Unit I

China's Confrontation with External and Internal Crisis

Introduction: Land, Politics and Culture

Ancient History

The country’s ancient history is still very much alive in the everyday activities of today’s China. While sometimes shadowed by the growing technological society, historical traditions such as Confucianism and the complex dynasty system still have an obvious influence on modern-day China. Before you begin your China tour, enhance your experience with some background information on the origins of Chinese civilization.

Supposed to have co-existed in areas around the Yellow River as independent principalities from 2200-221 BC, it is believed that the Xia were conquered by the Shang, who were than later conquered by the Zhou. Little is known about the Xia Dynasty (2200 – 1750 BC). In fact, the Xia were once debated by historians to be a myth. While no writing examples have survived, it is almost certain that their writing systems were a precursor to the Shang dynasty’s “oracle bones” system. Shang Dynasty (1750 –1040) has produced the earliest records of an absolute Chinese writing system. These people were very advanced in working with bronze. Human sacrifice was also a large part of their culture. Later dynasties, upon uncovering the mass graves, replaced the Shang sacrifices with terra cotta figures – the clay statues resembling an underground army.

The Shang were conquered in 1040 by the Zhou Dynasty. The Zhou practiced a system of a father-son king succession pattern, and unlike the Shang, rejected human sacrifice. The Zhou were able to maintain peace and stability for a few hundred years, until 771 BC, when the capital was stormed by “barbarians” from the west. After this the Zhou moved east causing a decline in their power.

On a tour of China you will learn the origins of concepts, and ideas birthed during this period that continue to be studied and practiced today. Some of the most important of such concepts are Confucianism, Legalism, and Daoism (which profoundly influenced the later development of Zen Buddhism). Confucius (500BC) believed that moral men make good rulers and that virtue was attainable by following the proper behaviors. Confucius is also responsible for creating the thought that the Emperor had the mandate of heaven to rule, or was the “Son of Heaven”. Legalism called for the suppression of dissenters, and sought to unify a then divided China through control and imposition of fear. The concept of “loyal opposition” did not exist, since the Emperor had the mandate of heaven to rule. Small battles between divisions soon gave birth to a period characterized by massive armies and long battles.

Early Empire (221BC-589AD)

The warring years ended in 221 BC with the conquering Qin Shihuangdi, a devout legalist. Qin was responsible for linking together old defensive walls to create the beginnings of a China wall (which would later be built by the Ming Dynasty into the Great Wall it is today). Qin died in 210 BC, and not long after the dynasty fell to the Han. The Han perfected the bureaucratic process that all successive dynasties would follow. By developing a system based on the proper behavior from the Confucian Classics and loyalty to the Emperor, the Han made managing a country of roughly 60 million people possible for many years. Due to tribal raiders from the north and a huge population shift from the center of the empire, the Han dynasty lost control in 220 AD, plunging China into 350 years of chaos and disunity. During this period of “three kingdoms”, the ‘barbarians’ maintained control in the north, while the Han resided predominantly in the south. The other notable change was the introduction of Buddhism from India, which then merged with Daoism to form a popular religion and helped shape the emerging culture.

The Second Empire (589-1644)

The Sui Dynasty, while their rule was not exceptionally long, managed to re-unify China under one Emperor. Even though Sui, and the Tang to follow, were based in the north and considered part ‘barbarian’, these dynasties are accepted as being Chinese. The Tang are considered one of the greatest dynasties and extended China’s borders significantly during their rule. The only woman Empress took power during this dynasty, and a devastating eight-year civil war shattered Tang control and the country disintegrated during the following 150 years. The Song Dynasty was the next to step up to re-unify China; this dynasty ushered in a period of tremendous technological, economic and cultural growth. The Song developed agricultural and farming techniques that allowed for sufficient food distribution. These techniques can still be found in use today in remote areas of China, as you may see firsthand on a China tour. The Mongol invasion from the north slowly pushed this dynasty out of power.

The time of Mongol rule, while a dynasty in essence, is considered only an occupation. During this period, reactionary Neo-Confucianism was developed, which led to the Ming Dynasty’s rise to power. The Ming were responsible for moving the capital to Beijing, building the Great Wall and the Forbidden City. The Qing (or Manchu) Dynasty was the last to rule starting in 1644. Under the Qing the arts flourished, and China cut itself off from contact with the developing western nations. Rampant corruption, territoriality of western nations over China and decentralization led to many rebellions. One such rebellion was the Taiping, which lead to the final the collapse of the Qing Dynasty in 1911. On your tour of China you will find it interesting to observe the transformation the country has experienced and how present day China has come into existence.

See below a brief timeline of the history of the dynasties as well as what each is most noted for:

Shang Dynasty (1766-1122 BCE) –Silk weaving invented. Chinese writing developed.

Zhou Dynasty (1122-221 BCE) – Iron casting and multiplication tables. Large scale irrigation. Confucius teaches on code of behavior.

Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE)– Strict law code and tax system implemented. Writing, weights, and measures are standardized. Began construction of the Great Wall and Xi’an’s army of terracotta warriors.

Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) – Buddhism arrives from India. Trade routes to India and Persia are established. Paper invented.

WARRING STATES (220 CE – 581) – Multiple warring kingdoms keep China in chaos.

Sui Dynasty (589-618) – Powerful emperors reunite China. Transportation network is developed, including Grand Canal.

Tang Dynasty (618-907) – Height of Silk Road trade. Golden age of art and learning.

Song Dynasty (907-1279) – First 50 years are marked by disorder. Age of high culture, printing, calligraphy, and poetry.

Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368) – Genghis Khan leads Mongols in attack on China, his grandson founds the Yuan Dynasty.

Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) – European traders arrive. commerce grows. Forbidden City is built, and Great Wall is extended.

Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) – Manchu invaders from the North set up this dynasty. Nationalist uprisings bring collapse.

Modern History

China has gone through startling changes in the past hundred years. China travel today provides the opportunity to learn more about the historical events that helped shape modern China.

The last Chinese dynasty ended officially in 1911, with the following years being marked by a battle for power between urban capitalist forces and Mao Zedong of the rural Chinese Communist Party.

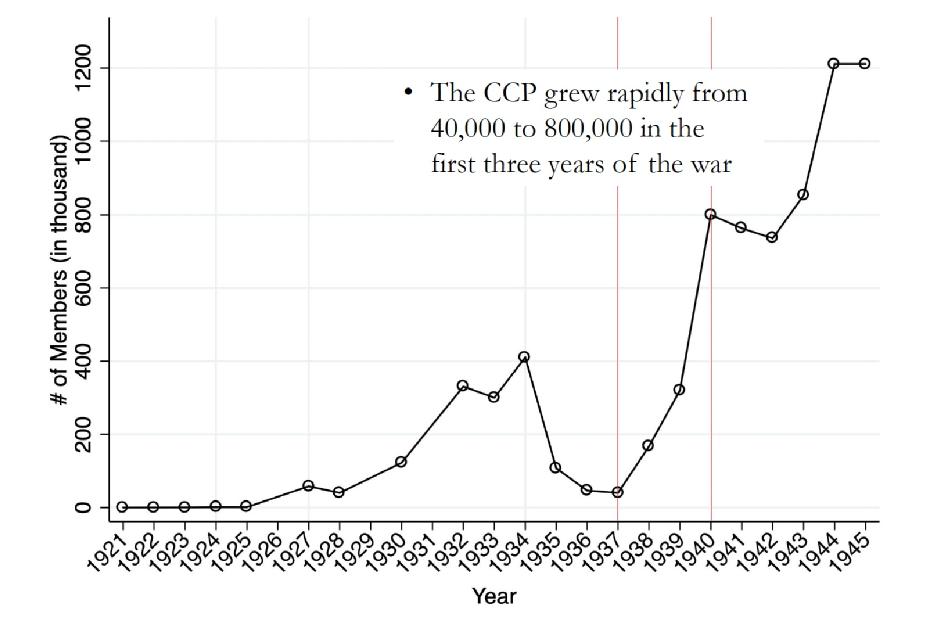

A republican China began in 1911, and due to continuing internal strife – including the development of nationalist and communist parties – China found itself vulnerable to a Japanese invasion in 1937. By 1945, 20 million Chinese had died. With the start of WWII, Japan redirected its attention toward the United States. China’s communist party then began to build up their ranks in the north in order to resume civil war after the Japanese were defeated.

After the end of WWII, China’s nationalist party struggled with debt and disorganization, and was defeated by the CCP. Thereafter, Mao Zedong announced the creation of the People’s Republic of China.

In 1958, after becoming increasingly estranged from the original financial backers in Moscow, Mao launched the Great Leap Forward. This program focused on collectivizing farms to increase crop production. The greatest man-made famine resulted, and millions of Chinese starved to death. In its recovery, China tried to position itself as a superpower. But in 1966, Mao’s promotion of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution led to the anti-authoritarian anarchy. Students were encouraged to join Red Guard units and fought government troops, and eventually fought each other for power. The revolution “officially” ending in 1969 with cessation of abuses, but in reality, it did not come to rest until the death of Mao in 1976, having accomplished little of importance.

