1. Meaning and Definition

2. Power in IR

3. Types of Power

3.1. 1.Physical Power

3.2. 2.Psychological Power

3.3. 3.Economic Power

3.4. 4. National Power

3.5. 5.Fast power

3.6. Joseph Nye concept of Power

4. Polarity of Power

5. Methods of Exercising Power

6. Dimensions of Power

7. Role and Use of Power

8. NATIONAL POWER

8.1. Elements of National Power

8.2. Conclusion

9. BALANCE OF POWER

9.1. Meaning of BOP

9.2. The Prerequisites for Balance of Power

9.3. Characteristics of Balance of Power

9.4. Methods of Balance of Power

9.5. Balance of Terror

9.6. Criticism of BOP

9.7. Relevance BOP

Hey champs! you’re in the right place. I know how overwhelming exams can feel—books piling up, last-minute panic, and everything seems messy. I’ve been there too, coming from the same college and background as you, so I completely understand how stressful this time can be.

That’s why I joined Examopedia—to help solve the common problems students face and provide content that’s clear, reliable, and easy to understand. Here, you’ll find notes, examples, scholars, and free flashcards which are updated & revised to make your prep smoother and less stressful.

You’re not alone in this journey, and your feedback helps us improve every day at Examopedia.

Forever grateful ♥

Janvi Singhi

Give Your Feedback!!

Topic – Power, National Power, Balance of Power – Notes in IR (Notes)

Subject – Political Science

(International Relations)

Table of Contents

- Power is the core of politics at all levels—local, national, and international—and has shaped human relations since the earliest societies.

- Understanding international politics requires a clear grasp of the concept of power, because relations among states are fundamentally power relations.

- The connection between state and power is extremely close. As Hartmann observed, power “lurks in the background of all relations between sovereign states,” highlighting its omnipresence.

- Inter-state interactions ultimately manifest as power politics, where decisions, alignments, and conflicts reflect varying degrees of power possessed by states.

- Politics itself is seen as the pursuit and exercise of power, meaning that power is both a motivating force and an instrument within political activity.

- In international relations, power is the primary means through which states seek to achieve and protect their national interests, whether security, economic advantage, or global influence.

- Every state strives to attain, maintain, and enhance power, making it both an end in itself and a means to other ends in global politics.

- A state’s global standing is shaped not by its culture, heritage, or intellectual achievements, but by the quantity and quality of power it commands.

- All states possess power, but unequally, since power exists in different forms, degrees, and dimensions—military, economic, demographic, technological, or ideological.

- Because power determines behaviour, choices, conflicts, and alliances, it is impossible to study international relations without placing power at the analytical centre.

- The study of power has been central to social sciences for centuries, beginning with thinkers like Aristotle, Plato, and Machiavelli, yet it remains ambiguous and contested due to competing definitions and interpretations.

- Scholars highlight that understanding power depends on whose power is being discussed. For example, Hannah Arendt argued that power is not an individual property but emerges from collective action and exists only as long as a group acts together.

- In contrast, Robert Dahl used the inclusive term actors to denote individuals, groups, offices, governments, or states, emphasizing that power relations operate among various forms of human aggregates.

- Max Weber offered one of the most influential definitions by describing power as the probability of an actor realizing their will despite resistance. He viewed power as zero-sum and rooted in the resources, capabilities, and attributes of the actor.

- Critics like Martin argued that Weber did not truly define power but merely offered a basis for comparing actors’ attributes, and by grounding his definition in conflict, he ignored the possibility of mutually beneficial power relations.

- As an alternative, Talcott Parsons viewed power not as domination but as a system resource enabling the fulfillment of collective obligations backed by legitimacy and sanctions, shifting the focus from conflict to social integration.

- However, Anthony Giddens criticized Parsons for assuming that power is always legitimate, thereby overlooking that power is often asymmetrical and exercised over others, making hierarchy an inescapable aspect of power relations.

- These debates show that both Weberian and Parsonian views suffer from conceptual difficulties, reinforcing the idea that power is an essentially contested concept, as noted by scholars like Bierstedt and Gallie.

- Terms such as power, influence, and authority are widely used in politics, law, strategy, and everyday life, yet perceptions differ significantly across professions and contexts, adding to conceptual complexity.

