MSH 413

Indian Nationalism up to 1916

Semester – I

Unit I

Historiography of Indian Nationalism

Historiography is the study of historical interpretation. It helps us appreciate the intellectual context of history, instead of just viewing it as a simple recollection of events. Historiography is important for a variety of reasons. For example, it explains why historical events have been interpreted differently over time. Similarly, historiography allows us to study history with a critical eye. It aids us in understanding what biases may have influenced the historical record.

Schools of Historiography

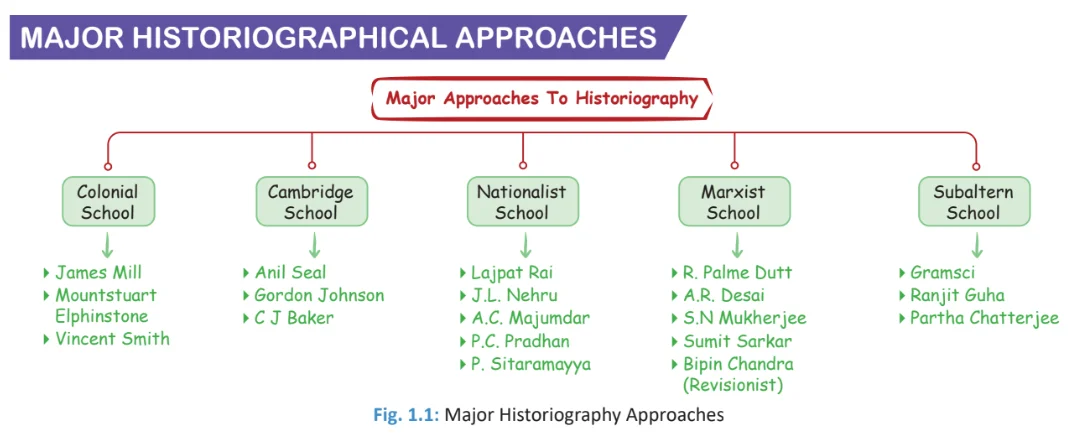

Main Schools: The modern history of India can be broadly divided into — the Colonial (or the Imperialist), Nationalist, Marxist, and Subaltern.

- Each approach has its distinct characteristics and ways of interpreting historical events.

- Other approaches: Communalist, Liberal and Neo-liberal, Cambridge and Feminist interpretations, which have also had a significant influence on how modern Indian history is written and understood.

Colonial School (Shift issue Bansal sir resolve it)

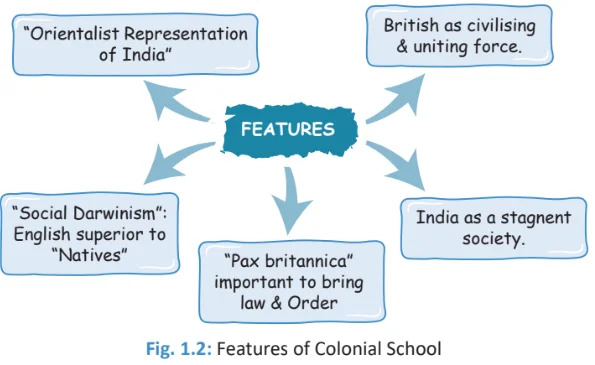

The “Colonial Approach” was a dominant perspective that held sway in India for much of the 19th century. This term is multifaceted in its meaning, encompassing two distinct dimensions.

- Historical Narratives and Ideological Influences: On one hand, it alludes to the historical narratives of colonial nations, while on the other, it relates to works influenced by the colonial ideology of control. In contemporary discussions, it is primarily in the latter context that historians delve into the realm of colonial historiography.

- Role of Documentation: The act of documenting colonial territories by colonial officials was intrinsically tied to their desire for dominance and the imperative of justifying colonial rule. Consequently, many of these historical accounts featured a critical portrayal of indigenous society and culture.

- Impact of the Colonial Approach and Western Values: Simultaneously, there was a palpable reverence for Western culture and values, accompanied by the exaltation of individuals who played pivotal roles in establishing colonial empires.

Key Details

- Major Proponents: James Mill (History of India), Mountstuart Elphinstone, Vincent Smith, Valentine Chirol (India Unrest).

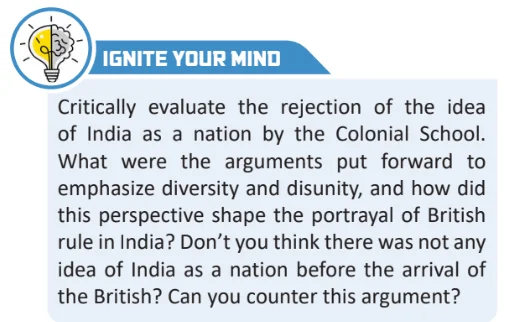

- Rejection of Idea of India as a Nation: The diversity and disunity of India were always emphasized by the colonialist thinkers as justification for the colonial rule which was considered to have united it.

-

- According to them, India was a conglomeration of different and often antagonistic religious, ethnic, linguistic, and regional groups that could never be welded into a nation.

- The strongest statement in this regard was provided by Valentine Chirol who, in his Indian Unrest (1910), asserted that India was a ‘mere geographical expression’, and even this geography was forged by the British.

- Benevolence of British Rule: This school viewed British rule in India as a benevolent and civilizing force that brought order, modernity, and progress to a supposedly backward and chaotic society.

- The above perspective was significantly articulated by Vincent Smith when he asserted that India would again become fragmented ‘if the hand of the benevolent despotism which now holds her in its iron grasp should be withdrawn’.

- British colonial administrators and historians tended to depict the movement as a series of sporadic and disconnected events, rather than a cohesive and concerted effort.

- Showing Merits in Colonial Rule: The Colonial School highlights the achievements of the British colonial administration, e.g., the introduction of modern education, railways, legal systems, and governance structures, as they had a positive influence on Indian society.

- Eurocentric Perspective: Indians are depicted as passive recipients of British policies and initiatives.

- It interpreted Indian history through a Eurocentric lens, evaluating developments in India about European benchmarks of progress and civilization.

Nationalist School

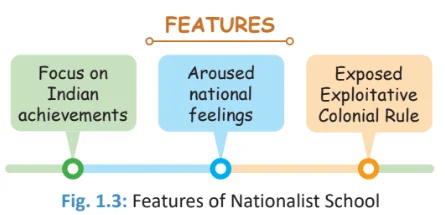

The Nationalist School of Historiography sought to reinterpret Indian history with a focus on the achievements and contributions of Indian civilization, in contrast to the colonial perspectives that often depicted India as a passive recipient of British influence.