Deng Xiaoping emerged with an economic reform program in 1978 and instilled the value of function. Propelled by events in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, unarmed demonstrators gathered in Tiananmen Square in 1989 to question political reformation and were put down with force by the CCP. This is a popular sight for China tours to include – it can be an emotional visit for many travelers. Tiananmen Square evokes a variety of passions from local people, as well.

In 1993 Deng publicly approved of economic growth efforts, and afterwards the economy exploded with rapid growth. Deng, perhaps in an effort to change the course of Chinese politics, passed power to Jiang Zemin several years before dying, which may help to establish a pattern for stable transitions between leaders in the future. Though the legacy of intellectual oppression and censorship still exists today, China’s recent leaders have embraced free trade and as such the country’s economy is on the rise due to the influx of global trade. On a China trip, travelers are able to observe how history has shaped current conditions within the country.

Politics

Many improvements have been made in an effort to establish human rights, including allowing citizens to sue officials for abuse of authority, as well as the establishment of trial procedures including rights due process. China acknowledges in principle the necessity to protect human rights and is beginning to undergo a process to bring its practices up to standards with international norms. While in its beginning stages, the initial groundwork is being laid to protect citizens from a repeat of the totalitarian rule of China’s history.

China politics are as fascinating as its traditional cultures, diverse landscape, and rare wildlife. Taking the time to learn a little bit about the country’s politics will only add to the intimacy of your China travel experiences.

Culture

People: Over one hundred ethnic groups have inhabited the country of China, many assimilating into neighboring ethnicities, disappearing altogether, or merging into the more prominent Han comprised of various smaller groups.

Language: On your China trip it is quite possible that you will hear variety in the language being spoken, as the Han speak several different dialects and languages that share a common written standard. This standard is called Vernacular Chinese and is based on Standard Mandarin, the most prominent spoken language. The People’s Republic of China now officially recognizes a total of 56 ethnic groups wrapped into this one country that is makes up 1/5 of the world’s population.

Religion: Though the Chinese government has officially classified the country as an athiest nation, supervised religions are allowed. Historically, Taoism and Buddhism are the dominant religions, with Christianity and Islam comprising less than 6% of the population when combined.

Literature: Chinese literature has been an ingrained art since the development of printmaking during the Song Dynasty. Many manuscripts of Classics and religious texts comprised of Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist were manually written by ink brush. Tens of thousands of ancient manuscripts still exist and many more are being discovered each day.

Education: The Chinese developed a meritocratic method for creating opportunity for social advancement. Anyone who could perform well on the imperial examinations, which required students to write essays and demonstrate mastery of the Confucian classics, became elite scholar-officials known as jinshi. This method largely excluded females or those too poor to prepare for the test. This theory was largely different from the European system of blood nobility. Chinese philosophers, writers, and poets in past and present have been highly respected and continue to play key roles in promoting the culture of the Chinese empire.

Calligraphy: Even before you begin your China travels, it is likely you will have had previous exposure to one of China’s highest ranking art forms—calligraphy. Calligraphy ranks even higher in China than painting or music. It holds an association with elite scholars, and after becoming commercialized, the work of a famous artist becomes very valuable.

Art & Music: The amazing variation in Chinese landscapes has inspired great works of art and Chinese paintings; during your China trip, you’ll have plenty of opportunities to visit the regions of China that have long motivated the masters. Sushi and Bonzai, also native Chinese art forms, spread later to Japan and Korea due to their popularity. The Chinese have also contributed many musical instruments, including the zheng, xiao and erhu.

The Opium Wars and the Unequal Treaty System

The Opium Wars in the mid-19th century were a critical juncture in modern Chinese history. The first Opium War was fought between China and Great Britain from 1839 to 1842. In the second Opium War, from 1856 to 1860, a weakened China fought both Great Britain and France. China lost both wars. The terms of its defeat were a bitter pill to swallow: China had to cede the territory of Hong Kong to British control, open treaty ports to trade with foreigners, and grant special rights to foreigners operating within the treaty ports. In addition, the Chinese government had to stand by as the British increased their opium sales to people in China. The British did this in the name of free trade and without regard to the consequences for the Chinese government and Chinese people.

The lesson that Chinese students learn today about the Opium Wars is that China should never again let itself become weak, ‘backward,’ and vulnerable to other countries. As one British historian says, “If you talk to many Chinese about the Opium War, a phrase you will quickly hear is ‘luo hou jiu yao ai da,’ which literally means that if you are backward, you will take a beating.”1

Two Worlds Collide: The First Opium War

In the mid-19th century, western imperial powers such as Great Britain, France, and the United States were aggressively expanding their influence around the world through their economic and military strength and by spreading religion, mostly through the activities of Christian missionaries. These countries embraced the idea of free trade, and their militaries had become so powerful that they could impose such ideas on others. In one sense, China was relatively effective in responding to this foreign encroachment; unlike its neighbours, including present-day India, Burma (now Myanmar), Malaya (now Malaysia), Indonesia, and Vietnam, China did not become a full-fledged, formal colony of the West. In addition, Confucianism, the system of beliefs that shaped and organized China’s culture, politics, and society for centuries, was secular (that is, not based on a religion or belief in a god) and therefore was not necessarily an obstacle to science and modernity in the ways that Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism sometimes were in other parts of the world.

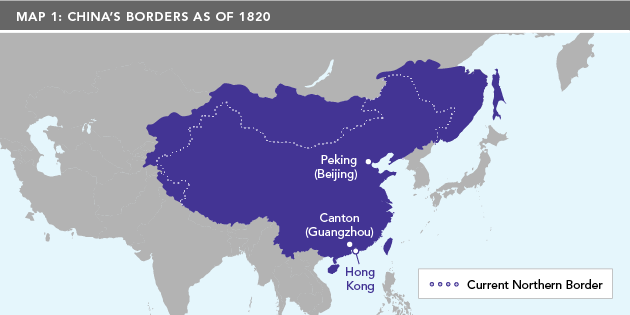

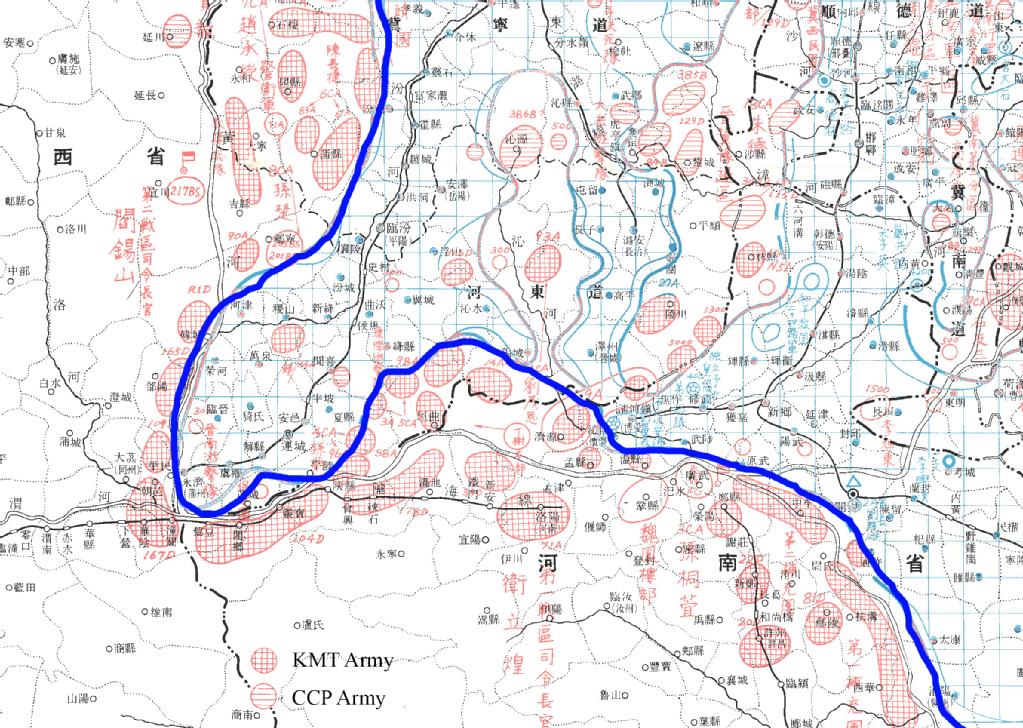

But in another sense, China was not effective in responding to the “modern” West with its growing industrialism, mercantilism, and military strength. Nineteenth-century China was a large, mostly land-based empire (see Map 1), administered by a c. 2,000-year-old bureaucracy and dominated by centuries old and conservative Confucian ideas of political, social, and economic management. All of these things made China, in some ways, dramatically different from the European powers of the day, and it struggled to deal effectively with their encroachment. This ineffectiveness resulted in, or at least added to, longer-term problems for China, such as unequal treaties (which will be described later), repeated foreign military invasions, massive internal rebellions, internal political fights, and social upheaval. While the first Opium War of 1839–42 did not cause the eventual collapse of China’s 5,000-year imperial dynastic system seven decades later, it did help shift the balance of power in Asia in favour of the West.

