Q1. Differentiate Confederation with that of Federation.

Confederation and Federation are both forms of government that involve the association of different states or regions, but they differ in significant ways.

A Confederation is a political system in which a group of independent states or regions come together and agree to delegate some of their powers to a central government, while retaining their sovereignty and independence. The central government is usually limited in its powers and can only act on behalf of the member states when authorized to do so. Examples of Confederations include the European Union and the Confederacy of Independent States (CIS).

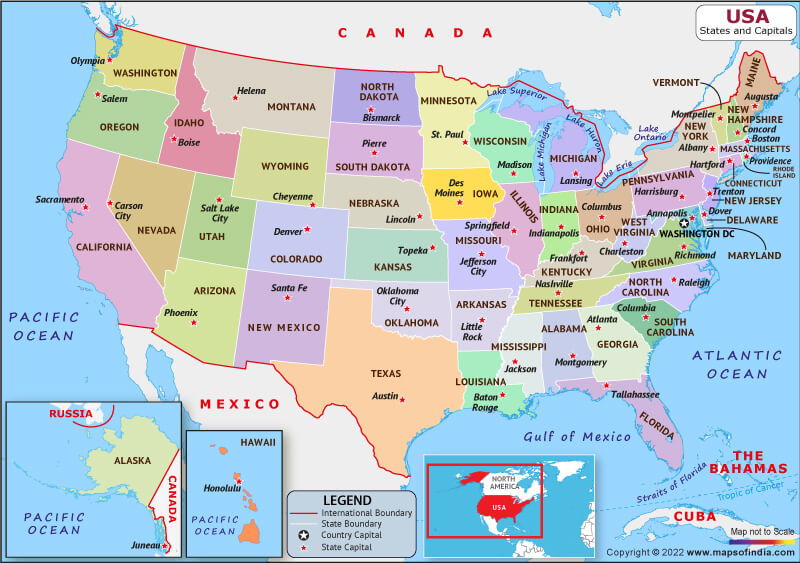

On the other hand, a Federation is a political system in which a central government shares powers with constituent states or regions. The central government has authority over certain matters such as foreign policy, national defense, and currency, while the constituent states retain their powers over other matters such as education, healthcare, and local laws. Examples of Federations include the United States, Canada, and Australia.

In summary, a Confederation involves the delegation of some powers from the member states to the central government, while a Federation involves the sharing of powers between the central government and the constituent states.

Q2. Who has written the book “The spirit of Laws”?

The book “The Spirit of Laws” was written by the French political philosopher Baron de Montesquieu. It was first published anonymously in 1748 and quickly became a widely influential work in political theory. In “The Spirit of Laws,” Montesquieu proposes the idea of the separation of powers, which became a fundamental principle in modern constitutional theory. The book also explores various forms of government, the relationship between climate and politics, and the role of laws and institutions in maintaining a stable society.

Q3. Make distinction between Constitution and Constitutionalism.

Constitution and constitutionalism are related concepts, but they have distinct meanings.

A Constitution is a written document that outlines the fundamental principles, institutions, and procedures of a government. It establishes the structure of the government, defines the powers of its different branches, and sets out the rights and freedoms of the people. A Constitution is usually considered the supreme law of a country, and all other laws and policies must be consistent with its provisions.

Constitutionalism, on the other hand, is the belief in the importance of having a government that operates within the bounds of a constitution. It is a political and legal philosophy that emphasizes the principles of limited government, the rule of law, and the protection of individual rights and freedoms. Constitutionalism holds that the powers of government should be constrained by a constitution, and that the people should have a voice in shaping and amending that constitution.

In summary, a Constitution is a written document that sets out the rules and structure of a government, while constitutionalism is the idea that governments should be constrained by a constitution and that individual rights and freedoms should be protected.

Examples of Constitutions include:

- The United States Constitution, which was written in 1787 and is the supreme law of the United States.

- The Constitution of India, which was adopted in 1950 and outlines the framework for the Indian government.

- The Constitution of South Africa, which was adopted in 1996 and is known for its emphasis on protecting human rights and promoting equality.

Examples of Constitutionalism include:

- The Magna Carta, which was signed in 1215 and is considered a foundational document in the development of constitutionalism. It limited the power of the English monarch and established the principle that everyone, including the king, was subject to the law.

- The American Revolution and the subsequent creation of the United States Constitution, which were driven in part by the belief in the importance of limited government and the protection of individual rights.

- The adoption of constitutional reforms in many countries around the world over the past several decades, as part of a broader movement towards democratization and the protection of human rights.

Q4. Who is said to have made the first comparative study of governments?

Aristotle (c. 384 BCE–c. 322 BCE) has sometimes been credited with being the “father” of political science, and attributed with being one of the first to use comparative methodologies for analyzing competing Greek city-states.

Q5. What do you mean by ‘Rule of Law’?

Origin

-

- Concept of Rule of Law originated with Chief Justice Edward Coke of England, emphasizing that the King is subject to law.

- Developed further by A.V. Dicey in his 1885 work “The Law and the Constitution”.

History Of Rule Of Law

- The rule of law has a long history. Around 350 BC, Greek philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle addressed the notion of the rule of law.

- Sir Edward Coke, the Chief Justice during James I’s reign, invented the notion of the rule of law.

- The rule of law in England originated in approximately 1215 when King John of England signed the Magna Carta.

- The signing of the Magna Carta represented the Monarchy of England’s permission to be subject to the law and for the law to be supreme.

- Prof. Albert Venn Dicey evaluated the concept of the Rule of Law, and as per his theory rule of law is based on various principles.

Meaning and Scope

-

- Supremacy of Law: Law has absolute dominance, excluding arbitrary government actions.

- No individual can be punished except by due process of law.

- Equality before Law: All individuals, regardless of class, are subject to the same law administered by ordinary courts.

- Exemption of civil servants from ordinary courts violates this principle.

- Judge-made Constitution: In England, fundamental rights are results of judicial decisions rather than a written constitution.

- Supremacy of Law: Law has absolute dominance, excluding arbitrary government actions.

Rule of Law in the Indian Constitution

-

- The Preamble of the Constitution emphasizes Justice, Liberty, and Equality.

- These concepts are enforceable through Part III (Fundamental Rights).

- The Judiciary, Legislature, and Executive are bound by the Constitution.

- Judicial review allows courts to enforce fundamental rights and quash illegal executive actions.

- In Chief Settlement Commissioner Punjab v. Om Prakash, the Supreme Court highlighted the authority of law courts to test the legality of administrative actions.

Exceptions to the Rule of Law

-

- Private citizens vs. public officials: Public officials (e.g. police) have certain powers not available to private citizens.

- Special rules for certain classes: Armed forces and professionals (e.g. lawyers, doctors) follow specific regulations.

- Discretionary powers: Ministers and executive bodies have discretionary powers under statutes.

Conclusion

-

- The Constitution of India ensures the Rule of Law by protecting rights, promoting equality, and checking arbitrariness.

- Challenges like outdated laws and overcrowded courts are being addressed by bodies like the Law Commission of India to ensure the effective operation of the Rule of Law.

Q6. Describe two features of Rule of Law.