Key Details

- Proponents: During the colonial period, this school was represented by political activists such as Lajpat Rai, A.C. Mazumdar, R.G. Pradhan, Pattabhj Sitaramayya, Surendranath Banerjee, C.F. Andrews, and Girija Mukerji. More recently, B.R. Nanda, Bisheshwar Prasa, and Amles Tripathi have made distinguished contributions to this approach.

- Stirred Nationalistic Feelings: This school contributed to the growth of nationalist feelings to unify people in the face of religious, caste, or linguistic differences or class differentiation. It looks at the national movement as a movement of the Indian people.

- Exposed Colonialism and Credited Anti-colonial Movement: It exposed the exploitative character of colonialism and also gave credit to the fact that India was in the process of becoming a nation, and the national movement was a movement of the people

- It celebrated India’s historical achievements and also criticized the negative impact of colonial rule.

- It highlighted economic exploitation, cultural degradation, and social disintegration under British administration.

- Subhas Chandra Bose, in his Indian Struggle, argued that India possessed ‘a fundamental unity’ despite endless diversity. Jawaharlal Nehru also spoke about ‘unity in diversity’ and cultural unity amidst diversity, a bundle of contradictions held together by strong but invisible threads.

- It celebrated India’s historical achievements and also criticized the negative impact of colonial rule.

- Limitation: Their major weakness is that they tend to ignore or underplay the inner contradictions of Indian society both in terms of class and caste. They tend to ignore the fact that while the national movement represented the interests of the people or nation as a whole (that is, of all classes vis-a-vis colonialism) it only did so from a particular class perspective, and that, consequently, there was a constant struggle between different social, ideological perspectives for hegemony over the movement.

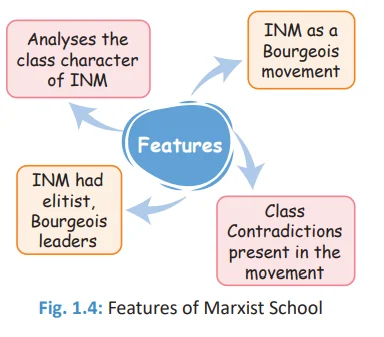

Marxist School

The Marxist historians have been critical of both the colonialist and nationalist views on Indian nationalism. They criticize the colonialist perspective for holding a discriminatory view of India and its people, while they criticize the nationalist commentators for seeking the roots of nationalism in the ancient past.

- They criticize both for not paying attention to economic factors and class differentiation in their analysis of the phenomenon of nationalism.

Key Details

- Proponents: The foundations of this school of historiography were laid by R. Palme Dutt and A.R. Desai. The later Marxist writings of S.N. Mukherjee, Sumit Sarkar, and Bipan Chandra have developed it further.

- R.P. Dutt formulated the most influential Marxist interpretation of Indian nationalism in his famous book India Today (1947).

- He stated that the revolt of 1857 “was in its essential character and dominant leadership the revolt of the old conservative and feudal forces and dethroned potentates”.

- R.P. Dutt formulated the most influential Marxist interpretation of Indian nationalism in his famous book India Today (1947).

- Bipin Chandra’s Revisionist Marxist School of Thought

- Bipan Chandra in his book ‘India’s Struggle for Independence’ (1988) has argued that the Indian nationalist movement was a popular movement of various classes, not exclusively controlled by the bourgeoisie.

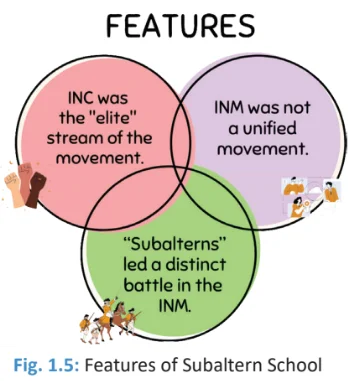

Subaltern School

The Subaltern school derives its theoretical inputs from the writings of the Italian Marxist, Antonio Gramsci. According to it, the organized national movement, which ultimately led to the formation of the Indian nation-state was hollow nationalism of the elites, while real nationalism was that of the masses, whom it calls the ‘subaltern’.

Key Details:

- Proponents: Ranjit Guha, Partha Chatterjee, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Dipesh Chakrabarty.

- Interpretation: The Subaltern school of historiography dismisses all previous historical writing as elite historiography.

- For them, the basic contradiction in Indian society in the colonial epoch was between the elite, both Indian and foreign, on the one hand, and the subaltern groups, on the other, and not between Colonialism and the Indian people

- The subaltern perspective highlighted a “structural dichotomy” between elite politics and subaltern action, where the two lived in separate mental worlds.

- They believed that the Indian people were never united in a common anti-imperialist struggle and that there was no such entity as the Indian national movement.

| “The historiography of Indian nationalism has for a long time been dominated by elitism”. He further says that this “blinkered historiography”, cannot explain Indian nationalism, because it neglects “the contribution made by the people on their own, that is, independently of the elite to the making and development of this nationalism”. The opening statement of the first volume of the Subaltern Studies.

Edited by Ranajit Guha (Sekhar Bandyopadhyay). |

- Strands of National Movements: They assert that there were two distinct movements or streams, the real anti-imperialist stream of the subalterns and the bogus national movement of the elite.

- The elite stream was led by the ‘official’ leadership of the Indian National Congress.

- Subaltern historiography first divides the movement into two and then accepts the neo-imperialist characterization of the elite stream.

- It too denies the legitimacy of the actual, historical anti-colonial struggle that the Indian people waged.

Conclusion

The study of historiography through various lenses, such as the Colonial, Nationalist, Marxist, and Subaltern schools offers a nuanced understanding of how history has been interpreted. Each school presents distinct perspectives, revealing the complexities and biases that shape historical narratives. Scholars like Partha Chatterjee argue for the integration of elite and subaltern politics, studying them in terms of their “mutually conditioned historicities.” The coexistence of elite and subaltern politics reveals the complex interactions that constituted the dominant themes in the period of Indian nationalism’s emergence and evolution.

Emergence of Indian Nationalism

Nationalism in India during the colonial period was indeed a political and cultural movement that sought to promote a sense of national identity and pride among Indians. The economic, social, and political changes brought about by British colonial rule played a significant role in shaping the growth of nationalism.