Map 1: China’s Borders as of 1820.

Opium and the West’s Embrace of Free Trade

In the decades leading up to the first Opium War, trade between China and the West took place within the confines of the Canton System, based in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou (also referred to as Canton). An earlier version of this system had been put in place by China under the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), and further developed by its replacement, the Qing Dynasty, also known as the Manchu Dynasty. (The Manchus were the ethnic group that ruled China during the Qing period.) In the year 1757, the Qing emperor ordered that Guangzhou/Canton would be the only Chinese port that would be opened to trade with foreigners, and that trade could take place only through licensed Chinese merchants. This effectively restricted foreign trade and subjected it to regulations imposed by the Chinese government.

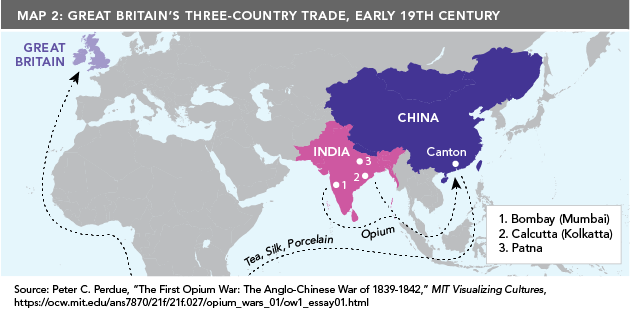

For many years, Great Britain worked within this system to run a three country trade operation: It shipped Indian cotton and British silver to China, and Chinese tea and other Chinese goods to Britain (see Map 2). In the 18th and early 19th centuries, the balance of trade was heavily in China’s favour. One major reason was that British consumers had developed a strong liking for Chinese tea, as well as other goods like porcelain and silk. But Chinese consumers had no similar preference for any goods produced in Britain. Because of this trade imbalance, Britain increasingly had to use silver to pay for its expanding purchases of Chinese goods. In the late 1700s, Britain tried to alter this balance by replacing cotton with opium, also grown in India. In economic terms, this was a success for Britain; by the 1820s, the balance of trade was reversed in Britain’s favour, and it was the Chinese who now had to pay with silver.

Map 2: Great Britain’s Three-Country Trade, Early 19th Century.

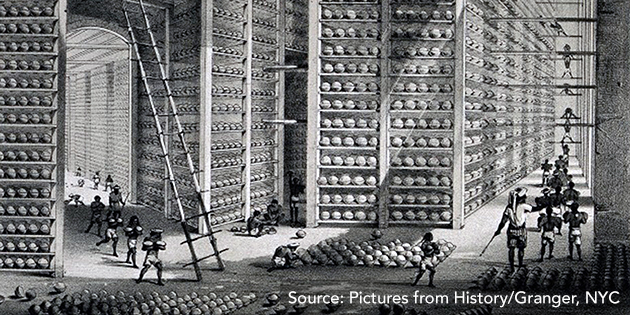

Figure 1: A “stacking room” in an opium factory in Patna, India. On the shelves are balls of opium that were part of Britain’s trade with China.

The Scourge and Profit of Opium

The opium that the British sold in China was made from the sap of poppy plants, and had been used for medicinal and sometimes recreational purposes in China and other parts of Eurasia for centuries. After the British colonized large parts of India in the 17th century, the British East India Company, which was created to take advantage of trade with East Asia and India, invested heavily in growing and processing opium, especially in the eastern Indian province of Bengal. In fact, the British developed a profitable monopoly over the cultivation of opium that would be shipped to and sold in China.

By the early 19th century, more and more Chinese were smoking British opium as a recreational drug. But for many, what started as recreation soon became a punishing addiction: many people who stopped ingesting opium suffered chills, nausea, and cramps, and sometimes died from withdrawal. Once addicted, people would often do almost anything to continue to get access to the drug. The Chinese government recognized that opium was becoming a serious social problem and, in the year 1800, it banned both the production and the importation of opium. In 1813, it went a step further by outlawing the smoking of opium and imposing a punishment of beating offenders 100 times.

Figure 2: Opium smoking in China.

In response, the British East India Company hired private British and American traders to transport the drug to China. Chinese smugglers bought the opium from British and American ships anchored off the Guangzhou coast and distributed it within China through a network of Chinese middlemen. By 1830, there were more than 100 Chinese smugglers’ boats working the opium trade.

This reached a crisis point when, in 1834, the British East India Company lost its monopoly over British opium. To compete for customers, dealers lowered their selling price, which made it easier for more people in China to buy opium, thus spreading further use and addition.

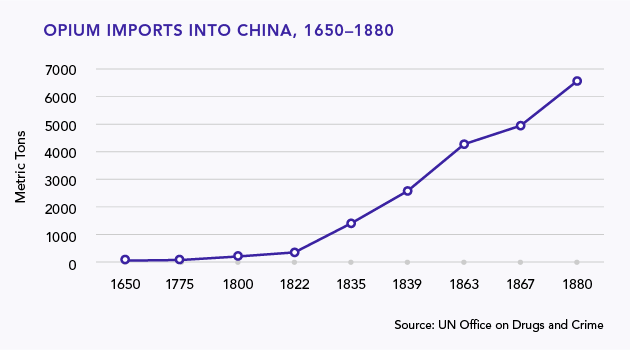

In less than 30 years—from 1810 to 1838—opium imports to China increased from 4,500 chests (the large containers used to ship the drug) to 40,000. As Chinese consumed more and more imported opium, the outflow of silver to pay for it increased, from about two million ounces in the early 1820s to over nine million ounces a decade later. In 1831, the Chinese emperor, already angry that opium traders were breaking local laws and increasing addiction and smuggling, discovered that members of his army and government (and even students) were engaged in smoking opium.

The Users Versus Pushers Debate

By 1836, the Chinese government began to get more serious about enforcing the 1813 ban. It closed opium dens and executed Chinese dealers. But the problem only grew worse. The emperor called for a debate among Chinese officials on how best to deal with the crisis. Opinion were polarized into two sides.

One side took a pragmatic approach (that is, an approach not focused on the morality of the issue). It focused on targeting opium users rather than opium producers. They argued that the production and sale of opium should be legalized and then taxed by the government. Their belief was that taxing the drug would make it so expensive that people would have to smoke less of it or not smoke it at all. They also argued that the money collected from taxing the opium trade could help the Chinese government reduce revenue shortfalls and the outflow of silver.

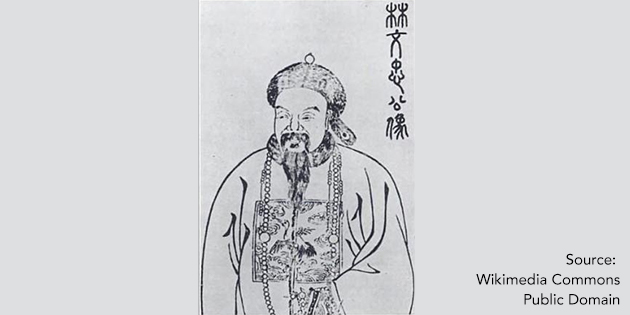

Another side vehemently disagreed with this ‘pragmatic’ approach. Led by Lin Zexu, a very capable and ambitious Chinese government official, they argued that the opium trade was a moral issue, and an “evil” that had to be eliminated by any means possible. If they could not suppress the trade of opium and addiction to it, the Chinese empire would have no peasants to work the land, no townsfolk to pay taxes, no students to study, and no soldiers to fight. They argued that instead of targeting opium users, they should stop and punish the “pushers” who imported and sold the drug in China.

Figure 3: Lin Zexu.

In the end, Lin Zexu’s side won the argument. In 1839, he arrived in Guangzhou (Canton) to supervise the ban on the opium trade and to crack down on its use. He attacked the opium trade on several levels. For example, he wrote an open letter to Queen Victoria questioning Britain’s political support for the trade and the morality of pushing drugs. More importantly, he made rapid progress in enforcing the 1813 ban by arresting over 1,600 Chinese dealers and seizing and destroying tens of thousands of opium pipes. He also demanded that foreign companies (British companies, in particular) turn over their supplies of opium in exchange for tea. When the British refused to do so, Lin stopped all foreign trade and quarantined the area to which these foreign merchants were confined.