Key Features of Rule of Law

Legal Certainty and Transparency

Legal certainty is a cornerstone of the rule of law. It means that laws must be clear, accessible, and predictable, so individuals can understand their rights and obligations. Transparency in the legislative process ensures that laws are made openly and that citizens are informed about the laws that govern them. This feature helps prevent arbitrary governance and allows individuals to plan their actions with confidence that the law will be applied consistently.

Equality Before the Law

Equality before the law is a fundamental aspect of the rule of law. This principle asserts that all individuals, regardless of status, wealth, or power, are subject to the same laws and are entitled to equal protection under the law. It ensures that no one is above the law and that everyone has the same legal rights and obligations. This equality promotes fairness and justice within the legal system.

Accountability to the Law

Accountability to the law means that government officials and public servants are bound by the law and must act within the limits set by the law. It requires that any abuse of power or unlawful actions by authorities be subject to legal scrutiny and sanctions. This accountability ensures that those in positions of power are held responsible for their actions, maintaining the integrity of the legal system and preventing tyranny.

Independence of the Judiciary

An independent judiciary is essential for the rule of law. Judges must be free from external pressures and influence, whether from the government, private interests, or public opinion. Judicial independence ensures that courts can make impartial decisions based solely on the law and facts of each case. This independence is critical for maintaining public trust in the legal system and for safeguarding individual rights and freedoms.

Access to Justice

Access to justice is a vital component of the rule of law. It ensures that all individuals have the ability to seek and obtain legal remedies and to have their cases heard by a competent and impartial tribunal. This includes access to legal representation, fair trial procedures, and the ability to challenge the legality of government actions. Ensuring access to justice helps uphold the rights of individuals and promotes confidence in the legal system.

Fairness and Due Process

Fairness and due process are integral to the rule of law. These principles require that legal processes be conducted in a fair and impartial manner, with respect for the rights of all parties involved. Due process includes the right to a fair hearing, the presumption of innocence, and the right to appeal. Ensuring fairness and due process protects individuals from arbitrary and unjust treatment by the legal system.

Protection of Fundamental Rights

The rule of law includes the protection of fundamental human rights and freedoms. Legal frameworks must safeguard rights such as freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and the right to privacy. Protecting these rights is essential for maintaining a just and equitable society where individuals can live without fear of oppression or discrimination.

Separation of Powers

The separation of powers is a key feature of the rule of law, dividing government authority among the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. This division creates a system of checks and balances, ensuring that no single branch has absolute power. The separation of powers prevents the concentration of power and provides mechanisms for accountability and oversight, promoting the rule of law and protecting individual liberties.

Legal Remedies and Redress

The rule of law guarantees that individuals have access to legal remedies and redress for violations of their rights. This means that courts and other legal institutions must be empowered to provide effective solutions to legal grievances. The availability of legal remedies ensures that wrongs can be righted and that justice is served, reinforcing the rule of law.

In summary, the rule of law encompasses principles such as legal certainty and transparency, equality before the law, accountability, judicial independence, access to justice, fairness and due process, protection of fundamental rights, separation of powers, and the availability of legal remedies. These features collectively ensure that the legal system operates fairly, impartially, and justly, upholding the rights and freedoms of individuals and maintaining the integrity of the democratic process.

Q7. Who has written the book ‘New aspects of Politics’?

IN 1925, Charles E. Merriam wrote the book new aspects of politics in which he criticized the contemporary political science for its lack of scientific rigour and deprecated the work of historians as they had ignored the role of psychological, sociological and economic factors in human affairs.

Q8. Who has given the theory of ‘Separation of Powers’?

The theory of Separation of Powers was first introduced by the French political philosopher Baron de Montesquieu in his book “The Spirit of the Laws” (1748). Montesquieu argued that the best way to prevent tyranny and abuse of power by the government is to divide its functions and responsibilities among different branches or organs of the state. He proposed that the state should be divided into three separate branches: the legislative, the executive, and the judicial.

Montesquieu’s theory of Separation of Powers has since been adopted by many democratic countries and enshrined in their constitutions as a fundamental principle. In the United States, for example, the Separation of Powers is a cornerstone of the Constitution, with the legislative branch (Congress), executive branch (the President), and the judicial branch (the Supreme Court) all given distinct and separate powers and responsibilities.

Q9. What do you understand by political system?

In political science, a political system means the form of political organization that can be observed, recognised or otherwise declared by a society or state.

It defines the process for making official government decisions. It usually comprizes the governmental legal and economic system, social and cultural system, and other state and government specific systems. However, this is a very simplified view of a much more complex system of categories involving the questions of who should have authority and what the government influence on its people and economy should be.

Along with a basic sociological and socio-anthropological classification, political systems can be classified on a social-cultural axis relative to the liberal values prevalent in the Western world, where the spectrum is represented as a continuum between political systems recognized as democracies, totalitarian regimes and, sitting between these two, authoritarian regimes, with a variety of hybrid regimes; and monarchies may be also included as a standalone entity or as a hybrid system of the main three.

Definition

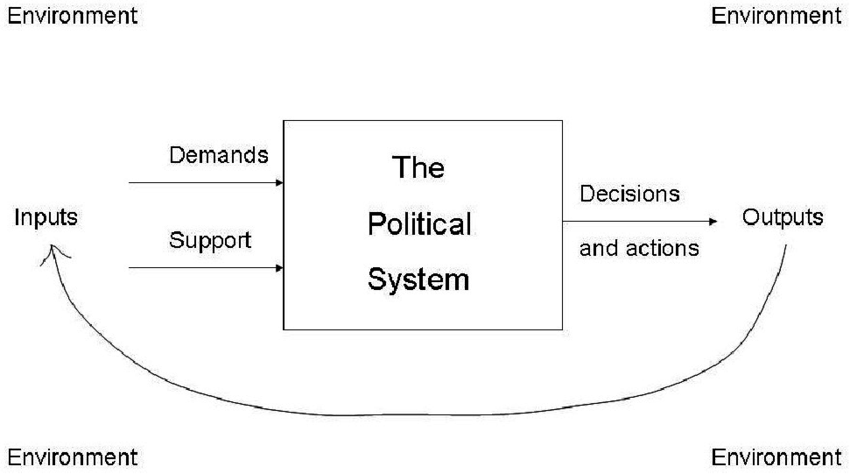

According to David Easton, “A political system can be designated as the interactions through which values are authoritatively allocated for a society”. Political system refers broadly to the process by which laws are made and public resources allocated in a society, and to the relationships among those involved in making these decisions.

Q10. What is difference between traditional approach and modern approach in comparative politics.

Comparative politics is a subfield of political science that focuses on the study of different political systems, their institutions, and their interactions. Over time, there have been significant changes in the way scholars approach comparative politics, with traditional approaches giving way to modern approaches.

- Theoretical focus

Traditional approaches to comparative politics tend to focus on formal political institutions, such as constitutions, laws, and formal decision-making processes. This approach is grounded in a positivist framework, which emphasizes empirical research and the use of quantitative methods to study large datasets and test hypotheses. Traditional approaches assume that political institutions are the primary determinants of political outcomes and that their design and function are crucial to understanding political systems.

Modern approaches, on the other hand, take a broader perspective and consider a wider range of factors that shape politics, such as social movements, cultural norms, and informal power structures. Modern approaches draw on a range of theoretical frameworks, including post-positivist, critical, and interpretive approaches, which emphasize the importance of context, meaning, and power in shaping political outcomes.

