the birth of Buddha. With legal markings and texts on it that can be read, the Pillar is well maintained.

Q21. Write an essay on Sarnath Buddha Image Inscription of Kanishka I.

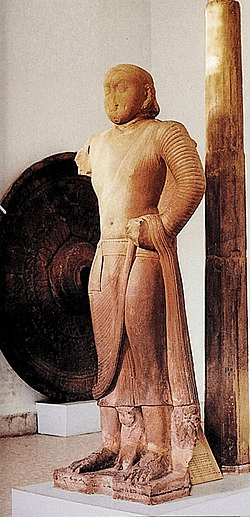

The Bala Bodhisattva is an ancient Indian statue of a Bodhisattva, found in 1904-1905 by German archaeologist F.O. Oertel (1862-1942) in Sarnath, India. The statue has been decisive in matching the reign of Kanishka with contemporary sculptural style, especially the type of similar sculptures from Mathura, as its bears a dated inscription in his name. This statue is in all probability a product of the art of Mathura, which was then transported to the Ganges region.

The inscription on the Bodhisattva explains that it was dedicated by a “Brother” (Bhikshu) named Bala, in the “Year 3 of Kanishka”. This allows to be a rather precise date on the sculptural style represented by the statue, as year 3 is thought to be approximately 123 CE.

The inscription further states that Kanishka (who ruled from his capital in Mathura) had several satraps under his commands in order to rule his vast territory: the names of the Indo-Scythian Northern Satraps Mahakshatrapa (“Great Satrap”) Kharapallana and the Kshatrapa (“Satrap”) Vanaspara are mentioned as satraps for the eastern territories of Kanishka’s empire.

The Bala Bodhisattva with shaft and chatra umbrella, dedicated in “the year 3 of Kanishka” (circa 123 CE) by “brother (Bhikshu) Bala”. The right arm would have been raised in a salutation gesture. Sarnath Museum.

Main inscription

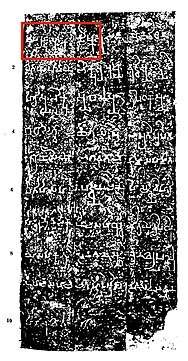

Complete inscription of Bhikshu Bala on the octagonal shaft of the umbrella, with the phrase

Mahārājasya Kāṇiṣkasya “Of The Great King Kanishka” at the beginning.

Inscription on the octagonal shaft

There are altogether three inscriptions, the largest one being the inscription on the octagonal shaft of the umbrella. The octagonal shaft and its umbrella are visible in “Avatāraṇa: a Note on the Bodhisattva Image Dated in the Third Year of Kaniṣka in the Sārnāth Museum” by Giovanni Verardi.[6]

Original text:

1. mahārajasya kaṇiskasya sam 3 he 3 di 20-2

2. etaye purvaye bhiksusya pusyavuddhisya saddhyevi-

3. harisya bhiksusya balasya tr[e]pi[ta]kasya

4. bodhisatvo chatrayasti ca pratisthapit[o]

5. baranasiye bhagavato ca[m]k[r?]ame saha mata-

6. pitihi saha upaddhyayaca[rye]hi saddhyevihari-

7. hi amtevasikehi ca saha buddhamitraye trepitika-

8. ye saha ksatra[pe]na vanasparena kharapall[a]-

9. nena ca saha ca[tu]hi parisahi sarvasatvanarn

10. hita[szc]sukharttham

Translation:

1. In the year 3 of the Great King Kaniska, [month] 3 of winter, day 22:

2–3. on this aforementioned [date], [as the gift] of the Monk Bala, Tripitaka Master and companion of the Monk Pusyavuddhi [= Pusyavrddhi or Pusyabuddhi?],

4. this Bodhisattva and umbrella-and-staff was established

5. in Varanasi, at the Lord’s promenade, together with [Bala’s] mother

6. and father, with his teachers and masters, his companions

7. and students, with the Tripitaka Master Buddhamitra,

8. with the Ksatrapa Vanaspara and Kharapallana,

9. and with the four communities,

10. for the welfare and happiness of all beings.

Q22. What is the language and script of ‘Rummindei inscription’?

Edicts inscribed at the beginning of Ashoka’s reign; in Prakrit, Greek and Aramaic. Minor Pillar Edicts: Schism Edict, Queen’s Edict, Rummindei Edict, Nigali Sagar Edict; in Prakrit.

Q23. What do you understand by ‘Kshatrayasti’?

Kshatriya, also spelled Kshattriya or Ksatriya, second highest in ritual status of the four varnas, or social classes, of Hindu India, traditionally the military or ruling class.

In the second place were the rulers, also known as kshatriyas. They were expected to fight battles and protect people. Third were the vish or the vaishyas. They were expected to be farmers, herders, and traders.

Q24. What do you mean by Piyadasin?

Priyadasi, also Piyadasi or Priyadarshi, was the name of a ruler in ancient India, or simply an honorific epithet which means “He who regards others with kindness”, “Humane”, “He would glances amiably”.

The title “Priyadasi” appears repeatedly in the ancient inscriptions known as the Major Rock Edicts or the Major Pillar Edicts, where it is generally used in conjunction with the title “Devanampriya“ (“Beloved of the Gods”) in the formula “Devanampriya Priyadasi”. Some of the inscriptions rather use the title “Rajan Priyadasi” (“King Priyadarsi”). It also appears in Greek in the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription (c. 260 BCE), when naming the author of the proclamation as βασι[λ]εὺς Πιοδασσης (“Basileus Piodassēs”), and in Aramaic in the same inscription as “our lord, king Priyadasin”

According to Christopher Beckwith, “Priyadasi” could simply be the proper name of an early Indian king, author of the Major Rock Edicts or the Major Pillar Edicts inscriptions, whom he identifies as probably the son of Chandragupta Maurya, otherwise known in Greek source as Amitocrates.

Q25. What is the date of Saka Samvat?

The Shaka era is a historical Hindu calendar era (year numbering), the epoch (its year zero) of which corresponds to Julian year 78.

The era has been widely used in different regions of India as well as in SE Asia.

There are two Shaka era systems in scholarly use, one is called Old Shaka Era, whose epoch is uncertain, probably sometime in the 1st millennium BCE because ancient Buddhist and Jaina inscriptions and texts use it, but this is a subject of dispute among scholars. The other is called Saka Era of 78 CE, or simply Saka Era, a system that is common in epigraphic evidence from southern India. A parallel northern India system is the Vikrama Era, which is used by the Vikrami calendar linked to Vikramaditya.

Q26. Why Sarnath is famous for?

Sarnath is a place located 10 kilometres north-east of Varanasi near the confluence of the Ganges and the Varuna rivers in Uttar Pradesh, India. The deer park inSarnath is where Gautama Buddha first taught the Dhamma, and where the Buddhist Sangha came into existence through the enlightenment of Kondanna.

Q27. Who was Ravikirti?

Ravikriti was the court poet of Pulakesin II, the Chalukya King.

Q28. Where ‘Kahaum’ is situated?

Kahaum pillar is an 8 m (26 ft 3 in) structure located in Khukhundoo in the state of Uttar Pradesh, and dates to the reign of Gupta Empire ruler Skandagupta. The 5th century an 8 metres (26 ft) pillar known as Kahaum pillar was erected during the reign of Skandagupta.