After six weeks, the foreign merchants gave in to Lin’s demands and turned over 2.6 million pounds of opium (over 20,000 chests). Lin’s troops also seized and destroyed the opium that was being held on British ships—the British superintendent claimed these ships were in international waters, but Lin claimed they were anchored in and around Chinese islands. Lin then hired 500 Chinese men to destroy the opium by mixing it with lime and salt and dumping it into the bay. Finally, he pressured the Portuguese, who had a colony in nearby Macao, to expel the uncooperative British, forcing them to move to the island of Hong Kong.

Figure 4: British officers in their tent during the first Opium War, circa 1839.

Taken together, these actions raised the tensions that led to the outbreak of the first Opium War. For the British, Lin’s destruction of the opium was an affront to British dignity and their concepts of trade. Many British merchants, smugglers, and the British East India Company had argued for years that China was out of touch with “civilized” nations, which practised free trade and maintained “normal” international relations through consular officials and treaties. More to the point, British representatives in Guangzhou requested that merchants turn over their opium to Lin, guaranteeing that the British government would compensate them for their losses. The idea was that in the short term, this would prevent a major conflict, and that it would keep the merchants and ship captains safe while reopening the extremely profitable China trade in other goods. The huge opium liability (the opium was worth millions of pounds sterling), and increasingly shrill demands from merchants in China, India, and London when they discovered their profits were destroyed, gave politicians in Great Britain the excuse they were looking for to act more forcefully to expand British imperial interests in China. War broke out in November 1839 when Chinese warships clashed with British merchantmen.

Figure 5: Chinese swordsman, 1844.

In June 1840, 16 British warships and merchantmen—many leased from the primary British opium producer, Jardine Matheson & Co.—arrived at Guangzhou. Over the next two years, the British forces bombarded forts, fought battles, seized cities, and attempted negotiations. A preliminary settlement called for China to cede Hong Kong to the British Empire, pay an indemnity, and grant Britain full diplomatic relations. It also led to the Qing government sending Lin Zexu into exile. Chinese troops, using antiquated guns and cannons, and with limited naval ships, were largely ineffective against the British. Dozens of Chinese officers committed suicide when they could not repel the British marines, steamships, and merchantmen.

Figure 6: The British bombardment of Guangzhou/Canton.

The War’s Aftermath

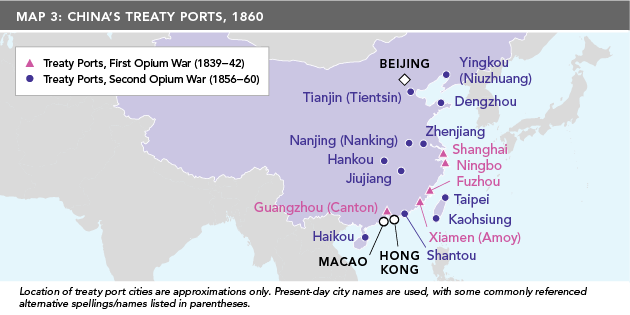

The first Opium War ended in 1842, when Chinese officials signed, at gunpoint, the Treaty of Nanjing. The treaty provided extraordinary benefits to the British, including:

- an excellent deep-water port at Hong Kong;

- a huge indemnity (compensation) to be paid to the British government and merchants;

- five new Chinese treaty ports at Guangzhou (Canton), Shanghai, Xiamen (Amoy), Ningbo, and Fuzhou, where British merchants and their families could reside;

- extraterritoriality for British citizens residing in these treaty ports, meaning that they were subject to British, not Chinese, laws; and

- a “most favoured nation” clause that any rights gained by other foreign countries would automatically apply to Great Britain as well.

For China, the Treaty of Nanjing provided no benefits. In fact, Chinese imports of opium rose to a peak of 87,000 chests in 1879 (see Figure 1). After that, imports of opium declined, and then ended during the First World War, as opium production within China outgrew foreign production. However, other trade did not expand as much as foreign merchants had hoped, and they continued to blame the Chinese government for this. Among Chinese officials, the aftermath of the war led to a bitter political struggle between two factions: a peace faction, which was roughly aligned with the ‘users’ faction in the opium trade debate; and a ‘war’ faction, which was roughly aligned with the ‘pushers’ faction in that debate. The peace faction was in nominal control.

Figure 7: Opium War Imports into China, 1650-1880.

Figure 7: Opium War Imports into China, 1650-1880.

In addition, the Treaty of Nanjing ended the Canton System that had been in place since the 17th century. This was followed in 1844 by a system of unequal treaties between China and western powers. Through the most favoured nation clauses, these treaties allowed westerners to build churches and spread Christianity in the treaty ports. Western imperialism and free trade had its first great victory in China with this war and its resulting treaties.

When the Chinese emperor died in 1850, his successor dismissed the peace faction in favour of those who had supported Lin Zexu. The new emperor tried to bring Lin back from exile, but Lin died along the way. The Chinese court kept finding excuses not to accept foreign diplomats at the capital city of Beijing, and its compliance with the treaties fell far short of western countries’ expectations.

Second Opium War (1856–1860)

In 1856, a second Opium War broke out and continued until 1860, when the British and French captured Beijing and forced on China a new round of unequal treaties, indemnities, and the opening of 11 more treaty ports (see Map 3). This also led to increased Christian missionary work and legalization of the opium trade.

Map 3: China’s Treaty Ports, 1860.

Even though new ports were opened to British merchants after the first Opium War, the Chinese dragged their feet on implementing the agreements, and legal trade with China remained limited. British merchants pressed their government to do more, but the government’s hands were tied because the Chinese government in the capital city of Beijing restricted who it met with.

In October 1856, Chinese authorities arrested the Chinese crew of a ship operated by the British. The British used this as an opportunity to pressure China militarily to open itself up even further to British merchants and trade. France, using the execution in China of a French Christian missionary as an excuse, joined the British in the fight. Joint French-British forces captured Guangzhou before moving north to the city of Tianjin (also referred to as Tientsin). In 1858, the Chinese agreed—on paper—to a series of western demands contained in documents like the Treaty of Tientsin. But then they refused to ratify the treaties, which led to further hostilities.

In 1860, British and French troops landed near Beijing and fought their way into the city. Negotiations quickly broke down and the British High Commissioner to China ordered the troops to loot and destroy the Imperial Summer Palace, a complex and garden where Qing Dynasty emperors had traditionally handled the country’s official matters.

Shortly after that, the Chinese emperor fled to Manchuria in northeast China. His brother negotiated the Convention of Beijing, which, in addition to ratifying the Treaty of Tientsin, added indemnities and ceded to Britain the Kowloon Peninsula across the strait from Hong Kong. The war ended with a greatly weakened Qing Dynasty that was now confronted with the need to rethink its relations with the outside world and to modernize its military, political, and economic structures.

Thinking About the Opium War

In 1839, the British imposed on China their version of free trade and insisted on the legal right of their citizens (that is, British citizens) to do what they wanted, wherever they wanted. Chinese critics point out that while the British made lofty arguments about the ‘principle’ of free trade and individual rights, they were in fact pushing a product (opium) that was illegal in their own country.

There are different viewpoints on what was the main underlying factor in Britain’s involvement in the Opium Wars. Some in the west claim that the Opium Wars were about upholding the principle of free trade. Others, however, say that Great Britain was acting more in the interest of protecting its international reputation while it was facing challenges in other parts of the world, such as the Near East, India, and Latin America. Some American historians have argued that these conflicts were not so much about opium as they were about western powers’ desire to expand commercial relations more broadly and to do away with the Canton trading system. Finally, some western historians say the war was fought at least partly to keep China’s balance of trade in a deficit, and that opium was an effective way to do that, even though it had very negative impacts on Chinese society.

It is important to point out that not everyone in Britain supported the opium trade in China. In fact, members of the British public and media, as well as the American public and media, expressed outrage over their countries’ support for the opium trade.2

From China’s historical perspective, the first Opium War was the beginning of the end of late Imperial China, a powerful dynastic system and advanced civilization that had lasted thousands of years. The war was also the first salvo in what is now referred to in China as the “century of humiliation.” This humiliation took many forms. China’s defeat in both wars was a sign that the Chinese state’s legitimacy and ability to project power were weakening. The Opium Wars further contributed to this weakening. The unequal treaties that western powers imposed on China undermined the ways China had conducted relations with other countries and its trade in tea. The continuation of the opium trade, moreover, added to the cost to China in both silver and in the serious social consequences of opium addiction. Furthermore, the many rebellions that broke out within China after the first Opium War made it increasingly difficult for the Chinese government to pay its tax and huge indemnity obligations.

Present-day Chinese historians see the Opium Wars as a wars of aggression that led to the hard lesson that “if you are ‘backward,’ you will take a beating.” These lessons shaped the rationale for the Chinese Revolution against imperialism and feudalism that emerged, and then succeeded, decades later.