- Methodology

Traditional approaches to comparative politics rely heavily on quantitative research methods, such as statistical analysis, to study large datasets and test hypotheses. This approach is based on the assumption that social phenomena can be measured and studied using objective methods, and that empirical data can be used to generate theories about political systems.

Modern approaches, by contrast, place a greater emphasis on qualitative research methods, such as case studies and ethnography, to gain a deeper understanding of political phenomena and the experiences of people affected by political processes. Modern approaches recognize that political phenomena are often complex and multifaceted, and that quantitative methods may not capture the nuances of political interactions and the experiences of individuals and communities.

- Scope of analysis

Traditional approaches to comparative politics tend to focus on the formal structures of government and their role in shaping political outcomes. This approach tends to ignore informal power structures, such as patronage networks and social norms, which can have a significant impact on political behavior and outcomes.

Modern approaches, by contrast, take a broader perspective and consider a wider range of factors that shape politics, such as social movements, cultural norms, and informal power structures. Modern approaches recognize that political phenomena are often complex and multifaceted, and that understanding these phenomena requires an analysis of the social, cultural, and historical context in which they occur.

- Power and agency

Traditional approaches to comparative politics tend to view power as concentrated in formal political institutions, such as the state, and assume that these institutions are the primary sources of political agency. This approach tends to overlook the role of social movements, civil society, and other non-state actors in shaping political outcomes.

Modern approaches, by contrast, recognize that power is diffuse and that political agency is distributed across a range of actors and institutions, including non-state actors such as civil society organizations and social movements. Modern approaches also recognize that power is not simply exercised by elites but is also contested and negotiated by ordinary people in their daily lives.

- Epistemology

Traditional approaches to comparative politics are grounded in a positivist epistemology, which assumes that objective knowledge can be generated through the use of scientific methods and that this knowledge can be used to inform policy decisions. This approach tends to prioritize empirical data over other forms of knowledge and assumes that knowledge is value-free and apolitical.

Modern approaches, by contrast, challenge the assumptions of positivism and adopt a more critical approach to knowledge production. Modern approaches recognize that all knowledge is situated within particular social, cultural, and historical contexts and that knowledge is shaped by power relations. Modern approaches also recognize that the production of knowledge is inherently political and that the ways in which knowledge is produced and disseminated can have important political implications.

- Normative orientation

Traditional approaches to comparative politics tend to be relatively value-neutral and aim to generate objective knowledge about political systems. This approach tends to prioritize empirical research and the use of scientific methods to study political phenomena.

Modern approaches, by contrast, are often more explicitly normative in their orientation and seek to promote social justice and equality. Modern approaches recognize that political systems are embedded in broader social and economic structures, and that the study of politics must be connected to broader debates about social justice and equity.

In summary, the differences between traditional and modern approaches to comparative politics can be seen in their theoretical focus, methodology, scope of analysis, understanding of power and agency, epistemology, and normative orientation. While traditional approaches tend to prioritize empirical research and quantitative methods, modern approaches take a more critical and contextual approach and consider a wider range of factors that shape political outcomes. Modern approaches also recognize that political systems are embedded in broader social and economic structures and that the study of politics must be connected to broader debates about social justice and equity.

Q11. Who has written the book ‘The Political System’?

David Easton has written the book ‘The Political System‘. It was published in 1953 and is considered a seminal work in the field of political science, particularly in the subfield of political systems theory. The book introduced the concept of the political system as a way to understand the structures, processes, and functions of political systems. Easton argued that the political system was a way to analyze and understand how societies make decisions and allocate resources, and that it was essential to understanding how societies functioned as a whole. The book has had a lasting impact on the study of political science and is still widely read and cited today.

Q12. What is Behaviouralism?

Behaviouralism (or behavioralism) is an approach in political science that emerged in the 1930s in the United States. It represented a sharp break from previous approaches in emphasizing an objective, quantified approach to explain and predict political behaviour. It is associated with the rise of the behavioural sciences, modeled after the natural sciences. Behaviouralism claims it can explain political behaviour from an unbiased, neutral point of view.

Behaviouralists seek to examine the behaviour, actions, and acts of individuals – rather than the characteristics of institutions such as legislatures, executives, and judiciaries – and groups in different social settings and explain this behavior as it relates to the political system.

Origins

From 1942 through the 1970s, behaviouralism gained support. It was probably Dwight Waldo who coined the term for the first time in a book called “Political Science in the United States” which was released in 1956. It was David Easton however who popularized the term. It was the site of discussion between traditionalist and new emerging approaches to political science. The origins of behaviouralism is often attributed to the work of University of Chicago professor Charles Merriam, who in the 1920s and 1930s emphasized the importance of examining political behaviour of individuals and groups rather than only considering how they abide by legal or formal rules.

As a political approach

Prior to the “behaviouralist revolution”, political science being a science at all was disputed. Critics saw the study of politics as being primarily qualitative and normative, and claimed that it lacked a scientific method necessary to be deemed a science. Behaviouralists used strict methodology and empirical research to validate their study as a social science. The behaviouralist approach was innovative because it changed the attitude of the purpose of inquiry. It moved toward research that was supported by verifiable facts. In the period of 1954-63, Gabriel Almond spread behaviouralism to comparative politics by creation of a committee in SSRC. During its rise in popularity in the 1960s and ’70s, behaviouralism challenged the realist and liberal approaches, which the behaviouralists called “traditionalism”, and other studies of political behaviour that was not based on fact.

To understand political behaviour, behaviouralism uses the following methods: sampling, interviewing, scoring and scaling, and statistical analysis.

Behaviouralism studies how individuals behave in group positions realistically rather than how they should behave. For example, a study of the United States Congress might include a consideration of how members of Congress behave in their positions. The subject of interest is how Congress becomes an ‘arena of actions’ and the surrounding formal and informal spheres of power.

Meaning of the term

David Easton was the first to differentiate behaviouralism from behaviourism in the 1950s (behaviourism is the term mostly associated with psychology). In the early 1940s, behaviourism itself was referred to as a behavioural science and later referred to as behaviourism. However, Easton sought to differentiate between the two disciplines:

Behavioralism was not a clearly defined movement for those who were thought to be behavioralists. It was more clearly definable by those who were opposed to it, because they were describing it in terms of the things within the newer trends that they found objectionable. So some would define behavioralism as an attempt to apply the methods of natural sciences to human behavior. Others would define it as an excessive emphasis upon quantification. Others as individualistic reductionism. From the inside, the practitioners were of different minds as what it was that constituted behavioralism. […] And few of us were in agreement.

With this in mind, behaviouralism resisted a single definition. Dwight Waldo emphasized that behaviouralism itself is unclear, calling it “complicated” and “obscure.” Easton agreed, stating, “every man puts his own emphasis and thereby becomes his own behaviouralist” and attempts to completely define behaviouralism are fruitless. From the beginning, behaviouralism was a political, not a scientific concept. Moreover, since behaviouralism is not a research tradition, but a political movement, definitions of behaviouralism follow what behaviouralists wanted. Therefore, most introductions to the subject emphasize value-free research. This is evidenced by Easton’s eight “intellectual foundation stones” of behaviouralism:

- Regularities – The generalization and explanation of regularities.

- Commitment to Verification – The ability to verify ones generalizations.