- The British policies of economic exploitation, land reforms, and the imposition of heavy taxes on Indian goods had a profound impact on the Indian economy and society. These policies led to the disruption of traditional industries, the impoverishment of rural communities, and the displacement of many artisans and craftsmen.

- As a result, a new class of educated Indians emerged, comprising lawyers, professionals, intellectuals, and businessmen. This class became the vanguard of the nationalist movement and played a crucial role in articulating and advocating for nationalist ideas.

- Literature, art, and music became powerful tools for expressing nationalist sentiments. Indian writers, poets, and artists depicted the richness of Indian culture, celebrated its history and traditions, and critiqued the oppressive nature of colonial rule. The works of writers such as Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Rabindranath Tagore, and Sarojini Naidu inspired a sense of pride and nationalism among Indians.

- Furthermore, the growth of nationalism in India was closely tied to the political activities of organizations like the Indian National Congress (INC). The INC, founded in 1885, initially aimed to seek representation for Indians in the colonial administration. However, over time, it became the leading platform for nationalist aspirations and demands for self-rule.

- Indian leaders like Dadabhai Naoroji, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Lala Lajpat Rai, and Mahatma Gandhi emerged as prominent figures within the nationalist movement. They advocated for political reforms, civil rights, and eventually, complete independence from British rule.

- The nationalist movement also witnessed various forms of protest and resistance against colonial rule. Boycotts of British goods, mass movements like the Non-Cooperation Movement and the Quit India Movement, and acts of civil disobedience were employed to challenge British authority and assert Indian identity.

- In summary, the economic, social, and political changes brought about by British colonial rule in India led to the emergence of Indian nationalism. It was a response to the challenges and aspirations of the Indian people who sought to assert their identity, protect their culture, and achieve self-determination. The growth of nationalism during this period laid the foundation for India’s eventual independence in 1947.

The growth of Indian nationalism is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that has evolved over several centuries. It is rooted in the aspirations of the Indian people for self-determination, cultural preservation, and political independence.

Here are some key factors that have contributed to the growth of Indian nationalism:

- Colonial Rule: The period of British colonial rule in India (1757-1947) played a significant role in shaping Indian nationalism. The oppressive policies, economic exploitation, cultural alienation, and political subjugation by the British ignited a sense of collective resistance among Indians. The Indian National Congress (INC), founded in 1885, became the main platform for nationalist activities.

- Socio-Religious Reform Movements: The 19th century witnessed the rise of socio-religious reform movements in India, such as the Brahmo Samaj and the Arya Samaj. These movements aimed to challenge social evils, promote education and revive indigenous cultural practices. They also played a crucial role in fostering a sense of pride in Indian heritage and creating a foundation for nationalist sentiments.

- Role of Intellectuals: Indian intellectuals and thinkers played a vital role in articulating and promoting nationalist ideas. Figures like Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Swami Vivekananda, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, and Rabindranath Tagore advocated for Indian cultural revival, self-reliance, and political freedom. Their writings and speeches inspired a sense of pride and unity among Indians.

- Partition of Bengal (1905): The British decision to partition Bengal along religious lines in 1905 sparked widespread protests and nationalist fervor. This event led to mass mobilization, boycotts, and a resurgence of cultural and political consciousness among Indians. The Swadeshi movement, which called for the use of indigenous goods, and the promotion of national education emerged as a powerful tool of resistance.

- Mahatma Gandhi and Nonviolent Resistance: Mahatma Gandhi emerged as the leader of the Indian National Congress in the early 20th century and became the face of the Indian nationalist movement. He advocated for nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience as a means to challenge British rule. His emphasis on self-reliance, grassroots mobilization, and inclusivity helped galvanize the masses and made the freedom struggle a mass movement.

- Unity in Diversity: India’s incredible diversity, encompassing various languages, religions, and cultural practices, has also contributed to the growth of Indian nationalism. The idea of “unity in diversity” has been a central theme, emphasizing the need to forge a common identity that transcends regional, linguistic, and religious differences.

- Impact of World War I and II: The participation of Indian soldiers in World War I and II on behalf of the British Empire had a profound impact on Indian nationalism. The disillusionment and sacrifices made by Indian soldiers, coupled with the contrast between the rhetoric of freedom and the reality of colonial rule, fueled nationalist sentiments and demands for independence.

- Post-Independence Nation-Building: After India gained independence in 1947, the process of nation-building further strengthened Indian nationalism. Policies promoting secularism, democratic governance, and social justice were enshrined in the Indian Constitution. Efforts to bridge regional and linguistic divides, promote economic development, and protect cultural diversity have contributed to a continued sense of Indian nationalism.

- It is important to note that the growth of Indian nationalism is a complex and ongoing process, and it continues to evolve in response to various social, political, and economic factors.

For over a century, the British exploited the Indian masses, breeding hatred and animosity toward them. The introduction of Western education opened the eyes of Indians to the British Raj’s colonial rule. Indian nationalism grew as a result of colonial policies and as a reaction to colonial policies. In fact, it would be more accurate to view Indian nationalism as the result of a confluence of factors.

Factors:

People United Politically Under the British Rule

- People became politically unified under British hegemony.

- There was one rule, one administrative framework, one set of laws, and one set of administrative officers that unified people politically.

- People became aware that vast India belonged to them, instilling a sense of nationalism in them.

Communication and Transportation Advancements

- Lord Dalhousie made a lasting contribution to Indians by introducing railways, telegraphs, and a new postal system. Roads were built from one end of the country to the other.

- Even though all of this was intended to serve imperial interests, the people of India capitalized on it. The train compartment mirrored a united India.

- It bridged the gap between them and gave them the sense that they all belonged to this vast India under the control of the British Raj.

Influence of Western Education

- The introduction of English education in 1835 marked a watershed moment in the British administration.

- Its primary goal was to educate the Indian masses so that they would be loyal servants of the British Raj.

- However, as time passed, English-educated Indians became forerunners in India’s sociopolitical, economic, and religious reforms.

- Raja Rammohan Roy, Swami Vivekananda, Ferozeshah Mehta, Dadabhai Naoroji, and Surendranath Banerjee all fought for liberty, equality, and humanitarianism.

- English-educated Indians gradually became the torchbearers of Indian nationalism, instilling national consciousness in the minds of millions of Indians.

India’s glorious past

- Several avenues in the field of oriental studies were opened up by the nineteenth-century Indian Renaissance.

- Western scholars such as Max Muller, Sir William Jones, Alexander Cunningham, and others translated several ancient Sanskrit texts from this land, establishing the glorious cultural heritage of India before the people.