The Unequal Treaty

Unequal treaty is the name given by the Chinese to a series of treaties signed during the 19th and early 20th centuries, between China, (mostly referring to the Qing dynasty) various Western powers (specifically the United Kingdom, France, Germany, the United States, Russia), and also with Japan. The agreements, often reached after a military defeat or a threat of military invasion, contained one-sided terms, requiring China to cede land, pay reparations, open treaty ports, give up tariff autonomy, legalise opium import, and grant extraterritorial privileges to foreign citizens.

With the rise of Chinese nationalism and anti-imperialism in the 1920s, both the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party used the concept to characterize the Chinese experience of losing sovereignty between roughly 1840 to 1950. The term “unequal treaty” became associated with the concept of China’s “century of humiliation”, especially the concessions to foreign powers and the loss of tariff autonomy through treaty ports, although Qing China and Korea also signed treaties like the China–Korea Treaty of 1882 which granted similar privileges to China.

Japanese and Koreans also use the term to refer to several treaties that resulted in the loss of their sovereignty, to varying degrees.

China

In China, the term “unequal treaty” first came into use in the early 1920s to describe the historical treaties, still imposed on the then-Republic of China, that were signed through the period of time which the American sinologist John K. Fairbank characterized as the “treaty century” which began in the 1840s.

In assessing the term’s usage in rhetorical discourse since the early 20th century, American historian Dong Wang notes that “while the phrase has long been widely used, it nevertheless lacks a clear and unambiguous meaning” and that there is “no agreement about the actual number of treaties signed between China and foreign countries that should be counted as unequal.” However, within the scope of Chinese historiographical scholarship, the phrase has typically been defined to refer to the many cases in which China was effectively forced to pay large amounts of financial reparations, open up ports for trade, cede or lease territories (such as Outer Manchuria and Outer Northwest China (including Zhetysu) to the Russian Empire, Hong Kong and Weihaiwei to the United Kingdom, Guangzhouwan to France, Kwantung Leased Territory and Taiwan to the Empire of Japan, the Jiaozhou Bay concession to the German Empire and concession territory in Tientsin, Shamian, Hankou, Shanghai etc.), and make various other concessions of sovereignty to foreign spheres of influence, following military threats.

The Chinese-American sinologist Immanuel Hsu states that the Chinese viewed the treaties they signed with Western powers and Russia as unequal “because they were not negotiated by nations treating each other as equals but were imposed on China after a war, and because they encroached upon China’s sovereign rights … which reduced her to semicolonial status”.

The earliest treaty later referred to as “unequal” was the 1841 Convention of Chuenpi negotiations during the First Opium War. The first treaty between China and the United Kingdom termed “unequal” was the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842.

Following Qing China’s defeat, treaties with Britain opened up five ports to foreign trade, while also allowing foreign missionaries, at least in theory, to reside within China. Foreign residents in the port cities were afforded trials by their own consular authorities rather than the Chinese legal system, a concept termed extraterritoriality. Under the treaties, the UK and the US established the British Supreme Court for China and Japan and United States Court for China in Shanghai.

Chinese post-World War I resentment

After World War I, patriotic consciousness in China focused on the treaties, which now became widely known as “unequal treaties.” The Nationalist Party and the Communist Party competed to convince the public that their approach would be more effective. Germany was forced to terminate its rights, the Soviet Union surrendered them, and the United States organized the Washington Conference to negotiate them.

After Chiang Kai-shek declared a new national government in 1927, the Western powers quickly offered diplomatic recognition, arousing anxiety in Japan. The new government declared to the Great Powers that China had been exploited for decades under unequal treaties, and that the time for such treaties was over, demanding they renegotiate all of them on equal terms.

Towards the end of the unequal treaties

After the Boxer Rebellion and the signing of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902, Germany began to reassess its policy approach towards China. In 1907 Germany suggested a trilateral German-Chinese-American agreement that never materialised. Thus China entered the new era of ending unequal treaties on March 14, 1917 when it broke off diplomatic relations with Germany, thereby terminating the concessions it had given that country, with China declaring war on Germany on August 17, 1917.

As World War I commenced, these acts voided the unequal treaty of 1861, resulting in the reinstatement of Chinese control on the concessions of Tianjin and Hankou to China. In 1919, the post-war peace negotiations failed to return the territories in Shandong, previously under German colonial control, back to the Republic of China. After it was determined that the Japanese forces occupying those territories since 1914 would be allowed to retain them under the Treaty of Versailles, the Chinese delegate Wellington Koo refused to sign the peace agreement, with China being the only conference member to boycott the signing ceremony. Widely perceived in China as a betrayal of the country’s wartime contributions by the other conference members, the domestic backlash following the failure to restore Shandong would cause the collapse of the cabinet of the Duan Qirui government and lead to the May 4th movement.

On May 20, 1921, China secured with the German-Chinese peace treaty (Deutsch-chinesischer Vertrag zur Wiederherstellung des Friedenszustandes) a diplomatic accord which was considered the first equal treaty between China and a European nation.

Many of the other treaties China considers unequal were repealed during the Second Sino-Japanese War, which started in 1937 and merged into the larger context of World War II. Entering the war with the Attack on Pearl Harbor, China became a major ally in the war effort and the United States Congress was pressed to end American extraterritoriality in December 1943. Significant examples outlasted World War II: treaties regarding Hong Kong remained in place until Hong Kong’s 1997 handover, though in 1969, to improve Sino-Soviet relations in the wake of military skirmishes along their border, the People’s Republic of China was forced to reconfirm the 1858 Treaty of Aigun and 1860 Treaty of Peking.

Japan

When the US expeditionary fleet led by Matthew Perry reached Japan in 1854 to force open the island nation for American trade, the country was compelled to sign the Convention of Kanagawa under the threat of violence by the American warships. Although its historical importance has been argued by some to be limited, this event abruptly terminated Japan’s 220 years of seclusion under the Sakoku policy of 1633 under unilateral foreign pressure and consequentially, the convention has been seen in a similar light as an unequal treaty.

Another significant incident was the Tokugawa Shogunate’s capitulation to the Harris Treaty of 1858, negotiated by the eponymous U.S. envoy Townsend Harris, which, among other concessions, established a system of extraterritoriality for foreign residents. This agreement would then serve as a model for similar treaties to be further signed by Japan with other foreign Western powers in the weeks to follow.

The enforcement of these unequal treaties were a tremendous national shock for Japan’s leadership as they both curtailed Japanese sovereignty for the first time in its history and also revealed the nation’s growing weakness relative to the West through the latter’s successful imposition of such agreements upon the island nation. An objective towards the recovery of national status and strength would become an overarching priority for Japan, with the treaty’s domestic consequences being the end of the Bakufu, the 700 years of shogunate rule over Japan, and the establishment of a new imperial government.

The unequal treaties ended at various times for the countries involved and Japan’s victories in the 1894–95 First Sino-Japanese War convinced many in the West that unequal treaties could no longer be enforced on Japan.

Korea

Korea’s first unequal treaty was not with the West, but instead with Japan. The Ganghwa Island incident in 1875 saw Japan send the warship Un’yō led by Captain Inoue Yoshika with the implied threat of military action to coerce the Korean kingdom of Joseon through the show of force. After an armed clash ensued around Ganghwa Island where the Japanese force was sent, which resulted in its victory, the incident subsequently forced Korea to open its doors to Japan by signing the Treaty of Ganghwa Island, also known as the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876.

During this period Korea also signed treaties with Qing China and the West powers (such as the United Kingdom and the United States). In the case of Qing China, it signed the China–Korea Treaty of 1882 with Korea stipulating that Korea was a dependency of China and granted the Chinese extraterritoriality and other privileges, and in subsequent treaties China also obtained concessions in Korea, notably the Chinese concession of Incheon. However, Qing China lost its influence over Korea following the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895.

As Japanese dominance over the Korean peninsula grew in the following decades, with respect to the unequal treaties imposed upon the kingdom by the West powers, Korea’s diplomatic concessions with those states became largely null and void in 1910, when it was annexed by Japan.

Taiping Rebellion

The Taiping Rebellion (1851-1864) was a millenarian uprising in southern China that began as a peasant rebellion and turned into an extremely bloody civil war. It broke out in 1851, a Han Chinese reaction against the Qing Dynasty, which was ethnically Manchu. The rebellion was sparked by a famine in Guangxi Province, and Qing government repression of the resulting peasant protests.

A would-be scholar named Hong Xiuquan, from the Hakka minority, had tried for years to pass the exacting imperial civil service examinations but had failed each time. While suffering from a fever, Hong learned from a vision that he was the younger brother of Jesus Christ and that he had a mission to rid China of Manchu rule and of Confucian ideas. Hong was influenced by an eccentric Baptist missionary from the United States named Issachar Jacox Roberts.

Hong Xiuquan’s teachings and the famine sparked a January 1851 uprising in Jintian (now called Guiping), which the government quashed. In response, a rebel army of 10,000 men and women marched to Jintian and overran the garrison of Qing troops stationed there; this marks the official start of the Taiping Rebellion.