- Techniques – An experimental attitude toward techniques.

- Quantification – Express results as numbers where possible or meaningful.

- Values – Keeping ethical assessment and empirical explanations distinct.

- Systemization – Considering the importance of theory in research.

- Pure Science – Deferring to pure science rather than applied science.

- Integration – Integrating social sciences and value.

Subsequently, much of the behavioralist approach has been challenged by the emergence of postpositivism in political (particularly international relations) theory.

Objectivity and value-neutrality

According to David Easton, behaviouralism sought to be “analytic, not substantive, general rather than particular, and explanatory rather than ethical.” In this, the theory seeks to evaluate political behaviour without “introducing any ethical evaluations.” Rodger Beehler cites this as “their insistence on distinguishing between facts and values.”

Criticism

The approach has come under fire from both conservatives and radicals for the purported value-neutrality. Conservatives see the distinction between values and facts as a way of undermining the possibility of political philosophy. Neal Riemer believes behaviouralism dismisses “the task of ethical recommendation” because behaviouralists believe “truth or falsity of values (democracy, equality, and freedom, etc.) cannot be established scientifically and are beyond the scope of legitimate inquiry.”

Christian Bay believed behaviouralism was a pseudopolitical science and that it did not represent “genuine” political research. Bay objected to empirical consideration taking precedence over normative and moral examination of politics.

Behaviouralism initially represented a movement away from “naive empiricism”, but as an approach has been criticized for “naive scientism”. Additionally, radical critics believe that the separation of fact from value makes the empirical study of politics impossible.

Crick's critique

British scholar Bernard Crick in The American Science of Politics (1959), attacked the behavioural approach to politics, which was dominant in the United States, but little known in Britain. He identified and rejected six basic premises and in each case argued the traditional approach was superior to behaviouralism:

- research can discover uniformities in human behaviour,

- these uniformities could be confirmed by empirical tests and measurements,

- quantitative data was of the highest quality, and should be analyzed statistically,

- political science should be empirical and predictive, downplaying the philosophical and historical dimensions,

- value-free research was the ideal, and

- social scientists should search for a macro theory covering all the social sciences, as opposed to applied issues of practical reform.

Q13. What do you understand by constitution?

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these principles are written down into a single document or set of legal documents, those documents may be said to embody a written constitution; if they are encompassed in a single comprehensive document, it is said to embody a codified constitution. The Constitution of the United Kingdom is a notable example of an uncodified constitution; it is instead written in numerous fundamental acts of a legislature, court cases, and treaties.

Constitutions concern different levels of organizations, from sovereign countries to companies and unincorporated associations. A treaty that establishes an international organization is also its constitution, in that it would define how that organization is constituted. Within states, a constitution defines the principles upon which the state is based, the procedure in which laws are made and by whom. Some constitutions, especially codified constitutions, also act as limiters of state power, by establishing lines which a state’s rulers cannot cross, such as fundamental rights. Changes to constitutions frequently require consensus or supermajority.

The Constitution of India is the longest written constitution of any country in the world, with 146,385 words in its English-language version, while the Constitution of Monaco is the shortest written constitution with 3,814 words. The Constitution of San Marino might be the world’s oldest active written constitution, since some of its core documents have been in operation since 1600, while the Constitution of the United States is the oldest active codified constitution. The historical life expectancy of a constitution since 1789 is approximately 19 years.

Etymology

The term constitution comes through French from the Latin word constitutio, used for regulations and orders, such as the imperial enactments (constitutiones principis: edicta, mandata, decreta, rescripta). Later, the term was widely used in canon law for an important determination, especially a decree issued by the Pope, now referred to as an apostolic constitution.

William Blackstone used the term for significant and egregious violations of public trust, of a nature and extent that the transgression would justify a revolutionary response. The term as used by Blackstone was not for a legal text, nor did he intend to include the later American concept of judicial review: “for that were to set the judicial power above that of the legislature, which would be subversive of all government”.

Q14. What is philosophical approach?

The philosophical approach in the study of comparative politics involves examining political systems and concepts through a philosophical lens. This approach aims to identify and analyze the underlying philosophical assumptions and values that shape political systems and influence political behavior.

The philosophical approach seeks to answer questions such as: What is the proper role of government? What are the rights and responsibilities of citizens? What is the nature of power? What is the ideal society? How can we achieve justice and equality?

Philosophers have contributed to the study of comparative politics by developing theories and concepts that are still relevant today. For example, political philosopher Aristotle argued that the best political system is one that balances the interests of the ruling elite and the common people, while philosopher John Rawls developed the concept of “justice as fairness” as a way to assess political institutions and policies.

In addition, the philosophical approach to comparative politics recognizes the importance of cultural and historical context in shaping political systems and ideas. It also acknowledges the subjective nature of political beliefs and values, and the need for critical reflection and dialogue in the study of political systems.

Socrates is known as father of philosophy. He has given the ‘theory of knowledge’. According to him, the real knowledge is the knowledge of ideas. And the mode of learning this knowledge is logic. Socrates prescribed dialectics. Why this knowledge is superior? Physical world is a world of change. Hence, there cannot be a permanent knowledge. Whereas the world of idea is a world of permanence. Hence this knowledge is of permanent nature, subject to the condition, it is a product of logical reasoning.

Plato: Plato is called as father of political philosophy. He has suggested that it is not enough to understand the features of existing states, it is more important to understand the ‘idea of state’. The purpose of existence of the state.

When we understand the idea, we can mould the existing states which are bound to be imperfect towards perfection. Thus besides the advantage of getting the foundational or permanent knowledge, philosophy can help in making our lives better. Plato emphasised that the knowledge of philosopher is not just for his betterment but for the betterment of the society. Thus philosophy has a huge utility for making our lives better.

Philosophical approach is the oldest approach present in political science. Political science started as a sub discipline of philosophy. Classical scholars dealt with philosophical issues or normative issues like justice, equality, rights, liberties.

Philosophical approach remained dominant approach till second world war. Major development happened in western Europe. Philosophical approach came under criticism by behavioralists. Behavioralists wanted to make political science ‘pure science’. Hence they rejected the study of normative issues. They advocated the study of facts. Lord Bryce held that “we need facts, facts and facts.”

Philosophical theories were criticised as ‘armchair theories’. They do not constitute verifiable and thus are not reliable source of knowledge. They also are inherently biased and divorced from the reality. However scholars like John Rawls, Leo Strauss, Isaiah Berlin, Dante Germino believe that the philosophical approach is most suitable for the discipline of political science.

Q15. Discuss the nature of Comparative Political Institutions.

Comparative Political Institutions refers to the study of different political systems across various countries, and the institutions that comprise these systems. These institutions include executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government, as well as other institutions such as political parties, interest groups, and civil society organizations.

Nature:

-

Comparative Political Institutions are Multidisciplinary: Comparative political institutions draw upon a range of disciplines, including political science, sociology, history, law, and economics. As such, it is an interdisciplinary field of study that seeks to understand the complex interactions between formal institutions of government and other social and economic factors.

-

Comparative Political Institutions are Context-Specific: Comparative political institutions recognize the importance of context in shaping political institutions. Different political systems are influenced by a range of historical, cultural, economic, and social factors. Therefore, comparative political institutions require an in-depth understanding of the specific context in which political institutions operate.