- They inspired Indian scholars such as R.D. Banerjee and R.G. Bhandarkar. Mahan Mukhopadhyaya, Hara Prasad Astir, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, and others rediscovered India’s past glory from its history.

- This encouraged the people of India, who felt they were the ancestors of this country’s grand monarchs and were being ruled by foreigners. This fanned the flames of nationalism.

Movements for Socio-Religious Reform

- In the nineteenth century, the socio-religious reform movements led by Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Annie Besant, Syed Ahmad Khan, Swami Dayananda Saraswati, and Vivekananda brought about a national awakening in India.

- The abolition of Sati and the introduction of widow remarriage resulted in social reforms in India.

- Indians gained an understanding of the concepts of liberty, equality, freedom, and social disparities.

- This reawakened the people’s minds and instilled a sense of nationalism.

Growth of Vernacular Literature

- The influence of Western education compelled educated Indians to express the concepts of liberty, freedom, and nationalism through vernacular literature.

- They aimed to incite the masses to oppose British rule by instilling a sense of nationalism in them.

- Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s Anand Math and Dinabandhu Metra’s play Nil Darpan wielded enormous power over the people and instilled anti-British feelings in them.

- The play Baraga Purdahs by Bharatendu Harishchandra reflected the plight of the Indian masses under British rule.

- Aside from several eminent poets and writers in various languages, such as Rabindranath Tagore in Bengali, Vishnushastri Chipulunkar in Marathi, Laminate Bezbaruah in Assamese, Mohammad Husain Azad and Altaf Husain Ali in Urdu, their writings helped to rouse nationalism among the local people.

Role of Press

- Newspapers and magazines were critical in instilling a sense of nationalism in Indians.

- Raja Rammohan Roy edited Persian journals such as ‘Mirat-ul-Akhbar’ and the Bengali newspaper ‘Sambad Kaimiudi.’

- Similarly, several newspapers, such as Hindu Patriot, Bangalee, Amrit bazar patrika, Sudharani, and Sanjivani in Bengali; Indu Prakash in Maharashtra, Native Opinion, Kesari, Koh-i-Noor, Akhbar-i-Am and ‘The Tribune’ in Punjab, reflected British rule and aroused feelings of nationalism among people.

The First War of Independence’s Memory

- The memory of the Revolt of 1857 instilled in the Indians a sense of nationalism.

- After becoming aware of the British’s bad intentions, the heroic roles of Rani Laxmi Bai, Nana Saheb, Tayta Tope, and other leaders became fresh in the minds of the people.

- This instilled in the people a desire to fight the British.

The Ilbert Bill Controversy

- The Ilbert Bill was passed during Lord Ripon’s tenure as Viceroy. It gave Indian judges the authority to try the Europeans.

- It sparked outrage among Europeans, who pushed for a change in the bill, including a provision requiring an Indian to try a European in the presence of a European witness.

- This clearly exposed the British authorities’ deception and projected their racial animosity.

Antagonism Between Races

- The British considered themselves superior to Indians and never offered them good jobs regardless of their merits or intelligence.

- The Indian Civil Service examination was held in England, and the age limit was 21.

- Aurobindo Ghosh passed the written exam but was disqualified from horseback riding and did not pass the ICS exams. The British purposefully disqualified them.

- They believed that Indians were brown and unfit to rule and that it was the white man’s responsibility to rule them. This inflamed people’s resentment of British rule.

Economic Exploitation

- Britishers economically exploited India by draining wealth from India to Britain, as expressed in Dada Bhai Naoroji’s ‘Drain Theory.’

- Following the Industrial Revolution in England, the British needed raw materials and markets, which were met by draining the raw materials of India and using Indian markets.

- The landlords, guided by Britishers, exploited the Indian masses and further exploited the Indian economy.

- The ‘Drain Theory’ of Dadabhai Naoroji, Ranade, and G.V. Joshi raised awareness about the exploitation of Indian handicrafts, which mirrored the exploitative nature of Britishers toward the Indian economy.

- This ruined India’s factories, handicrafts, and economy, leaving the Indian people impoverished and filled with resentment toward the British.

Formation of the Indian National Congress

- The Indian National Congress was founded in 1885. It expressed the Indian people’s desire in front of the British.

- The mass movements and leaders played an important role in the development of people’s national consciousness.

- The Indian National Congress enabled the Indians to wage ideological battles against the British, resulting in India’s independence.

- Moderates such as Dada Bhai Naoroji and S.N. Banerjee, as well as extremists such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Bipin Chandra Pal, and Lala Lajpat Rai, all played important roles in instilling a sense of nationalism in Indians.

Bengal’s Partition (1905)

- Lord Curzon, the British viceroy, was in charge of partitioning Bengal in 1905.

- Since 1765, Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa had been united as a single province of British India.

- By 1900, the province had grown too large for a single administration to handle. East Bengal had been overlooked in favor of West Bengal and Bihar due to its isolation and poor communication.

- Partition was opposed by the Hindus of West Bengal, who controlled the majority of Bengal’s commerce, professional, and rural life. They saw the partition as an attempt to suffocate nationalism in Bengal, where it was stronger than elsewhere.

- The Indian National Congress was transformed from a middle-class pressure group into a nationwide mass movement as a result of this.

Bengal’s Swadeshi Movement

- The Swadeshi Movement arose from Bengal’s anti-partition movement.

- The decision escalated the protest meeting, resulting in the passage of a Boycott resolution in a massive meeting held in Calcutta Town Hall, as well as the formal proclamation of the Swadeshi Movement.

- The extremists dominated the Swadeshi Movement in Bengal. They proposed new forms of struggle. The movement primarily advocated a boycott of foreign goods, as well as mass mobilization through public meetings and processions.

- Self-sufficiency, or ‘Atma Shakti,’ as well as Swadeshi education and enterprise, were emphasized.

- Several families remained active to ensure mass participation, and songs written by Rabindranath Tagore, Rajanikanta Sen, Dwijendralal Ray, Mukunda Das, and others inspired the masses in the cultural sphere.

- Soon after, the movement spread to other parts of the country, with Tilak leading in Pune and Bombay, Lala Lajpat Rai and Ajit Singh leading in Punjab, Syed Haider Raza leading in Delhi, and Chidambaram Pillai leading in Madras.

Social and Religious Reform Movements of the 19th Century

INTRODUCTION

The conquest of India by the British during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries exposed some serious weaknesses and drawbacks of Indian social institutions. As a consequence several individuals and movements sought to bring about changes in the social and religious practices with a view to reforming and revitalizing the society. These efforts, collectively known as the Renaissance, were complex social phenomena. It is important to note that this phenomenon occurred when India was under the colonial domination of the British.