Taiping Heavenly Kingdom

To celebrate the victory, Hong Xiuquan announced the formation of the “Taiping Heavenly Kingdom,” with himself as king. His followers tied red cloths around their heads. The men also grew out their hair, which had been kept in the queue style as per Qing regulations. Growing long hair was a capital offense under Qing law.

The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom had other policies that put it at odds with Beijing. It abolished private ownership of property, in an interesting foreshadowing of Mao’s communist ideology. Also, like the communists, the Taiping Kingdom declared men and women equal and abolished social classes. However, based on Hong’s understanding of Christianity, men and women were kept strictly segregated, and even married couples were prohibited from living together or having sex. This restriction did not apply to Hong himself, of course–as self-proclaimed king, he had a large number of concubines.

The Heavenly Kingdom also outlawed foot binding, based its civil service exams on the Bible instead of Confucian texts, used a lunar calendar rather than a solar one, and outlawed vices such as opium, tobacco, alcohol, gambling, and prostitution.

The Rebels

The Taiping rebels’ early military success made them quite popular with the peasants of Guangxi, but their efforts to attract support from the middle-class landowners and from Europeans failed. The leadership of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom began to fracture, as well, and Hong Xiuquan went into seclusion. He issued proclamations, mostly of a religious nature, while the Machiavellian rebel general Yang Xiuqing took over military and political operations for the rebellion. Hong Xiuquan’s followers rose up against Yang in 1856, killing him, his family, and the rebel soldiers loyal to him.

The Taiping Rebellion began to fail in 1861 when the rebels proved unable to take Shanghai. A coalition of Qing troops and Chinese soldiers under European officers defended the city, then set out to crush the rebellion in the southern provinces. After three years of bloody fighting, the Qing government had retaken most of the rebel areas. Hong Xiuquan died of food poisoning in June of 1864, leaving his hapless 15-year-old son on the throne. The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom’s capital at Nanjing fell the following month after hard urban fighting, and the Qing troops executed the rebel leaders.

At its peak, the Taiping Heavenly Army likely fielded approximately 500,000 soldiers, male and female. It initiated the idea of “total war” – every citizen living within the boundaries of the Heavenly Kingdom was trained to fight, thus civilians on either side could expect no mercy from the opposing army. Both opponents used scorched earth tactics, as well as mass executions. As a result, the Taiping Rebellion was likely the bloodiest war of the nineteenth century, with an estimated 20 – 30 million casualties, mostly civilians. Around 600 entire cities in Guangxi, Anhui, Nanjing, and Guangdong Provinces were wiped from the map.

Despite this horrific outcome, and the founder’s millennial Christian inspiration, the Taiping Rebellion proved motivational for Mao Zedong’s Red Army during the Chinese Civil War the following century. The Jintian Uprising that started it all has a prominent place on the “Monument to the People’s Heroes” that stands today in Tiananmen Square, central Beijing.

Boxer Rebellion

In the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, a Chinese secret organization called the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists led an uprising in northern China against the spread of Western and Japanese influence there. The rebels, referred to by Westerners as Boxers because they performed physical exercises they believed would make them able to withstand bullets, killed foreigners and Chinese Christians and destroyed foreign property.

From June to August, the Boxers besieged the foreign district of China’s capital city Beijing (then called Peking) until an international force that included American troops subdued the uprising. By the terms of the Boxer Protocol, which officially ended the rebellion in 1901, China agreed to pay more than $330 million in reparations.

Cause of the Boxer Rebellion

By the end of the 19th century, Western nations and Japan had forced China’s ruling Qing dynasty to accept wide foreign control over the country’s economic affairs. Throughout the Opium Wars of 1839-42 and 1856-60, popular rebellions and the Sino-Japanese War, China had fought to resist the foreigners, but it lacked a modernized military and suffered millions of casualties.

America returned the money it received from China after the Boxer Rebellion, on the condition it be used to fund the creation of a university in Beijing. Other nations involved later remitted their shares of the Boxer indemnity as well.

John Hay, the U.S. Secretary of State from 1898 to 1905, began to implement an “Open Door Policy” to exert American and European influence over Chinese trade and economic partnerships. Though his Open Door Policy was met with indifference or resistance by other players—including the Qing Empress Dowager Tzu’u Hzi—continued Western influence over domestic Chinese affairs set the stage for rebellion.

By the late 1890s, a Chinese secret group, the Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists (“I-ho-ch’uan” or “Yihequan”), had begun carrying out regular attacks on foreigners and Chinese Christians. The rebels performed calisthenics rituals and martial arts that they believed would give them the ability to withstand bullets and other forms of attack. Westerners referred to these rituals as shadow boxing, leading to the Boxers nickname.

Although the Boxers came from various parts of society, many were peasants, particularly from Shandong province, which had been struck by natural disasters such as famine and flooding. In the 1890s, China had given territorial and commercial concessions in this area to several European nations, and the Boxers blamed their poor standard of living on foreigners who were colonizing their country.

The Boxer Movement

In 1900, the Boxer movement spread to the Beijing area, where the Boxers killed Chinese Christians and Christian missionaries and destroyed churches, railroad stations and other property. On June 20, 1900, the Boxers began a siege of Beijing’s Legation District (where the official quarters of foreign diplomats were located). The following day, Empress Dowager Tzu’u Hzi declared a war on all foreign nations with diplomatic ties in China.

As the Western powers and Japan organized a multinational force to crush the rebellion, the siege stretched into weeks, and the diplomats, their families and guards suffered through hunger and degrading conditions as they fought to keep the Boxers at bay.

By some estimates, several hundred foreigners and several thousand Chinese Christians were killed during this time. On August 14, after fighting its way through northern China, an international force of approximately 20,000 troops from eight nations (Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States) arrived to take Beijing and rescue the foreigners and Chinese Christians.

Aftermath

The Boxer Rebellion formally ended with the signing of the Boxer Protocol on September 7, 1901. By terms of the agreement, forts protecting Beijing were to be destroyed, Boxer and Chinese government officials involved in the uprising were to be punished, foreign legations were permitted to station troops in Beijing for their defense, China was prohibited from importing arms for two years and it agreed to pay more than $330 million in reparations to the foreign nations involved.

The Qing dynasty, established in 1644, was weakened by the Boxer Rebellion. Following an uprising in 1911, the dynasty came to an end and China became a republic in 1912.

Unit II

Qing Restoration and Modernization Movements

Self Strengthening

The Self-Strengthening Movement was a 19th-century push to modernise China, particularly in the fields of industry and defence. Foreign imperialism in China, its defeat in the Second Opium War (1860), the humiliating Treaty of Tientsin and the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864) all exposed the dynasty’s military and technological backwardness, particularly in comparison to European nations. These disasters triggered the rise of the Self-Strengthening Movement. The advocates of Self-Strengthening were not republican radicals or social reformers. They hoped to strengthen the nation by preserving Qing rule and maintaining traditional Confucian values while embracing Western military and industrial practices. As one writer explained, it was necessary to “learn barbarian [Western] methods to combat barbarian threats”. To acquire this knowledge China had to actively engage with Western nations, examine their trade and technology, encourage the study of Western languages and develop a diplomatic service to connect with foreign governments.

The sponsors of Self-Strengthening tended to be provincial leaders, who initiated projects and reforms that benefited their region. Two examples were Zeng Guofan and Zuo Zongtang, Qing military leaders who oversaw developments in ship-building and armaments production in Shanghai and Fuzhou respectively. But the most prominent and successful advocate of Self-Strengthening was Li Hongzhang, a Qing general who was more interested in the West than most of his kind. Li organised the formation and development of Western-style military academies, the construction of fortifications around Chinese ports and the overhaul of China’s northern fleet. He later oversaw the development of capitalist enterprises, funded by private business interest but with some government involvement or oversight. Some of these projects included railways, shipping infrastructure, coal mines, cloth mills and the installation of telegraph lines and stations. From the 1880s Li was also instrumental in developing a Chinese foreign policy and forging a stable and productive relationship with Western nations.

“The educated reform faction joined the Self-Strengthening Movement with the motto ‘Confucian ethics, Western science’. China, these reformers said, could acquire modern technology, and the scientific knowledge underlying it, without sacrificing the ethical superiority of its Confucian tradition. As one of their leaders stated: ‘What we have to learn from the barbarians is only one thing: solid ships and effective guns’.”