-

Comparative Political Institutions are Comparative: Comparative political institutions are a comparative field of study. This means that scholars compare political institutions across different countries or regions to identify similarities and differences. By comparing political institutions, scholars aim to identify patterns and trends in political development and to evaluate the effectiveness of different political systems.

-

Comparative Political Institutions are Normative: Comparative political institutions have a normative dimension. Scholars in this field are not only interested in describing political institutions but also evaluating them. Scholars may ask questions such as: What makes a political institution effective? What values should a political institution embody? What are the conditions necessary for a democratic system to function effectively?

-

Comparative Political Institutions are Dynamic: Comparative political institutions recognize that political institutions are dynamic and subject to change over time. Changes in social, economic, and political conditions can lead to changes in political institutions. As such, scholars in this field study how political institutions adapt to changing circumstances and the factors that drive institutional change.

-

Comparative Political Institutions are Quantitative: Comparative political institutions employ quantitative methods of analysis to identify patterns and trends in political development. Scholars in this field may use statistical methods to compare political systems across different countries or regions. By using quantitative methods, scholars can identify correlations between political institutions and other social and economic factors.

Key Features of Comparative Political Institutions:

-

Cross-country comparisons: The nature of Comparative Political Institutions involves comparing and analyzing political institutions across different countries. This approach allows for a better understanding of how political institutions function in different contexts and how they impact political outcomes.

-

Institutional analysis: Comparative Political Institutions also involves analyzing the different institutions that make up political systems. This includes the formal institutions, such as the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government, as well as informal institutions such as political parties, interest groups, and civil society organizations.

-

Historical and cultural context: The nature of Comparative Political Institutions recognizes the importance of historical and cultural context in shaping political institutions. Political systems are shaped by a variety of factors such as culture, history, and geography, and Comparative Political Institutions seeks to understand the impact of these factors on political institutions and outcomes.

-

Comparative methodology: The nature of Comparative Political Institutions involves using comparative methodology to identify similarities and differences across political systems. This approach allows for the identification of patterns and trends across different countries, which can inform policy decisions and promote cross-country learning.

Approaches to Comparative Political Institutions:

-

Institutional approach: The institutional approach to Comparative Political Institutions focuses on analyzing the formal institutions that make up political systems, such as the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government. Scholars using this approach seek to understand how these institutions function, how they interact with each other, and how they impact political outcomes.

-

Historical approach: The historical approach to Comparative Political Institutions focuses on analyzing the historical context in which political institutions have evolved. Scholars using this approach seek to understand how historical events and processes have shaped political institutions, and how this has impacted political outcomes.

-

Cultural approach: The cultural approach to Comparative Political Institutions focuses on analyzing the cultural context in which political institutions have evolved. Scholars using this approach seek to understand how cultural factors such as language, religion, and values shape political institutions and impact political outcomes.

-

Rational choice approach: The rational choice approach to Comparative Political Institutions focuses on analyzing the decision-making processes of individuals and institutions within political systems. Scholars using this approach seek to understand how individuals and institutions make decisions and how this impacts political outcomes.

Contributions made by prominent scholars:

-

Robert Dahl: Robert Dahl, a prominent political scientist, contributed to the study of Comparative Political Institutions by developing the concept of polyarchy, which refers to a system of governance in which power is dispersed among multiple groups and individuals.

-

Samuel Huntington: Samuel Huntington, another prominent political scientist, contributed to the study of Comparative Political Institutions by developing the concept of political development, which refers to the process by which political systems evolve and become more complex over time.

-

Juan Linz: Juan Linz, a Spanish political scientist, contributed to the study of Comparative Political Institutions by developing the concept of authoritarianism, which refers to a system of governance in which power is concentrated in the hands of a small group of individuals or institutions.

-

Seymour Martin Lipset: Seymour Martin Lipset, an American political scientist, contributed to the study of Comparative Political Institutions by analyzing the impact of culture on political systems. Lipset argued that certain cultural values, such as individualism and trust, are important for the functioning of democratic institutions.

Q16. Discuss the Scope of Comparative Political Institutions.

The scope of comparative political institutions refers to the extent of the areas that are covered when studying the political institutions of different countries. It is a vast field that encompasses various political systems, structures, and functions of institutions in different countries, and how they interact with each other. The following are some of the aspects that are covered under the scope of comparative political institutions:

-

Comparative analysis of government structures: This involves comparing the structures of government in different countries. It includes the executive, legislative, and judiciary branches of government, as well as the levels of government, such as national, regional, and local.

-

Political parties and electoral systems: This involves the study of political parties and electoral systems in different countries. It includes the types of electoral systems used, such as first-past-the-post or proportional representation, as well as the role of political parties in the government and their ideologies.

-

Comparative study of political cultures: This involves studying the political culture and values of different countries. It includes the attitudes and beliefs of citizens towards the government, their participation in political processes, and their expectations from the government.

-

Comparative analysis of public policies: This involves the study of the policies implemented by governments in different countries. It includes the policies related to social welfare, economic development, and foreign affairs.

-

Comparative analysis of constitutional and legal systems: This involves comparing the constitutional and legal systems of different countries. It includes the sources of law, such as common law or civil law, as well as the interpretation and enforcement of laws by the judiciary.

-

Comparative study of international relations: This involves studying the interactions between countries and their foreign policies. It includes the role of international organizations, such as the United Nations and the World Trade Organization, in shaping international relations.

Prominent scholars in comparative politics, such as Gabriel Almond, Robert Dahl, and Arend Lijphart, have contributed significantly to the scope of comparative political institutions. For instance, Gabriel Almond, in his work “Comparative Political Systems,” emphasized the importance of studying the political culture of different countries in understanding their political institutions. Robert Dahl, in his work “Polyarchy,” focused on the study of democratic institutions and their effectiveness in promoting democratic governance. Arend Lijphart, in his work “Patterns of Democracy,” emphasized the comparative analysis of electoral systems and their impact on democracy.

In conclusion, the scope of comparative political institutions is vast and covers a range of topics, including government structures, political parties, electoral systems, political culture, public policies, constitutional and legal systems, and international relations. Understanding the scope of comparative political institutions is essential for gaining insights into the similarities and differences in political systems across countries, and how they influence the functioning of democratic institutions.

Q17. Discuss the main features of Constitutionalism.

Constitutionalism is a fascinating topic that lies at the very heart of societies worldwide, representing a set of principles or established precedents according to which a state or other organization should be governed. It is an intrinsic part of our socio political landscape, shaping the way societies are organized and how individuals interact within them.

What is Constitutionalism?

Constitutionalism is the idea that the government should be limited in its powers and that its authority depends on its observation of these limitations. The focus is not just on the creation of a constitution but on ensuring that the government adheres to the principles and rules outlined within it. Constitutionalism is a crucial tenet that aids in the prevention of arbitrary governance and promotes the rule of law.

The philosophy of constitutionalism is rooted in the belief that the power to govern should not be concentrated in one place. This is often accomplished through a system of checks and balances, with the various arms of the government—legislature, executive, and judiciary—each checking the powers of the others to maintain a balance. Such a system ensures that no single entity has the ability to overpower the others, fostering an environment where rights and liberties are protected and upheld.

Principles of Constitutionalism

As we unravel the complexities of constitutionalism, it is essential to identify and understand its core principles. These principles are the heart of constitutionalism, guiding its function and application in governance. Let’s break down these principles to further explore their depth and significance.