- In international relations, power is foundational because it defines the interactions among states, shaping outcomes in a world lacking any central governing authority. Thus, interpretations of power vary across IR theories, especially between realist and non-realist frameworks.

- Traditional thinkers often defined power in terms of ability, sovereignty, and the capacity to compel obedience, interpreting social and political life as the result of power interactions across domains.

- In a system of anarchy, where states recognize no authority above themselves, some propose the need for a global governing structure through international agreement, while others emphasize balance of power or compromise among states as mechanisms for stability.

Meaning and Definition

- Power is seen “as the ability to get another actor to do what it would not otherwise have done (or not to do what it would have done).

- Power, therefore, is a relationship.

- If thought in terms of international relations, then the state’s attempt to influence others, to a great extent, is determined by its own capabilities, goals, policies and actions which is similarly affected by the behaviour of those with which it interacts.

- Power, in the context of world politics, can be seen as:

- A set of attributes or capabilities

- An influence process

- Ability to control resources, behaviour of other states, events, outcomes of interaction (cooperative or conflictual).

- Power has been defined in various ways, such as the alignment of others’ intentions with the dominant actor’s will, a combination of material and immaterial factors that create obedience, or the ability to compel others against their wishes. These definitions highlight elements of command, obedience, imposition, and control.

- Political scientists emphasise that power is often visible through command–obedience relationships, and since political power is a major form of social power, sociologists treat it as central to understanding social structures.

- Max Weber defined power as the ability of an individual or group to realize their will despite resistance, based on their position in social relations, without requiring justification for this ability.

- Robert Dahl viewed power as a relationship between actors, where one actor gets another to do something they would not otherwise do.

- Harold Lasswell linked power to participation in decision-making and interpersonal relations.

- Hans Morgenthau described political power as control over the minds and actions of others, covering everything from physical coercion to subtle psychological influence, echoing the earlier views of Kautilya, who saw power as “possession of strength” derived from knowledge, military might, and valor.

- Scholars distinguish between power as both an attribute of an actor and as a relationship between actors, making it necessary to analyse a state’s measurable attributes to understand its power capacity.

- Schwarzenberger defined power as the capacity to impose one’s will with the backing of effective sanctions, distinguishing it from influence by noting that influence lacks an explicit threat and from force by noting that force involves actual physical application, not just threat.

- Schleicher differentiated power from influence by stating that power relies on rewards, punishments, and threats, whereas influence changes behaviour through persuasion and consent, without threatened sanctions.

- Dahl, defining power operationally, viewed it as the ability to shift the probability of outcomes, meaning A has power over B if A can alter B’s behaviour from what it would naturally be.

- Hartmann explained that power manifests along a spectrum from persuasion, to pressure, to actual force, reflecting its various intensities and methods of application.

- Duchacek summarized power as the capacity to produce intended effects and realise one’s will.

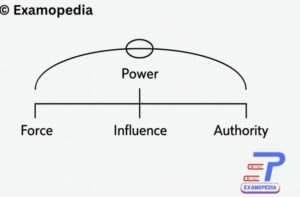

- Couloumbis and Wolfe presented power as an umbrella concept comprising three elements:

- Force: explicit threat or use of military, economic, or coercive instruments.

- Influence: persuasion or inducements short of force.

- Authority: voluntary compliance of B with A’s directives, based on respect, legitimacy, or perceived expertise.

- Some scholars, such as Lerche and Said, prefer the term capability over power because the word “power” overemphasises coercion. Capability refers to the ability to act purposefully, ensuring a stronger connection between policy and action.

- Couloumbis and Wolfe distinguish capability from power by treating capability as the tangible and intangible attributes of states that allow them to exercise varying degrees of power in global interactions.

- Power is regarded as distinct from capability, yet related; most scholars still prioritise the use of the term power, given its established conceptual significance in political science.

- Greene and Elffers describe politics as an inescapable game of power, arguing that attempting to withdraw from power struggles leads to powerlessness, which in turn breeds dissatisfaction.

- According to their view, mastering the skills of power allows individuals and nations alike to operate more effectively, suggesting that competence in power enhances one’s ability to function in society and international relations.

International Relations Membership Required

You must be a International Relations member to access this content.