Valerie Hansen, historian

Despite their efforts, the three-decade-long Self-Strengthening Movement was generally unsuccessful. Significant figures in the Qing government were sceptical about the movement and gave it inadequate attention or resources. Xenophobes in the bureaucracy wanted nothing to do with Western methods, so some whipped up opposition to Self-Strengthening. Another significant factor in the failure of Self-Strengthening was China’s decentralised government and the weak authority of the Qing in some regions. The majority of successful Self-Strengthening projects were managed and funded by provincial governments or private business interests. A consequence of this was that new military developments – reformed armies, military installations, munitions plants, naval vessels and so on – were often loyal to, if not controlled provincial interests. This provincialism provided little or no benefit to the Qing regime or the national interest. It also contributed to disunity and warlordism after 1916, as local warlords seized control of these military assets. Most importantly, the Self-Strengthening Movement operated on the flawed premise that economic and military modernisation could be achieved without significant political or social reform.

China incurred two more costly defeats in the late 19th century (to France in 1884-85 and Japan in 1894-95). These defeats were clear evidence the Self-Strengthening Movement had failed. Defeat at the hands of Japan, a smaller Asian nation, was particularly rankling and intensified calls for change. Many wanted to learn from the victorious Japanese. Only 40 years before, Japan was an island nation of daimyo, samurai and peasant farmers, a feudal society with a medieval subsistence economy. Yet just two generations after opening its doors to the West, Japan had been radically transformed. By the 1890s the Japanese had a constitutional monarchy with an industrial economy and the strongest military in Asia. Few Chinese leaders could deny the remarkable progress in Japan – or the need for reform and modernisation in their own country. But there was considerable disagreement about how this reform should be managed, who should direct it and how far it should go. Several Chinese political clubs were formed to debate models and approaches to reform. Writers and scholars considered whether China should mimic the Meiji reforms in Japan or find its own path to modernisation. Even the Dowager Empress Cixi was herself not opposed to economic reform, though she was certainly wary of its consequences.

1. The Self-Strengthening Movement was a campaign for economic and military reform in China, inspired by the nation’s military weakness in the mid 19th century.

2. The Self-Strengthening Movement began in the 1860s and sought to acquire and utilise Western methods. “Learn barbarian methods to combat barbarian threats” was one of its mottos.

3. The movement produced some successful capitalist and military reforms, though most of these were provincially rather than nationally based. It failed to strengthen Qing rule or military power, as suggested by subsequent defeats in two wars.

4. Self-Strengthening failed due to a lack of Qing support, the decentralised nature of government and its narrow focus. Qing leaders wanted military and economic modernisation but without accompanying social or political reforms.

5. In contrast, sweeping reforms under the Meiji Emperor had transformed Japan – once as backward as China – into a modern military-industrial state, the most advanced in Asia.

Hundred Days Reform

The Hundred Days of Reform was an attempt to modernise China by reforming its government, economy and society. These reforms were launched by the young Guangxu emperor and his followers in June 1898. The need for urgent reforms in China followed the failure of the Self Strengthening Movement and defeat in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95. Some intellectuals believed that for significant reform to succeed, it had to come from above. They hoped the young Qing emperor might follow the example of the reform-minded Meiji emperor, who had overseen and encouraged successful economic and military reforms in Japan. But the Hundred Days of Reform was short lived and mostly ineffective, thwarted by the actions of Dowager Empress Cixi and a cohort of conservatives in the Qing government and military. The failure of these reforms is considered a significant starting point for the Chinese Revolution.

The Guangxu Emperor (1871-1908) came to the throne as a four-year-old in 1875, at the height of the Self Strengthening Movement. During the emperor’s childhood matters of policy were dealt with by his aunt, adoptive mother and regent, the Dowager Empress Cixi. Historical accounts suggest the young Guangxu Emperor was reserved, shy and softly spoken – but he was also intelligent and curious. Though schooled in traditional Confucian values of caution, conservatism and respect for tradition, the young emperor developed a growing interest in the progress of other nations, as well as the fate of his own. Like others of the time, he was concerned that China had been overtaken by Japan, an island nation once considered China’s ‘younger brother’. Foreign imperialism also jeopardised China’s sovereignty and the existence of the Qing government. The Guangxu Emperor came to believe that both his dynasty and his country may not survive without significant reform.

One significant figure who shaped the emperor’s views was a young writer named Kang Youwei. Kang was no radical republican: he was a neo-Confucianist who was loyal to the emperor and the Qing dynasty. But Kang was also acutely aware of the dangers that confronted China. In the 1890s Kang published literature that offered a new interpretation of Confucianism. He suggesting it was not only about conserving the status quo but could also be an agent for progress and reform. Beginning in 1890, Kang submitted several memorials to the Guangxu emperor, urging him to consider political and social reforms. These had little impact until January 1898 when Kang Youwei was admitted to the Forbidden City, apparently at the behest of Weng Tonghe, one of the Guangxu Emperor’s tutors. There is some historiographical debate about whether Kang Youwei changed the emperor’s views or simply reinforced them. Whatever the case, Kang was certainly consulted about reform and invited to submit a package of detailed proposals. Kang’s proposed reforms, submitted to the emperor in May 1898, were quite radical. They called not just for superficial changes but a fundamental constitutional overhaul – including the destruction and replacement of government ministries and bureaucracies. In his May 1898 memorial Kang told the emperor:

“Our present trouble lies in our clinging to old institutions without knowing how to change… Nowadays the court has been undertaking some reforms, but the action of the emperor is obstructed by the ministers, and the recommendations of the able scholars are attacked by old-fashioned bureaucrats. If the charge is not “using barbarian ways to change China” then it is “upsetting the ancestral institutions.” Rumours and scandals are rampant, and people fight each other like fire and water. To reform in this way is as ineffective as attempting a forward march by walking backwards. It will inevitably result in failure. Your Majesty knows that under the present circumstances reforms are imperative and old institutions must be abolished.”

Kang’s proposal went on to detail some specific reforms: the drafting and adoption of a constitution, the creation of a national parliament, a review of the imperial examination system and sweeping changes to provincial government and the bureaucracy. In mid-June 1898, the Guangxu emperor gave an audience where he unveiled dozens of broadly-worded edicts, each ordering the reform of a particular branch of government or policy: from the military to money, from education to trade. Over the following 100 days, the emperor issued even more reform edicts, more than 180 altogether. The English language newspaper The Peking Press gave point-form summaries of these reform edicts as they were handed down. The emperor also summoned ministers, generals and officials to the Forbidden City, to receive his edicts and to discuss how reform might be developed and implemented within their respective departments.

As might be expected, many conservatives viewed these sweeping reforms as rushed, panicked and dangerous. The Guangxu Emperor’s decrees outraged traditionalist Confucian scholars, who considered them impetuous and believed they tried to do too much too soon. The reforms also threatened the position of powerful ministers and bureaucrats and created much work and disruption for others. The response was a widespread but potent campaign of whispers and intrigues against the Guangxu emperor. Much of this talk focused on the likely response of the Dowager Empress. Would she move to quash the emperor’s ambitious reforms and perhaps force his abdication? Or if she chose not to act, would the emperor be replaced by a coup d’etat orchestrated by conservative military leaders?

“Some historians said that if the emperor had implemented his changes one at a time, allowing the reactions to flare up and cool down, rather than bombarding the country with reforms, the history of China might have been different. Russian rulers have always taken the approach that one cannot cross a chasm by small steps, and they have wrenched their country out of medieval obscurity through sweeping reforms. But then they did not have an empress dowager at the helm.”

X. L. Woo, historian

In the end, both things occurred. Within days of the first edicts, Cixi was working to thwart the emperor and his reforms. The Dowager Empress ordered the removal of Weng Tonghe, the emperor’s closest advisor and strongest ally, from the Forbidden City. She ordered the appointment of Ronglu, one of her allies, as war minister and commander of the army protecting Beijing; and recruited the support of Yuan Shikai, another powerful general. Cixi now had the tools to remove the emperor – but like a skilled chess player, she waited, allowing the emperor’s own actions to justify her response. The trigger came in September when the Guangxu emperor appointed two foreigners – one English, one Japanese – to his advisory council. Fearing a Qing government influenced or even controlled by foreigners, conservatives urged Cixi to move. She did so on September 21st, entering the emperor’s residence and ordering he sign a document abdicating state power in her favour. Isolated and opposed by conservative military commanders, the young emperor had little choice but to agree.

Shortly after, Yuan Shikai led troops into the Forbidden City and placed the emperor under house arrest. The gates of Beijing were locked as the army hunted down reformists and their supporters. Dozens were captured and executed or thrown into prison; the more fortunate sought refuge in embassies or escaped to exile. Kang Youwei, who had become the figurehead of the reform movement, managed to evade capture and fled to Japan. He was later sentenced in absentia to the notorious ling chi (‘slow slicing’ or ‘death by a thousand cuts’). Within days of regaining power Cixi repealed most of the emperor’s edicts of June-September, allowing some of his milder or less significant reforms to proceed. The imperial examinations were restored, as were several positions and departments abolished by the emperor’s decrees. Newspapers which had actively supported the reforms were shut down. Scholars and writers were ordered to cease submitting memorials on political matters unless they held a government position that entitled them to do so.