Popular Sovereignty

One of the fundamental principles of constitutionalism is ‘Popular Sovereignty.’ This principle states that the ultimate power resides with the people. It’s the citizens who choose their representatives through democratic processes, highlighting the key role they play in the government.

Independent Judiciary

An ‘Independent Judiciary’ is another pillar of constitutionalism. It signifies that the judiciary should operate independently of the other branches of government. This independence safeguards the rights and liberties of the public, ensuring that laws and regulations align with the constitution, and promotes ‘Police Accountability.’

Separation of Powers

‘Separation of Powers’ is a principle that prevents the concentration of authority in one branch of government. Instead, the power is divided amongst different branches – typically the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. This balance allows each branch to keep the others in check, a central premise of constitutionalism.

Responsible and Accountable Government

Constitutionalism demands a ‘Responsible and Accountable Government.’ Every government official, from the highest-ranking to the lowest, is answerable to the public and the law. This principle fosters transparency and helps in reducing corruption and misuse of power.

Rule of Law

‘Rule of Law’ is a principle stating that everyone, including the government and its officials, is subject to the law. It ensures equal treatment before the law and is instrumental in promoting fairness and justice in society.

Police Accountability

In relation to the rule of law, the principle of ‘Police Accountability’ emphasizes that law enforcement agencies must operate within the law. It means they should be accountable for their actions, thereby preventing misuse of power and maintaining public trust in the system.

Civilian Control of the Military

Finally, ‘Civilian Control of the Military’ is another vital principle of constitutionalism. It implies that elected civilian officials have control over the military, ensuring that it serves the nation’s best interests and maintains peace and order, rather than seizing power unlawfully.

Understanding these principles provides a solid foundation for comprehending the intricate framework of constitutionalism. From popular sovereignty to civilian control of the military, each principle plays a unique role in shaping our societies, establishing checks and balances, and promoting democratic governance.

Features of Constitutionalism

While the specifics of constitutionalism can vary from country to country, there are several key features that are generally consistent:

- A Written Constitution: A codified, written constitution is often a key feature of a constitutional state. This document outlines the principles and rules that the government must follow.

- Separation of Powers: As previously mentioned, the principle of separating powers between different branches of government is central to constitutionalism.

- Rule of Law: Constitutionalism upholds the idea that every citizen, including government officials, is subject to the law.

- Protection of Rights: The constitution often includes a bill or charter of rights that outlines the fundamental rights and freedoms of citizens.

- Judicial Review: This is the process by which courts can review the actions of the government to ensure they are constitutional.

- Regular Elections: Regular elections are a fundamental feature, ensuring that the government remains representative and accountable to the people.

Significance of Constitutionalism

The significance of constitutionalism is manifold and includes the following aspects:

- Protection of Rights and Liberties: Constitutionalism provides a protective framework for individual and collective rights. This includes the right to freedom of speech, religion, and assembly, among others. By setting clear boundaries for the government, it ensures these rights are not violated.

- Maintaining Order and Stability: Through clear rules and procedures, constitutionalism contributes to political stability by providing an agreed-upon roadmap for governance. This helps to prevent conflicts and power struggles that could destabilize the state.

- Promotion of Democracy: Constitutionalism and democracy often go hand-in-hand. By ensuring that governmental power is not absolute, constitutionalism creates an environment where democratic practices can thrive.

- Encouraging Accountability: Constitutionalism fosters a culture of accountability. Public officials are bound by the constitution and are answerable to the people, reducing the likelihood of corruption and misuse of power.

Constitutionalism and Constitution of India

To further our exploration of constitutionalism, we must illuminate its relationship with a crucial artifact of governance: the constitution. Constitutionalism and constitution, while closely tied, are distinct concepts, each playing a vital role in the political, legal, and social framework of a country.

A constitution is a tangible document, a rulebook if you will, that sets the fundamental political principles, establishes the structure, procedures, powers, and duties of the government, and guarantees certain rights to the people in a written form. It forms the backbone of a country’s legal and political system, providing a blueprint for governance.

On the other hand, constitutionalism is an overarching philosophy, an abstract concept that underpins the operation of the constitution. It goes beyond the text of the constitution to embody a culture of adhering to the rule of law, respect for fundamental rights, and the limiting of government power. It serves as the moral and ethical compass that guides the application and interpretation of the constitution.

Imagine the constitution as the skeleton of a body, providing structure and support. In this analogy, constitutionalism would be the spirit that brings the body to life. It’s the philosophy that breathes meaning and purpose into the structure, ensuring that the constitution is more than just words on paper.

This relationship between the constitution and constitutionalism is symbiotic. While the constitution provides the framework for governance, constitutionalism ensures that this framework is applied justly and fairly. The constitution sets the rules, while constitutionalism instills a culture of following these rules. Hence, the constitution and constitutionalism, together, form the cornerstone of a democratic society.

In essence, while the constitution is the concrete embodiment of the principles of governance, constitutionalism is the belief system that ensures those principles are upheld. It is the driving force that ensures the spirit of the constitution is respected, its norms are internalized, and its limitations are observed.

Therefore, understanding the nuanced relationship between constitutionalism and the constitution is instrumental in grasping the complexities of governance and law. Each informs and shapes the other, intertwining to form the bedrock upon which societies are built and governed.

Q18. Explain the concept of Separation of Powers.

Introduction

The separation of powers is imitable for the administration of federative and democratic states. Under this rule the state is divided into three different branches- legislative, executive and judiciary each having different independent power and responsibility on them so that one branch may not interfere with the working of the others two branches. Basically, it is the rule which every state government should follow in order to enact, implement the law, apply to specific case appropriately. If this principle is not followed then there will be more chances of misuse of power and corruption If this doctrine is followed then there will be less chance of enacting a tyrannical law as they will know that it will be checked by another branch. It aims at the strict demarcation of power and tries to bring the exclusiveness in the functioning of each organ.

In India, functions are separated from powers rather than the other way around. The idea of the separation of powers is not properly followed in India, unlike in the US. The court has the authority to overturn any unlawful legislation that the legislature passes thanks to a system of checks and balances that has been put in place.

Because it is unworkable, the majority of constitutional systems today do not have a tight division of powers among the several organs in the traditional sense. Although the theory of separation of powers is not expressly recognised in the Constitution in its absolute form, the Constitution does provide provisions for a fair division of duties and authority among the three branches of government.

Background

The term “separation of powers” or “trias–politica “ was initiated by Charles de Montesquieu. For the first time, it was accepted by Greece and then it was widely used by the Roman Republic as the Constitution of the Roman Republic. Its root is traceable in Aristotle and Plato when this doctrine became a segment of their marvels. In 16th and 17th-century British politicians Locke and Justice Bodin, a French philosopher also expressed their opinion regarding this doctrine. Montesquieu was the first one who articulated this principle scientifically, accurately and systemically n his book “ Esprit des Lois” (The Spirit Of Laws) which was published in the year 1785.

Montesquieu, a French scientist, originally proposed the doctrine of separation of powers in his book “Espirit des Louis” published in 1747. (The spirit of the laws). Montesquieu discovered that when power is concentrated in the hands of a single person or a group of people, a despotic government emerges. To avoid this predicament and to limit the government’s arbitrary nature, he argued that the three organs of the state, the Executive, Legislative, and Judiciary, should have a clear distribution of power.