THE NEED FOR REFORM

An important question for discussion is about the forces which generated this awakening, in India. Was this a result of the impact of the West? Or was it only a response to the colonial intervention? Although both these questions are inter-related, it would be profitable to separate them for a clear understanding. Another dimension of this is related to the changes taking place in Indian society leading to the emergence of new classes. For this perspective, the socio-religious movements can be viewed as the expression of the social aspirations of the newly emerging middle class in colonial India.

The early historical writings on reform movements have traced their origin primarily to the impact of the West. One of the earliest books to be written on the subject by J.N. Farquhar (Modern Religious Movements in India, New York, 1924), held that:

The stimulating forces are almost exclusively Western, namely, English education and literature, Christianity, Oriental research, European science and philosophy, and the material elements of Western civilization.

Several historians have repeated and further elaborated this view. Charles Heimsath, for instance, attributed not only ideas but also the methods of organization of socio-religious movements to Western inspiration.

The importance of Western impact on the regenerative process in the society in nineteenth century is undeniable. However, if we regard this entire process of reform as a manifestation of colonial benevolence and limit ourselves to viewing only its positive dimensions, we shall fail to do justice to the complex character of the phenomenon. Sushobhan Sarkar (in Bengal Renaissance and Other Essays, New Delhi, 1970) has drawn our attention to the fact that “foreign conquest and domination was bound to be a hindrance rather than a help to a subject people’s regeneration”. How colonial rule acted as a factor limiting the scope and dimension of nineteenth century regeneration needs consideration and forms an important part of any attempt to grasp its true essence.

The reform movements should be seen as a response to the challenge posed by the colonial intrusion. They were indeed important just as attempts to reform society but even more so as manifestations of the urge to contend with the new situation engendered by colonialism. In other words the socioreligious reform was not an end in itself, but was integral to the emerging anti-colonial consciousness.

Thus, what brought about the urge for reform was the need to rejuvenate the society and its institutions in the wake of the colonial conquest. This aspect of the reform movement, however, introduced an element of revivalism, a tendency to harp back on the Indian past and to defend Indian culture and civilization. Although this tended to impart a conservative and retrogressive character to these movements, they played an important role in creating cultural consciousness and confidence among the people.

REFORM MOVEMENTS

The earliest expression of reform was in Bengal, initiated by Rammohun Roy. He founded the Atmiya Sabha in 1814, which was the forerunner of Brahmo Samaj organized by him in 1829. The spirit of reform soon manifested itself in other parts of the country. The Paramahansa Mandali and Prarthana Samaj in Maharashtra and Arya Samaj in Punjab and other parts of north India were some of the prominent movements among the Hindus. There were several other regional and caste movements like Kayastha Sabha in U.P. and Sarin Sabha in Punjab. Among the backward castes too reformation struck roots. The Satya Shodhak Samaj in Maharashtra and Sri Narayana Dharma Paripalana Sabha in Kerala. The Ahmadiya and Aligarh movements, the Singh Sabha and the Rehnumai Mazdeyasan Sabha represented the spirit of reform among the Muslims, the Sikhs and the Parsees respectively.

The following features are evident from the above account:

i) Each of these reform movements was confined, by and large to one region or the other. Brahamo Samaj and the Arya Samaj did have branches in different parts of the country yet they were more popular in Bengal and Punjab respectively than anywhere else.

ii) These movements were confined to particular religions or castes.

iii) An additional feature of these movements was that they all emerged at different points of time in different parts of the country. For example in Bengal reform efforts were afoot at the beginning of the nineteenth century, but in Kerala they came up only towards the end of the nineteenth century. Despite this, there was considerable similarity in their aims and perspectives. All of them were concerned with the regeneration of society through social and educational reforms even if there were differences in their methods.

Arya Samaj

- The Arya Samaj was a Hindu reform organisation founded by Swami Dayanand Saraswati on April 7, 1875 in Bombay.

- Leaders and nationalists namely Pandit Guru Dutt, Lala Lajpat Rai, Swami Shraddhananda and Lala Hansraj were drawn into this organisation.

- The members of this organisation stood against idol worship, superstitious rituals, animal sacrifice, polytheism and priesthood.

- Back to Vedas was the motto of this organisation. Its founder, Swami Dayanand Saraswati claimed that any scientific theory or invention which was thought to be of modern origin was actually derived from the Vedas.

- Arya Samaj focussed on female education, abolition of child marriage and stood for permitting widow remarriage on certain cases.

- This organisation played a key role in changing the religious perceptions of the Indians. It was largely a proselytizing movement which led to the rise of a militant Hindu consciousness in the 19th and 20th centuries

Arya Mahila Samaj

- The Arya Mahila Samaj also called Arya Women’s Society was founded by Pandita Ramabai in 1882. Soon after the death of her husband, she moved to Pune where she was influenced by the ideals of Brahmo samaj and started the Arya Mahila Samaj.

- This organisation was started with an aim to elevate the position of women in Indian society. It promoted women education and deliverance from the oppression of child marriage which was then prevalent in the society. It worked on improving the conditions of women in various fronts.

- In addition to this, Pandita Ramabai also founded Sharada Sadan for helping the deserted and abused widows, particularly the young ones.

Ahmadiyya Movement

- The Ahmaddiyya movement was a Islamic revivalist movement that took place in the late 19th century.

- This movement was started by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian in 1889 to fight against the polemics of christian missionaries and that of the Arya Samaj.

- Being influenced by the western liberalism and the religious reform movement of the Hindus, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad based this movement on the lines of universal religion of all humanity.

- This movement played a crucial role in spreading western education among the Indian Muslims and it also stood against the jihad which was a sacred war against the non-muslims.

Atmiya Sabha

- Atmiya Sabha, also known as the society of friends, was established by Raja Rammohan Roy in 1814 at Calcutta

- The members of this sabha often conducted sessions and philosophical discussions on the monothestic ideals of the Vedanta.

- They campaigned against idol worship, superstitious beliefs and practices, social ills such as child marriage, sati ete and caste rigidities.

- Some of the well known members of Atmiya Sabha were Brindaban Mitra, Prasanna Kumar Tagore, Dwaraka Nath Tagore and Sivaprasad Misra.

Brahmo Samaj

- Brahmo Samaj, which was earlier known as the Brahmo Sabha, was founded by Raja Rammohan Roy in August 1828. Its initial landmark began in Bengal.