The suppression of the Hundred Days reforms surprised few in China. The Western press, which had given only passing attention to the reforms, seethed with indignation about the emperor’s betrayal. One newspaper in Boston, United States described the restoration of Cixi’s authority as “returning darkness” and “a lapse to barbarism in that country”. Many historians have since echoed this position, suggesting the failure of the reforms was a sign of the Qing regime’s unwillingness and inability to adapt and progress. Others have taken a more nuanced view, arguing the reforms failed because they abandoned gradualism, attempted too much in too narrow a timeframe and were unacceptable for the conservative Qing bureaucracy and military. The Guangxu Emperor’s reforms may have failed at large, however, some were permitted to proceed or were adopted later. Beijing University, formed in an edict of July 3rd, continued and became an important source of revolutionary ideas and activity. Some political and educational reforms annulled by Cixi in 1898 were adopted during the last decade of the regime.

1. The Hundred Days of Reform was an attempt by the Guangxu Emperor and his supporters, particularly the writer Kang Youwei, to force rapid modernisation on Chinese government and society.

2. This urgency for reform followed the failure of the Self Strengthening Movement and China’s 1895 defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War.

3. Between June and September 1898 the Guangxu Emperor issued more than 180 reformist edicts, making sweeping changes in areas including government, the bureaucracy, education and the military.

4. The dimensions and the pace of these reforms angered and threatened conservative ministers, bureaucrats and military officers. Some of them lobbied for action from Dowager Empress Cixi.

5. On September 21st, Cixi acted. Backed by conservative military leaders, she forced the emperor to abdicate all state power in her favour. The emperor was held under house arrest and most of his reforms were either abolished and wound back.

Expansion of Foreign Powers and "Scramble for Concessions"

The expansion of foreign powers in China has a complex and multifaceted history, marked by periods of imperialistic endeavors, colonization, and spheres of influence. This narrative spans several centuries, involving Western powers, Japan, and other foreign actors. The interactions were shaped by economic interests, geopolitical rivalries, and the broader context of global power dynamics. Here’s a detailed exploration of the expansion of foreign powers in China:

Early Contacts and Trade (Pre-19th Century):

1. Silk Road and Early Trade:

- China has a long history of trade along the Silk Road, connecting it with various cultures and civilizations. Chinese goods such as silk and porcelain were highly sought after.

2. Mongol Rule and Yuan Dynasty:

- During the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368), foreign influence increased. Marco Polo’s travels introduced China to the Western world.

Opium Wars and Unequal Treaties (19th Century):

3. Opium Wars (1839–1842, 1856–1860):

- The Opium Wars, sparked by disputes over trade imbalances and the British opium trade, resulted in China’s defeat. The Treaty of Nanking (1842) ceded Hong Kong and opened several ports to foreign trade.

4. Treaty Ports and Extraterritoriality:

- Subsequent treaties (Treaty of Tianjin, 1856) expanded foreign presence in China through the establishment of treaty ports, extraterritorial rights, and foreign-controlled areas within Chinese cities.

5. Spheres of Influence:

- Foreign powers, including Britain, France, Germany, Russia, and Japan, established spheres of influence in China during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These regions granted exclusive economic and political privileges to the respective foreign powers.

Early 20th Century and World War I:

6. Twenty-One Demands (1915):

- Japan presented the Twenty-One Demands to China during World War I, seeking to further extend its influence in China. While some demands were withdrawn, Japan still gained significant concessions.

7. May Fourth Movement (1919):

- The May Fourth Movement, triggered by the Treaty of Versailles, marked a turning point. Chinese intellectuals and students protested against foreign influence, leading to a surge in nationalism and anti-imperialist sentiments.

World War II and Japanese Occupation:

8. Japanese Invasion (1937–1945):

- During World War II, Japan invaded and occupied large parts of China. The brutal occupation had profound social, economic, and political consequences for China.

Post-World War II:

9. Civil War and Communist Victory (1945–1949):

- After World War II, the Chinese Civil War resumed between the Nationalists (Kuomintang) and the Communists (CCP). The Communists, led by Mao Zedong, emerged victorious in 1949.

10. Formation of the People’s Republic of China (1949):

- The establishment of the People’s Republic of China marked the end of foreign imperialist control, and China began asserting its sovereignty.

Modern Era:

11. Economic Reforms and Foreign Investment (Late 20th Century):

- China’s economic reforms, initiated by Deng Xiaoping in the late 20th century, opened the country to foreign investment. Special Economic Zones attracted international businesses, contributing to China’s economic growth.

12. Hong Kong and Macau Handovers (1997, 1999):

- The handovers of Hong Kong (1997) and Macau (1999) marked the end of foreign colonial rule in these regions, symbolizing China’s assertion of control over its territories.

13. Current Global Economic Influence:

- China has become a major player in the global economy, attracting foreign investment and participating in international trade and diplomacy. The Belt and Road Initiative exemplifies China’s expanding global influence.

Scramble for Concessions

China’s defeats in the so-called Opium Wars brought on the unequal treaty system. Its main features, extraterritoriality and the 5 percent ad valorem tariff, clearly reflected imperialist imposition on China’s integrity and the decline of the Qing dynasty. Still, led by Great Britain, and perhaps best symbolized by Sir Robert Hart and the China Maritime Customs Service, these efforts led to an informal empire, China’s semi-colonial status, and rule, in a way, by missionaries and merchants, defended when necessary by military force.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century the situation changed greatly. In 1884–1885, France easily defeated China and took control of Indochina, a peripheral part of the traditional empire. Matters worsened when, in 1894–1895, Japan equally easily defeated Qing forces and demanded a series of territorial concessions including the island of Formosa, the nearby Pescadore Islands, Korea, and the Liaotung Peninsula in southern Manchuria.

The “triple intervention” in which France and Germany joined with Russia temporarily halted Japanese expansion onto the Asian mainland. Russia demanded a reward for keeping Japan from taking southern Manchuria, and used construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway to gain approval for a shortcut across Manchuria. This shortcut, the Chinese Eastern Railway, saved 1,036 square kilometers (400 square miles) on the 12,949-square-kilometer (5,000-square-mile) trip from Moscow to Vladivostok, and became a vehicle for Russian expansion into Manchuria. Similarly, Germany demanded a concession in eastern Shandong. France also used railway construction to move from Indochina into the Chinese provinces, Yunnan and Guangxi, along the border. Japan sought control over Fujian and Zhejiang provinces that faced Formosa across the Taiwan Straits. And Great Britain, not wanting to lose out as its informal empire gradually collapsed, sought control of Guangdong province adjacent to its leasehold in Hong Kong and Kowloon as well as territory along the lower Yangtze River.

Indeed, many Chinese feared that China would soon go the way of sub-Saharan Africa, and that the Middle Kingdom would disappear from world maps. This hatred of foreign imperialism and the Chinese who, in converting to Christianity, seemed to turn their back on tradition, led to the rise of a secret society, the Righteous and Harmonious Fists, the so-called Boxers that conservative elements of the Qing dynasty encouraged to throw off the foreign yoke. The resulting rebellion surged to Beijing in 1900 and besieged the foreign embassies and the Chinese Christian converts hiding in the legations; a relief expedition advanced to Beijing and rescued the besieged.

For the United States, the scramble for concessions was troubling. After the 1890s depression and America’s new empire after war with Spain and the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands, American business wanted markets for surplus production, and the China market was tempting. The U.S. secretary of state, John Hay, with encouragement from the British government, issued two “Open Door” notes in which he called on the imperial powers not to cut China to pieces and not to incorporate those pieces into mercantile empires closed to American business. Most of the foreign powers ignored Hay, and the situation in China devolved as the Qing dynasty collapsed, and Yuan Shikai seized control and the world moved to World War I (1914–1918). Thereafter, in the 1920s and 1930s, Japan and China began to move down the road to war.

Unit III

Search for New Solutions

Revolution of 1911

The 1911 Revolution was the spontaneous but popular uprising that ended the long reign of the Qing dynasty. It is also known as the Xinhai Revolution, after the Chinese calendar year in which it occurred. The 1911 Revolution had apparently benign origins, beginning with disputes and protests over railway ownership in Sichuan province and surrounding areas. The flashpoint for revolution came in October when a republican-minded army unit mutinied in Wuchang, Hubei province. Their rebellious spirit spread to surrounding regions, igniting a tinderbox of revolutionary sentiment. By the end of 1911, nationalist revolutionaries were assembling to form a new government. These men, led by Sun Yixian, were determined to create a Chinese republic – but they lacked the means to force the Qing to surrender power. In the end, Sun Yixian reached a compromise with powerful military leader Yuan Shikai, whose intervention forced the abdication of infant emperor Puyi. This deal, however, placed power in the hands of Shikai, who was more interested in his own ambitions than furthering Chinese republicanism.