Montesquieu went on to clarify the idea in his own words:

“When the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person, or in the same body or magistrates, there can be no liberty. Again, there is no liberty if the judicial power is not separated from the legislative and executive powers. Where it joined with the legislative power, the life and liberty of the subject would be exposed to arbitrary control, for the Judge would then be the legislator. Where it joined with the executive power, the Judge might behave with violence and oppression. There would be an end of everything, were the same man or same body, whether of the nobles or of the people, to exercise those three powers, that of enacting laws, that of executing the public resolutions, and of trying the causes of individuals.”

Wade and Phillips provide three definitions of the separation of powers:

- That one branch of government should not carry out the duties of another, such as giving ministers legislative authority;

- That one branch of the government should not exert control over or interfere with another branch’s performance of its duties, such as when the judiciary is separate from the executive branch or when ministers are not answerable to Parliament;

- That the same individuals should not serve in more than one of the three branches of government, such as sitting as Ministers in Parliament.

Three formulations of structural classification of governmental powers are included in the separation of powers theory:

- A single person should not serve in more than one of the government’s three branches. Ministers, for instance, should not be allowed to sit in the House of Commons.

- A government organ should not be allowed to meddle with another government organ.

- The functions of one organ of government should not be performed by another.

Meaning

The definition of separation of power is given by different authors. But in general, the meaning of separation of power can be categorized into three features:

- A person forming a part of one organ should not form part of another organ.

- One organ should not interfere with the functioning of the other organs.

- One organ should not exercise the function belonging to another organ.

The separation of power is based on the concept of triaspolitica. This principle visualizes a tripartite system where the powers are delegated and distributed among three organs outlining their jurisdiction each.

To know more about the separation of powers and its relevance in brief, please refer to the video below:

Three-tier machinery of state government

It is impossible for any of the organs to perform all the functions systematically and appropriately. So for the proper functioning of the powers, the powers are distributed among the legislature, executive and judiciary. Now let’s go into the further details of the functioning of each organ.

Legislative

The main function of the legislature is to enact a law. Enacting a law expresses the will of the State and it also acts as the wain to the autonomy of the State. It is the basis for the functioning of executive and judiciary. It is spotted as the first place among the three organs because until and unless the law is framed the functioning of implementing and applying the law can be exercised. The judiciary act as the advisory body which means that it can give the suggestions to the legislature about the framing of new laws and amendment of certain legislation but cannot function it.

Executive

It is the organs which are responsible for implementing, carrying out or enforcing the will of the state as explicit by the constituent assembly and the legislature. The executive is the administrative head of the government. It is called as the mainspring of the government because if the executive crack-up, the government exhaust as it gets imbalanced. In the limited sense, executive includes head of the minister, advisors, departmental head and his ministers.

Judiciary

It refers to those public officers whose responsibility is to apply the law framed by the legislature to individual cases by taking into consideration the principle of natural justice, fairness.

Significance

As it is a very well known fact that whenever a large power is given in the hand of any administering authority there are higher chances of maladministration, corruption and misuse of power. This doctrine helps prevent the abuse of power. This doctrine protects the individual from the arbitrary rule. The government is the violator and also protects individual liberty.

Summarily, the importance can be encapsulated in the following points:

- Ending the autocracy, it protects the liberty of the individual.

- It not only safeguards the liberty of the individual but also maintains the efficiency of the administration.

- Focus on the requirement of independence of the judiciary

- Prevent the legislature from enacting an arbitrary rule.

Constitutional status of separation of power in India

Going through the provisions of Constitution of India one may be ready to say that it has been accepted in India. Under the Indian Constitution:

| Legislature | Parliament ( Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha)

State legislative bodies |

| Executive | At the central level- President

At the state level- Governor |

| Judiciary | Supreme Court, High Court and all other subordinate courts |

The Parliament is competent enough to make any law subject to the conditions of Constitution and there are no restrictions on its law-making powers. The president power and functions are given in the Constitution itself (Article 62 to Article 72). The judiciary is self –dependent in its field and there is no obstruction with its judicial functions either by Legislature or the Executive. The High Court under Article 226 and Article 227 and Supreme Court under Article 32 and Article 136 of Constitution are given the power of judicial review and any law passed by the legislature can be declared void by the judiciary if it is inconsistent with Fundamental Rights (Article 13). By going through such provisions many jurists are of opinion that doctrine of separation of powers is accepted in India.

Before looking into the case laws, let us understand what the meaning of the doctrine of separation of power is in a strict and broad sense.

The doctrine of separation of power in a rigid sense means that when there is a proper distinction between three organs and their functions and also there should be a system of check and balance.

The doctrine of separation of power in a broad sense means that when there is no proper distinction between three organs and their functions.

In the case of I.C Golakhnath vs State of Punjab, the Constitution brings in actuality the distinct constitutional entities i.e namely, the Union territories, Union and State. It also has three major instruments namely, judiciary, executive and legislature. It demarcates their jurisdiction minutely and expects them to exercise their function without interfering with others functions. They should function within their scope.

If we go through the constitutional provision, we can find that the doctrine of separation of power has not been accepted in a rigid sense in India. There is personnel overlapping along with the functional overlapping. The Supreme Court can declare any law framed by the legislature and executive void if they violate the provisions of the Constitution.

Executive also has an impact on the functioning of the judiciary as they appoint the judges and Chief justice. The list is so exhaustive.

In the case of Indira Gandhi vs Raj Narain, the court held that In our Constitution the doctrine of separation of power has been accepted in a broader sense. Just like in American and Australia Constitution where a rigid sense of separation of power applies is not applicable in India.

Justice Chandrachud also expressed his views by stating:

“The political purpose of the doctrine of separation of power is not widely recognized. No provision can be properly implemented without a check and balance system. This is the principle of restraining which has in its precept, innate in the prudence of self- preservation that discretion is better than its valor.”

In Ram Jawaya vs The State of Punjab, Justice Mukherjee observed:

“In India, this doctrine has been not be accepted in its rigid sense but the functions of all three organs have been differentiated and it can be said that our constitution has not been a deliberate assumption that functions of one organ belong to the another. It can be said through this that this practice is accepted in India but not in a strict sense. There is no provision in Constitution which talks about the separation of powers except Article 50 which talks about the separation of the executive from the judiciary but this doctrine is in practice in India. All three organs interfere with each other functions whenever necessary.”

Although, there is an explicit provision in Constitution just like American Constitution that executive power is vested in President under Article 53(1) and in Governor under Article 154(1) but there is no provision which talks about the vesting of legislative and judiciary power in any organ. We can conclude that there is no rigid separation of power.

At the first instance, it appears that our Constitution is based on this doctrine itself as the judiciary is self-sufficient and there is no interference either by executive or legislature. Court also prohibits the administration of judiciary is not to be discussed in the parliament. Power of judicial review and to declare any law as void is given to the Supreme Court. The judges of Supreme Court is appointed by President in consultation. Chief Minister and judges of the supreme court. The Supreme court make the rules and regulations for the effective conduct of business.