- The Atmiya Sabha which was established by him in 1814, took the shape of Brahmo Samaj in 1828.

- This religious society criticized the idolatry and denounced social evils such as sati, child marriage, ete and they laid great emphasis on human dignity. They discarded the faith in incarnations and were against the caste system.

- The agenda of Brahmo Samaj was to purify Hinduism and to preach monotheism. It was purely based on the Upanishads and Vedas,

- Following the death of Raja Rammohan Roy, the religious society was split at various times in the course of the 19th century.

Deoband Movement

- The Deoband movement was started by Mohammad Qasim Nanotavi and Rashid Ahmed Gangohi in 1866 at the Darul Uloom. It was a revivalist movement which was organised by the orthodox section of the Muslims.

- The main objectives of this movement were to propagate the teachings of Quran and Hadis among the Muslims and to support jihad against the foreign rulers. Repeated manifestations around purification of ritual practices was the vital part of the movement.

- This Deoband school was originally designed to prepare students for their role as members of the ulama.

Deva Samaj

- Deva Samaj was a religious sect founded by Shiv Narain Agnihotri in 1887 at Lahore.

- The samaj emphasised on the supremacy of Guru and the need for good actions.

- It advocated widow remarriage, women education, social integration of castes and the abolition of child marriage and sati.

- In 1892, it’s founder advocated the dual worship of God and himself and later he discarded the worship of God. Apart from that, they also prescribed moral ethics such as abstaining from intoxicants, violence, bribery and gambling activities.

- The philosophies followed by the Deva Samaj and their teachings were compiled in a book called Deva Shastra.

Faraizi Movement

The Faraizi movement, also known as the Fara’id movement, was started by Haji Shariat Ullah in 1818 in East Bengal

Initially the movement focussed on religious purification and discarding of improper beliefs and un-islamic practices.

It insisted the Bengali muslims to follow the obligatory duties of Islam such as daily prayers, fasting in Ramzan, paying charities and pilgrimage to Mecca.

Around 1830’s, the movement became enmeshed in political and economic issues. Due to the clash between Faraizi peasants and Hindu landlords on paying taxes, many of the Fara’id peasants were suspected and persecuted.

Eventually in 1840, the movement was taken over by Dudu Miyan, who turned the social and religious movement into a revolutionary movement.

Prarthana Samaj

- Prarthana Samaj was founded by Atmaram Pandurang with the help of Keshab Chandra Sen in Bombay in 1867. Mahadev Gobind Ranade was the man behind the popularity and work done by the samaj.

- Paramahansa Sabha which was a secret society working on spreading the liberal ideas, was the precursor of Prarthana Samaj.

- Similar to Brahmo Samaj, this religious society also preached monotheism, denounced idolatry and priestly dominations

- Their 4 point social agenda was

- Disapproval of caste system

- Widow remarriage

- Women’s education

- Raising the marriage age for both males and females.

- The samaj succeeded in establishing libraries, free reading rooms, schools and orphanages in some parts of the country.

Ramakrishna Movement

- In the second half of the 19th century, the Brahmo Samaj of Bengal began to weaken and it paved the way for the emergence of the Ramakrishna movement.

- Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, a great teacher who expressed and taught great and deep philosophical thoughts in simple language, found many followers. He believed that service to man was service to God, for man was the embodiment of God on earth. He was a staunch believer of the ideology that there was an underlying unity among all religions and only the methods of worship were different.

- His teachings were spread across the country by his followers and it came to be known as the Ramakrishna movement.

Ramakrishna Mission

- After the demise of Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, Swami Vivekananda founded the Ramakrishna mission in 1896. He spreaded the messages and teachings of Ramakrishna Paramahamsa and also tried to reconcile them to the needs of contemporary society.

- This mission believed in idolatry and the philosophy of Vedanta.

- The key objective of the mission was to render social service in the country. To serve that purpose, a number of schools, orphanages, hospitals and libraries were established throughout the country.

- Apart from that, it offered help to the people who were affected by the natural calamities such as earthquakes, tsunami, floods, famines and epidemics.

Satyashodhak Samaj

- This society was founded by Jyotiba Phule in Pune on 24 September 1873.

- He founded this social reform society with an aim to educate the lower sections of the society and make them aware of their rights. By doing this, he tried to liberate the depressed class of Indian society.

- Only the members belonging to lower castes or shudra samaj were admitted into the society.

- It rejected the caste system and was also against the social and political superiority of the Brahmanas. They also rejected the Upanishads, Vedas and the dominance of the Aryan society.

- The society emphasized that no medium or intermediaries were required to communicate with gods and tried to set the people free from all religious and superstitious beliefs.

Tattvabodhini Sabha

- The Tattvabodhini Sabha was founded by Debendranath Tagore in Calcutta on October 6, 1839. At the time of Establishment, it was known as the Tattvaranjani Sabha.

- It is considered to be the splinter group of the Brahmo Samaj.

- They were formed with an objective to promote a rational and humanist form of Hinduism based on Upanishads and Vedas.

- It made a systematic study of India’s glorious past with a rational outlook and spread them among the intellectuals of Bengal. Tattvabodhini Sabha propagated the social welfare programmes through their monthly journal named Tattvabodhini Patrika.

- Pandit Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar, Rajendra Lal Mitrs, Peary Chand Mitra, Akshay Kumar Datta, Tara Chand Chand Chakravarthy and few other people from the elite section of the society became the members of the sabha.

Theosophical Society

- The Theosophical Society was founded by Madame H.P.Blavatsky and Colonel M.S.Olcott in 1875 in the United States. Later in 1882, the headquarters of the society was shifted from the United States to Madras in India.

- In 1888, Annie Besant joined the society in England and it was under her leadership, the movement became popular in India.

- The beliefs of the society were a mixture of religion, philosophy and occultism. It believed in the universal brotherhood of man and transmigration of soul, doctrine of reincarnation and karma.

- The ideologies of the society was inspired from the Upanishads, Samkhya, Yoga and Vedantie traditions. It also preached that by contemplation, prayer and revelation, one could establish a special relation between a person’s soul and God.

Young Bengal Movement

- The origin of the Young Bengal movement is owed to Henry Vivian Derozio, who was the principal inspiration behind this movement.

- He was a teacher at Hindu college of Calcutta from 1826t0 1831. Being inspired by the ideals of the French revolution, he taught about rational thinking, liberty, equality and freedom to his students and initiated provocative ideas in their minds.

- His students, who were later called the Derozians, spread the ideas and teaching of Henry Vivian Derozio to the people in Bengal.

- They criticized irrational orthodox practices and supported the rights of women, freedom of press, supported ryots against Zamindars, and argued in favour of the Indian appointments to higher Government offices.

Other Social And Religious Reform Movements Of 19th Century

- In 1887, Bharat Dharma Mahamandala was started by Pandit Din Dayalu Sharma, in order to bring together the orthodox educated Hindus and work together for the preservation of Sanatan Dharma.

- Another Hindu orthodox society named Dhara Sabha was founded by Radhakant Deb in 1839. The society promoted western education and advocated abolition of sati practice.

- The Radhaswami movement was started by Tulsi Ram of Agra in 1861. The followers of this movement believed in one supreme being, the supremacy of Guru, simple social life and company of pious people.

- The Veda Samaj was formed by Keshab Chandra Sen and K.Sridharalu Naidu in 1864. After studying the Brahmo Samaj movement from Calcutta, K.Sridharalu Naidu renamed the movement as Brahmo Samaj of South India.

- In 1892, the Madras Hindu Social Reforms Association was founded by Veresalingam Pantulu. It was a social purity movement and it fought against the devadasi system that was prevalent then in south India.

- In the 1860s, the Satya Mahima Dharma was founded by Mukund Das (Mahima Gosain) along with Govinda Baba and Bhima Bhoi, to preach the existence of only one god (Alakh Param Brahma) who was formless.

- The Paramahansa Mandali was founded by Bal Shastri Jambhekar and Dadoba Panderung in 1849. The seven principles of this movement were: God alone should be worshipped; spiritual religion is one; real religion is based on love and moral conduct; every individual should have a freedom of thought; our actions and speech should be consistent with reason; mankind is one caste; and the right kind of knowledge should be given to all.

- In 1888, a movement called Aravipuram movement was started by Sri Narayan Guru. This movement defied the religious and social restrictions that were placed on the Ezhava community (low caste).

- Baba Dayal Das launched the Nirankari movement in the 1840s. This movement emphasised on the worship of formless God (Nirankar) and rejected the idolatry and rituals associated with it.

- In 1873, Thakur Singh Sandhawalia and Giani Gian Singh founded the Singh Sabha of Amritsar, It was a Sikh religious reform movement of the 19th century. They aimed to restore the purity of Sikhism and to involve the Britishers in educational programmes of the Sikhs.

SCOPE OF REFORMS

The reform movements of the nineteenth century were not purely religious movements. They were socio-religious movements. The reformers like Rammohun Roy in Bengal, Gopal Hari Deshmukh (Lokhitavadi) in Maharashtra and Viresalingam in Andhra advocated religious reform for the sake of “Political advantage and social comfort”. The reform perspectives of the movements and their leaders were characterised by recognition of interconnection between religious and social issues. They attempted to make use of religious ideas to bring about changes in social institutions and practices. For example, Keshub Chandra Sen, an important Brahmo leader, interpreted the “unity of godhead and brotherhood of mankind” to eradicate caste distinctions in society.

The major social problems which came within the purview of the reform movements were:

- Emancipation of women in which sati, infanticide, child and widow marriage were taken up

- Removal of Casteism and untouchability

- Spread of education for bringing about enlightenment in society

In the religious sphere the main issues against which the reform movements were directed were as follows:

- Idolatry

- Polytheism

- Religious superstitions

- Exploitation by priests

METHODS OF REFORM

In the attempts to reform the socio-religious practices several methods were adopted. Four major trends out of these are as follows:

Reform from Within

The technique of reform from within was initiated by Rammohun Roy and followed throughout the nineteenth century. The advocates of this method believed that any reform in order to be effective had to emerge from within the society itself. As a result, the main thrust of their efforts was to create a sense of awareness among the people. They tried to do this by publishing tracts and organizing debates and discussions on various social problems. Rammohun’s campaign against sati, Vidyasagar’s pamphlets on widow marriage and B.M. Malabari ‘s efforts to increase the age of consent are the examples of this.

Reform through Legislation

The second trend was represented by a faith in the efficacy of legislative intervention. The advocates of this method — Keshub Chandra Sen in Bengal, Mahadev Govind Ranade in Maharashtra and Viresalingam in Andhra — believed that reform efforts cannot really be effective unless supported by the state. Therefore, they appealed to the government to give legislative sanction for reforms like widow marriage, civil marriage and increase in the age of consent. They, however, failed to realize that the interest of the British government in social reform was linked with its own narrow politico-economic considerations and that it would intervene only if it did not adversely affect its own interests. Moreover, they also failed to realize that the role of the legislation as an instrument of change in a colonial society was limited because the lack of sanction of the people.

Reform through Symbol of Change

The third trend was an attempt to create symbols of change through nonconformist individual activity. This was limited to the ‘Derozians’ or ‘Young Bengal’ who represented a radical stream within the reform movement. The members of this group, prominent of them being Dakshinaranjan Mukherjee, Ram Gopal Ghose and Krishna Mohan Banerji, stood for a rejection of tradition and revolt against accepted social norms. They were highly influenced by “the regenerating new thought from the West” and displayed an uncompromisingly rational attitude towards social problems. Ram Gopal Ghose expressed the rationalist stance of this group when he declared: “He who will not reason is a bigot, he who cannot is a fool and he who does not is a slave”. A major weakness of the method they adopted was that it failed to draw upon the cultural traditions of Indian society and hence the newly emerging middle class in Bengal found it too unorthodox to accept.

Reform through Social Work

The fourth trend was reform through social work as was evident in the activities of Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Arya Samaj and Ramakrishna Mission. There was a clear recognition among them of the limitations of purely intellectual effort if undertaken without supportive social work. Vidyasagar, for instance, was not content with advocating widow remarriage through lectures and publication of tracts. Perhaps the greatest humanist India saw in modern times, he identified himself with the cause of widow marriage and spent his entire life, energy and money for this cause.

Despite that, all he was able to achieve was just a few widow marriages. Vidyasagar’s inability to achieve something substantial in practical terms was an indication of the limitations of social reform effort in colonial India.

The Arya Samaj and the Ramakrishna Mission also undertook social work through which they tried to disseminate ideas of reform and regeneration. Their limitation was an insufficient realization on their part that reform on the social and intellectual planes is inseparably linked with the overall character and structure of the society. Constraints of the existing structure would define the limits which no regenerative efforts on the social and cultural plane could exceed. As compared to the other reform movements, they depended less on the intervention of the colonial state and tried to develop the idea of social work as a creed.