However, Article 50 of the Constitution of India talks about the separation of the executive from the judiciary as being a Directive Principle of State Policy it is not enforceable. Certain privileges, power, immunities are given to the Member of Parliament under Article 105. This provision makes the legislature independent. The executive power is conferred on President and Governor they are being exempted from civil and criminal liabilities.

But, if we read carefully it is clear that doctrine is not accepted in a rigid sense. The executive is a portion of the legislature and the executive is accountable for its conduct to the legislature and also its derive its authority from the legislature. Since India has a parliamentary form of government should a mutual connection and coordination between the legislature and executive. As executive power is vested in the president but in actuality, the real head is Prime Minister of India along with Council of Minister and president is only a nominal head. Article 74(1) talks that executive head has to conduct in conformity with the aid and advice of Cabinet.

Ordinarily, all the legislative power is vested in the legislature but in certain circumstances, the president may be empowered to exercise the legislative power. For example, the president can issue ordinance under Article 123 when the parliament is not in session, making the rules when there is an emergency. Sometimes the president may also exercise judiciary power. When a president is being impeached, both houses take active participation and finalize the charges.

Judiciary also performs the administrative actions while formulating the regulations and giving guidance for the subordinate court as well as perform legislative powers by framing the rules regulating their own procedure

So it is presumed from the provisions of the constitution that India being a parliamentary form of government does not follow the absolute separation there is an amalgamation of the powers where the connections between the different wings are inevitable and it can be drawn from the constitution itself. Every organ performs all types of functions in one or other form subject to the check and balance by other organs. All three organs are interdependent because India has a Parliamentary democracy. This does not mean that it is not accepted in India it has been accepted up to a certain extent.

But when it is expressly provided that one organ shall not perform functions of the other, then it is prohibited. In the Delhi laws case, it was stated that the legislature should exercise all the powers of legislation only in extraordinary circumstances like when parliament is not in session or emergency. We can say that the legislature is created by the Constitution to enact the laws.

In India, there is no separation of power but there is a separation of powers. Hence, in India, the people are not stuck by the principle by its rigidity. For example, the cabinet minister exercises both the executive and administrative functions. Article 74(1) states that it is mandatory for the executive head to comply with the advice of the cabinet ministers. In Ram Jawaya vs the State of Punjab, it was held that the executive is a part of the legislature and is accountable.

If we talk about the amending power of the Parliament under Article 368, it has been subject to the concept of the basic structure held in case of Kesavananda Bharati vs State of Kerala.

In this case, it was held that the Parliament couldn’t amend the provision in such a way that violated the basic structure.

And if it is made in violation of basic structure then such amendment will be declared as unconstitutional null and void.

Going through this case law regarding the Supreme court judgment it can be observed that the basic structure cannot be amended and strict applicability of doctrine can be seen.

Although strict separation of power is not followed in India like the American Constitution, the system of check and balance is followed. However, no organs are to take over the essential functions of other organs which is the part of the basic structure, not even by amending and if it is amended, such amendment will be declared as unconstitutional.

Impact of the doctrine of separation of powers on democracy

The doctrine of separation of powers seeks to protect the centralization of power in one hand; as history has repeatedly demonstrated, centralisation of power in one or a few hands can lead to disastrous outcomes. The application of this principle makes the government liable, accountable, and answerable to its citizens for its actions, thereby aiding in the promotion and protection of human rights. This eliminates one of the most serious weaknesses of other forms of administration, such as monarchy or dictatorship, in which the king is not accountable to his people. When applied, the principle creates a balance of powers inside the government, in which each of the government’s bodies’ functions are kept in check by the others while remaining independent of one another. This assures that the laws are just, fair, and adhere to the natural justice ideal. Furthermore, because it is independent of the other departments, the court can administer equitable justice. Democracy is flawed without Separation of Power.

Global perspective

Separation of power has been accepted and adopted across the globe. The United States has one of the most initially established versions of this doctrine, which finds its origin in its constitution. The theory of separation of powers in various aspects has been included in certain other constitutions around the world. The Australian Constitution favours the devolution of legislative functions to the executive rather than judicial institutions. This idea is also believed to be the foundation of the Sri Lankan Constitution. France is another country where this doctrine has an effect, and this doctrine flows out of the French constitution. The United Kingdom too has a separation of powers concept on an informal note. Some of the prominent countries that have adopted this concept are as follows:

United States

The concept of separation of powers is quite specifically stated in the US Constitution. It gives Congress, which consists of the Senate and the House of Representatives, legislative authority. The President has executive authority, and the Supreme Court and any further Federal Courts that Congress may establish have judicial authority. The Constitution specifically outlines the President’s powers, and he is elected in a separate election for a fixed term of four years. He is tasked by the Constitution with ensuring that the country’s laws are faithfully carried out. The President has the authority to nominate and dismiss the executive officers known as the Cabinet, who are in charge of the major state departments. This is done to maintain the separation between the executive and legislative branches of government. Neither the President nor any of his secretaries may be members of the Congress, and any member of the Congress may join the government only after resigning from his membership. The President is normally irremovable from office, but the Senate has the power to remove him through the process of impeachment if he commits high crimes and misdemeanours such as bribery or treason. The after-effects of the Watergate scandal of 1972 on the President act as a prominent illustration of this. Once nominated, the Supreme Court’s judges are not subject to the authority of either Congress or the President. But they too could be impeached and forced out of their positions.

The Supreme Court’s authority was created in Marbury v. Madison in 1803 when it ruled that the President’s acts and the Acts of the legislature were both in violation of the Constitution. The Supreme Court also found that any significant delegation of legislative authority by Congress to executive agencies was in violation of the Constitution’s tenet of the separation of powers.

United Kingdom

Unlike the United States, the United Kingdom does have a separation of powers concept and it exists in the country more on an informal note. The United Kingdom benefits more from Black Stone’s “mixed government” with checks and balances doctrine. The U.K. Constitution does not have separation of powers as an essential or defining principle. Because there is no formal division of powers in the United Kingdom due to the lack of a written constitution, any Act of Parliament that grants any power in violation of the concept may be deemed unconstitutional. The Parliament continues to have undisputed authority, and as a result, the Crown rules through ministers who are elected by and answerable to the Parliament. The Act of Settlement, 1700, effectively cemented the judiciary’s independence. The Supreme Court operates with its powers separated from those of Parliament. The Constitutional Reforms Act of 2005‘s Section 61 outlines the structure for judicial appointments. Commission responsible for choosing judges for the Supreme Court and the court of appeals. Thus, the Constitutional Reforms Act of 2005 has generally ensured the independence of the court.

The three branches continue to significantly overlap and are not properly divided. Administrative tribunals rather than regular courts handle many issues that emerge during the course of government. However, by preserving key components of “fair judicial procedure“, the impartiality of the tribunals is kept intact. Senior justices have frequently stated that a division of powers is the foundation of the British Constitution. It cannot be emphasised enough how deeply rooted in the separation of powers the British Constitution is while being mostly unwritten. Parliament makes the laws, and the judiciary interprets them.

Australia

The separation of powers in Australia is achieved by the partition of the Australian organs of government into the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. According to this theory, laws are created by the legislative, implemented by the executive branch, and then interpreted by the court. The word and its use in Australia are a result of the Australian Constitution’s language and structure, which draws its inspiration from democratic ideas ingrained in the Westminster system, the idea of a ‘responsible government’, and the American interpretation of the separation of powers.