IDEAS

Two important ideas which influenced the leaders and movements were rationalism and religious universalism.

Rationalism

A rationalist critique of socio-religious reality generally characterized the nineteenth century reforms. The early Brahmo reformers and members of ‘Young Bengal’ had taken a highly rational attitude towards socio-religious issues. Akshay Kumar Dutt, who was an uncompromising rationalist, had argued that all natural and social phenomena could be analysed and understood by our intellect purely in terms of physical and mechanical processes. Faith was sought to be replaced by rationality and socio-religious practices were evaluated from the standpoint of social utility. In Brahmo Samaj the rationalist perspective led to the repudiation of the infallibility of the Vedas and in Aligarh movement founded by Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan, to the reconciling of the teaching of Islam with the needs and requirements of modern age. Holding that religious tenets are not immutable, Sayyid Ahmad Khan emphasised the role of religion in the progress of society: if religion did not keep in step with the times and meet the demand of society, it would get fossilized as had happened in the case of Islam in India.

Although reformers drew upon scriptural sanction e.g., Rammohun’s arguments for the abolition of sati and Vidyasagar’s for widow marriage, social reforms were not always subjected to religious considerations. A rational and secular outlook was very much evident in positing an alternative to the then prevalent social practices. In advocating widow marriage and opposing polygamy and child marriage, Akshay Kumar was least concerned with searching for any religious sanction or finding out whether they existed in the past. His arguments were mainly based on their noticeable effects on society. Instead of depending on the scriptures, he cited medical opinion against child marriage.

Compared to other regions there was less dependence on religion in Maharashtra. To Gopal Hari Deshmuk whether social reforms had the sanction of religion was immaterial. If religion did not sanction them he advocated that religion itself be changed, as what was laid down in the scriptures need not necessarily be of contemporary relevance.

Religious Universalism

An important religious idea in the nineteenth century was universalism — a belief in the unity of godhead and an emphasis on religions being essentially the same. Rammohun considered different religions as national embodiments of universal theism and he had initially conceived Brahmo Samaj as a universalist Church. He was a defender of the basic and universal principles of all religions — monotheism of the Vedas and unitarianism of Christianity — and at the same time he attacked the polytheism of Hinduism and trinitarianism of Christianity. Sayyid Ahmad Khan echoed almost the same idea: all prophets had the same din (faith) and every country and nation had different prophets. This perspective found clearer articulation in Keshub Chandra Sen who tried to synthesise the ideas of all major religions in the breakaway Brahmo group, Nav Bidhan, that he had organized. “Our position is not that truths are to be found in all religions, but all established religions of the world are true.”

The universalist perspective was not a purely philosophic concern; it strongly influenced political and social outlook, until religious particularism gained ground in the second half of the nineteenth century. For instance, Rammohun considered Muslim lawyers to be more honest than their Hindu counterparts and Vidyasagar did not discriminate against the Muslim in his humanitarian activities. Even to the famous Bengali novelist Bankim Chandra Chatterji, who is credited with a Hindu outlook, dharma rather than specific religious affiliation was the criterion for determining the superiority of one individual over the other. This, however, does not imply that religious identity did not influence the social outlook of the people. In fact it did so very strongly. The reformer’s emphasis on universalism was an attempt to contend with this particularising pull. However, faced with the challenge of colonial culture and ideology, universalism, instead of providing the basis for the developing of a broader secular ethos, retreated into religious particularism.

SIGNIFICANCE

In the evolution of modern India the reform movements of the nineteenth century have made very significant contribution. They stood for the democratization of society, removal of superstition and abhorent customs, spread of enlightenment and the development of a rational and modern outlook. Among the Muslims the Aligarh and Ahmadiya movements were the torch bearers of these ideas. Ahmadiya movement, which took a definite shape in 1890 due to the inspiration of Mirsa Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian, opposed jihad, advocated fraternal relations among the people and championed Western liberal education. The Aligarh movement tried to create a new social ethos among the Muslims by opposing polygamy and by advocating widow marriage. It stood for a liberal interpretation of the Quran and propagation of Western education.

The reform movements within the Hindu community attacked a number of social and religious evils. Polytheism and idolatry which negated the development of individuality or supernaturalism and the authority of religious leaders which induced the habit of conformity were subjected to strong criticism by these movements. The opposition to caste was not only on moral and ethical principles but also because it fostered social division. Anti-casteism existed only at a theoretical and limited level in early Brahmo movement, but movements like the Arya Samaj, Prarthana Samaj and Rama Krishna Mission became uncompromising critics of the caste system. More trenchant criticism of the caste system was made by movements which emerged among the lower castes. They unambiguously advocated the abolition of caste system, as evident from the movements initiated by Jotiba Phule and Sri Narayana Guru. The latter gave the call — only one God and one caste for mankind.

The urge to improve the condition of women was not purely humanitarian; it was part of the quest to bring about the progress of society. Keshub Chandra Sen had voiced this concern: “no country on earth ever made sufficient progress in civilization whose females were sunk in ignorance”.

An attempt to change the then prevalent values of the society is evident in all these movements. In one way or the other, the attempt was to transform the hegemonic values of a feudal society and to introduce values characteristic of a bourgeois order.

WEAKNESSES AND LIMITATIONS

Though the nineteenth century reform movements aimed at ameliorating the social, educational and moral conditions and habits of the people of India in different parts of the country, they suffered from several weaknesses and limitations. They were primarily urban phenomena. With the exception of Arya Samaj, and the lower caste movements which had a broader influence, on the whole the reform movements were limited to upper castes and classes. For instance, the Brahmo Samaj in Bengal was concerned with the problems of the bhadralok and the Aligarh movement with those of the Muslim upper classes. The masses generally remained unaffected.

Another limitation lay in the reformers’ perception of the nature of the British rule and its role toward India. They believed quite erroneously, that the British rule was God sent and would lead India to the path of modernity. Since their model of the desirable Indian society was like that of the 19thcentury Britain, they felt that the British rule was necessary in order to make India Britain-like. Although they perceived the socio religious aspects of the Indian society very accurately, its political aspect, that of a basically exploitative British rule, was missed by the reformers.

Unit II

MA History Semester I Membership Required

You must be a MA History Semester I member to access this content.

Unit III

MA History Semester I Membership Required

You must be a MA History Semester I member to access this content.

Unit IV

MA History Semester I Membership Required

You must be a MA History Semester I member to access this content.

Unit V

MA History Semester I Membership Required

You must be a MA History Semester I member to access this content.